A few days after being shortlisted for the Man Booker, which was until this year reserved for writers from countries in the Commonwealth, Indian-American writer Jhumpa Lahiri also made it to the shortlist of the American National Book Award. If she were to win both, The Lowland would become the best book written in the English speaking world in 2013 and Lahiri would be consecrated as the conqueror of this entire territory of English literature. You and I in India will weep with emotion and invoke Tagore and the Bengali legacy. The Americans will grin condescendingly because it is the American Dream to conquer and those who succeed are American by default—call a rose by any name! And for the Brits, who bothers about erstwhile colonisers anymore?

Ever since she won the Pulitzer in 2000, Lahiri is a name that has made me think of a fast-spinning globe. The thought was set off by the legend her book carried: “Stories of Bengal, Boston and Beyond”, the operative word being ‘beyond’. If there was any doubt as to where her fiction was headed, it was dispelled by endless articles and interviews. The breathless media was carving out a magical space for her very realistic fiction: a limen between India and America, not to be found in any old-fashioned atlas but what the spinning globe might throw up as an aspirational image for many Indians. As her publishers proposed and the media disposed, Lahiri has soared beyond geography: she is discussed at the same time as the quintessential Bengali and the South Asian and the American and the postcolonial writer. In fact, an article in a national newspaper put her in the same league as the Bengali writer Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay—so what if she thinks people in Orissa speak Orissi! Only an ungenerous critic would carp about such inessential details or remark on the plethora of fashion-photos of the undeniably comely writer.

When I first came across the epithet “writer of universal themes”, I jumped out of my skin. Hadn’t literary criticism laid the category to rest decades ago on the grounds that demanding universalism from literatures amounts to gagging marginal and contesting voices? But that outmoded kind of Literature with a capital L seems to be back with a bang with the Booker’s plan of embracing the best in English from “Chicago, Sheffield or Shanghai”. The Man Booker is all set to surrender its identity as the bastion of “otherness” and go universal. It was under attack anyway from critics who felt it had been marketing the margins far too flamboyantly and converting every award ceremony into a fashion event by positing exotic show-breakers. Since Rushdie, two Australians, a part Maori, a South African, a woman of Polish descent, an exile from Japan, one Indian and two part-Indians have walked away with the award. And everybody knows that it is only colonials—former and present—who are truly universal.

But these Booker developments might be bad news for the universal Brits. Some critics prophecy an American takeover of the award. The perfect sentence, the amazing syntax, the brilliant image and the exquisite turn of phrase—markers of universality—are, after all, taught much better in their elite creative writing schools that, incidentally, have also mopped up all the postcolonial exotics. Lahiri studied in one and ever since writes melancholically of the assimilation of Bengali immigrants into Bostonian suburbia. Universal writers know about the sad inevitabilities of human existence.

The rest of us who have never been to Boston or fallen out of the universe due to the vertiginous movement of the globe might be better employed appreciating the sterling contribution of the market to literature in these difficult times. Takeovers and conglomerations in the publishing industry have ensured that the responsibility of 90 per cent of global book trade falls on just 3-4 players. Now, such overworked biggies cannot be expected to explore the bylanes of Orissa; the size of their limousines would make it impossible. Besides, where is the time to excavate for writers; don’t they need to concentrate on creating new markets for sheer survival? They are left with the wherewithal to select only 2-3 from those visible when they raise their heads from their desks. Building writers into universal brands again costs a bomb, look at the publicity budgets! After all this, the expectation that their million dollar babies win all the prizes can hardly be considered misplaced. Besides, through the Booker and several such awards aren't they also ensuring the perpetuation of the perfect sentence! Has Literature ever had it this good from commerce?

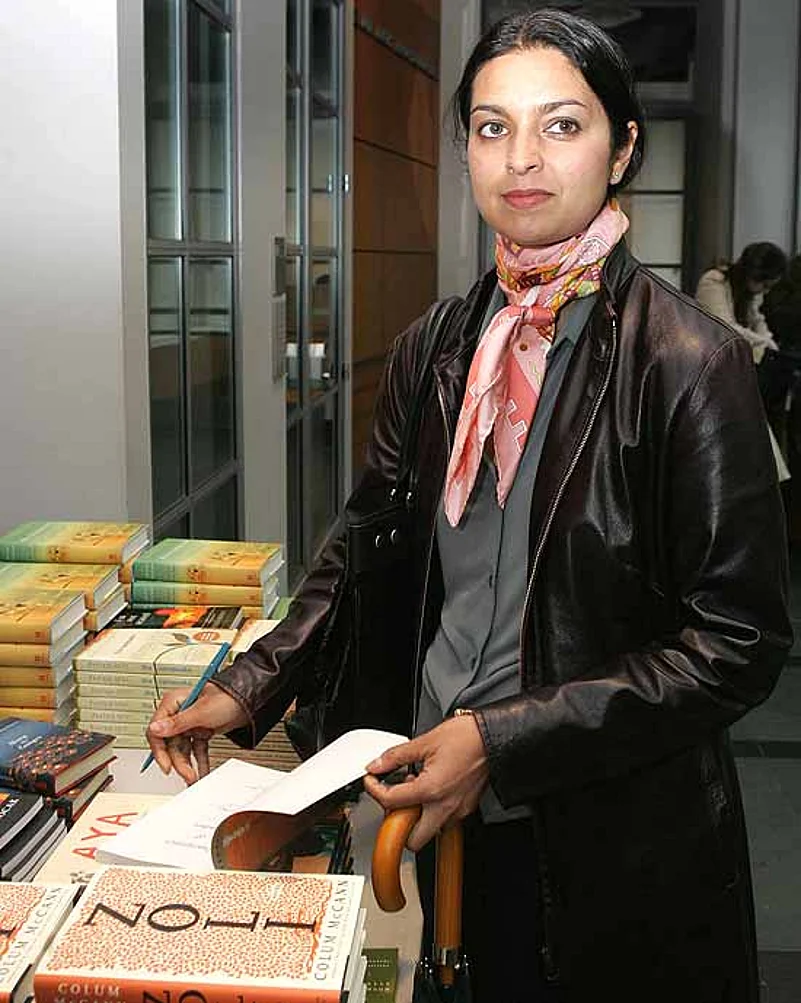

(Anuradha Marwah is an author and academic)