The UPA’s proposed land acquisition, rehabilitation and resettlement (LARR) bill contains several provisions which seek to improve upon the existing land acquisition law. Anyway, the present law has clearly run its course, with people no longer willing to submit to coercion by the state. The enactment of a new land acquisition law, in order to make it congruent with a democratic state, is long overdue. Whether it would be possible for the UPA-II government to ensure the passage of the LARR bill, given the delay already caused, remains to be seen.

The LARR bill attempts to bring changes in three aspects of the land acquisition process: (a) providing more clarity on the definition of ‘public purpose’ for which land can be acquired by the state, (b) conducting a social cost-benefit analysis before deciding on acquisition and seeking the opinion of affected persons and (c) integrating rehabilitation and resettlement with the acquisition process, setting concrete benchmarks for compensation. But the current provisions of the bill fall short of expectations in all three counts.

While defining ‘public purpose’, the LARR bill distinguishes between public sector projects and private sector/PPPs. For the latter, the consent of at least 80 per cent of affected persons will be required before acquisition, but for public sector projects land can be acquired without any prior consent. Besides, a wide range of projects in the public sector—railways, highways, ports, power, mining, pipelines, irrigation, even SEZs etc—have been exempted from all of the bill’s provisions. Thus the LARR bill will make no difference to a substantial proportion of land acquisition.

Such exemptions for public sector projects are unjustifiable. For a small adivasi farmer whose land is being acquired for a power plant or a mining project, the consequences of displacement remain the same, whether it’s under the public or the private sector. Unless prior consent of affected people applies to all cases of acquisition, the bill’s provisions will be misused and the purpose of the legislation defeated.

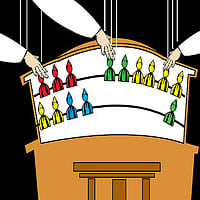

Under the provisions of the LARR bill, a social impact assessment has to be mandatorily conducted by the government in all cases of acquisition in consultation with the gram sabha (or a comparable urban body) and appraised by an independent panel. However, the final decision-making power lies with the bureaucracy. And the structure of accountability tying it to the affected persons or their elected representatives is weak. The corrosive influence of vested interests in the acquisition process can’t be checked unless decision-making powers are further devolved and decision-making subjected to strict accountability. Penal provisions against corrupt officials who violate or manipulate the law to coerce/cheat owners must be made more stringent.

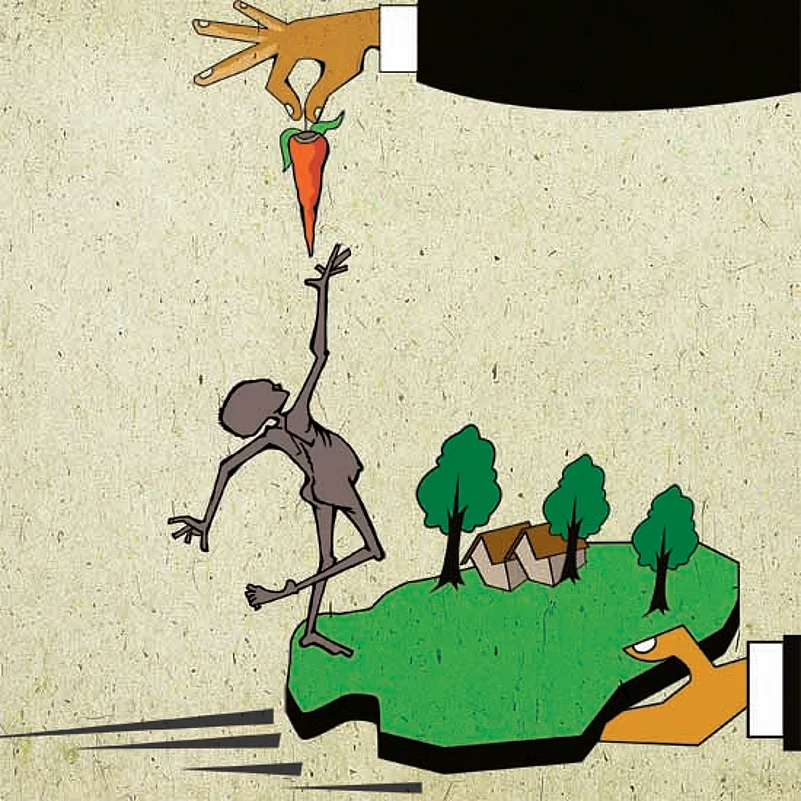

At the heart of the opposition to compulsory land acquisition lies the consequences of displacement on the livelihoods of the poor. In its preamble, the LARR bill promises to ensure that “the cumulative outcome of compulsory acquisition should be that affected persons become partners in development, leading to an improvement in their post-acquisition social and economic status”. This is important, which, if properly enshrined in the law and implemented on the ground, can resolve much of the current conflict. An important step towards that is to make it mandatory for all projects involving acquisition to provide jobs to one member of each affected family. The LARR bill stops short of this and makes the provision for employment to affected persons as one among other options, like an annuity for twenty years or a one-time compensation of five lakh rupees per family.

Unemployment—often disguised—is the biggest curse affecting our society, especially in rural areas. Even with a growing GDP, joblessness is acute. In such a backdrop, is it fair to expect a small farmer to part with his small piece of land for a development project unless the security of his livelihood is guaranteed by that project? The responsibility of upgrading skills of the affected to the level required to ensure employability in that project should lie with the acquirer of land. There will be no end to conflict over land acquisition unless this issue is addressed squarely.

As far as monetary compensation is concerned, the formula proposed in the LARR bill—to fix the amount at four times the ‘market value’ in the rural areas and twice that amount in the urban areas—is far from ‘scientific’. Given the ground realities, any calculation of ‘market value’ based on sale deeds will be misleading. These can at best serve as floor values, based on which the affected persons are allowed to negotiate a ‘market value’ which appears fair to them, in a coercion-free environment. If the purpose is to make affected people ‘partners’ in the development, such a mechanism needs to be institutionalised. For that we have to collectively get rid of the mindset of making ‘land available for cheap’, in a land-scarce country like ours.