The Delhi High Court verdict awarding life sentence to former Congress leader Sajjan Kumar is definitely welcome but this does not take away the fact that we are far from complete justice. Whenever a political party in power is perceived to be complicit in mass murder and mayhem, justice invariably becomes a casualty. This conviction is an indication of the same malaise. Different yardsticks are adopted for communal violence depending upon political considerations. Justice in this case would have been sweeter if the Modi government had applied the same yardstick to victims of the 2002 Godhra riots. That seems has been relegated to future governments.

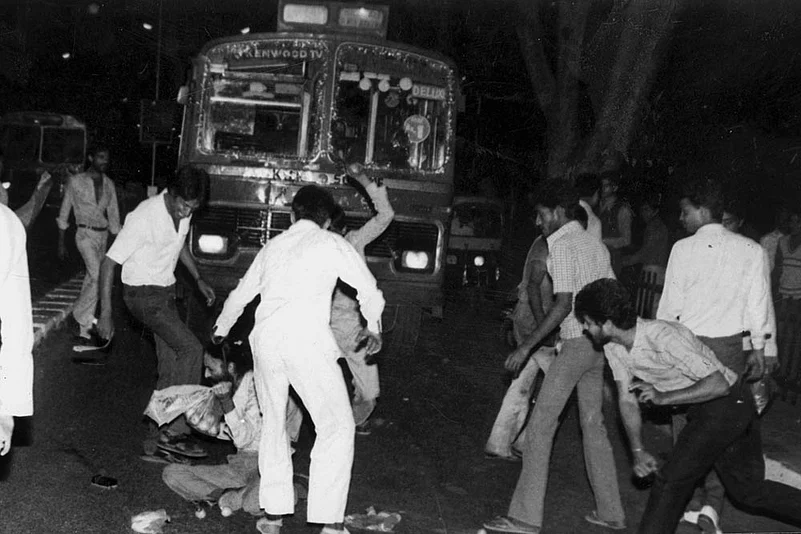

The judgment in this case rests on the testimony of three eyewitnesses—Jagdish Kaur (whose husband, son and three cousins were killed), her cousin Jagsher Singh and her daughter Nirpreet Kaur. The witnesses described how Nirpreet’s father, who was the president of a gurdwara, was burnt to death on the night intervening October 31 and November 1 in 1984. The mob came shouting slogans, and was armed with sticks and rods. The police had taken away the swords from Sikh families earlier. A mob caught hold of Nirpreet’s father and doused him with kerosene. But they did not have a matchbox. A Delhi Police inspector gave the light and told the mob: “Doob maro, tumse ek sardar bhi nahi jalta…(Drown in shame, you can’t even burn a sikh”).

Sajjan Kumar stood in a police vehicle and said: “These were children of snakes and should be killed and burnt.” The mob crushed her husband’s head. Her son was lying on the street. It was on the basis of this evidence that Kumar was found guilty by the high court. To expect honest investigation from the police, which was instigating and abetting the mob, is impossible. Witnesses were kidnapped by the police even from the premises where Justice Ranganath Commission was holding an inquiry. Cops didn’t just refuse to record FIRs but distorted and destroyed evidence. That is why it took nine commissions, seven committees and a Supreme Court-appointed SIT to unearth the truth.

In the face of this evidence, there can be no doubt that this was a rarest of the rare case which deserved the death sentence. Merely because police was equally complicit and prevented any worthwhile investigation resulting in delay of decades can be no ground for sparing capital punishment, which alone could mitigate the pain and restore faith in the hearts of riot survivors.

We still believe in the principle that let a hundred go scot-free but even one innocent must not be punished. Kamal Nath’s case falls in this category. Witnesses Mukhtiar Singh and Mohnish Sanjay Suri have categorically stated that Nath tried to persuade the mob to disperse. The mob of 4,000 retreated for some time. Even police fired several rounds to disperse the mobs on the direction of Nath. It was on the basis of these facts that the Justice Nanavati Commission held that “it would not be proper to come to the conclusion that Nath had in any manner instigated the mob”. We hope the high court judgment may heal some wounds and provide succour to the still-grieving families of the 1984 Sikh massacre.

(The writer is a senior advocate in the Supreme Court and a Member of Parliament in the Rajya Sabha)