It may not have registered on the Richter scale of urban mediascape, but the 48-hour truce preceding the release of Malkangiri collector R. Vineel Krishna on February 24, and five Chhattisgarh policemen on February 11, by their Maoist abductors was palpable in the rebel-held areas. No combing by the police or the paramilitary, no armed action by the Maoists. In Chhattisgarh’s case, the significance of the truce found expression in chief minister Raman Singh’s comment at a joint press conference with Swami Agnivesh and other rights activists who had secured the policemen’s release: “Why can’t this truce continue beyond this incident and Maoist issues resolved through talks with help from such mediators?” It’s another thing that his government restrained the freedom of one such possible mediator, Binayak Sen, a couple of years ago and continues doing so. It’s also another thing that there was no follow-up on Singh’s thinking aloud. After his release, collector Krishna, too, made some interesting observations: he said time spent among poor tribals in Maoist areas had made him more sensitive to their troubles and that there could always be a debate on different development perspectives. But in this case too, we see no immediate prospect of a “sensitive” state reaching out for a debate with those who have taken up arms for a “different development” perspective.

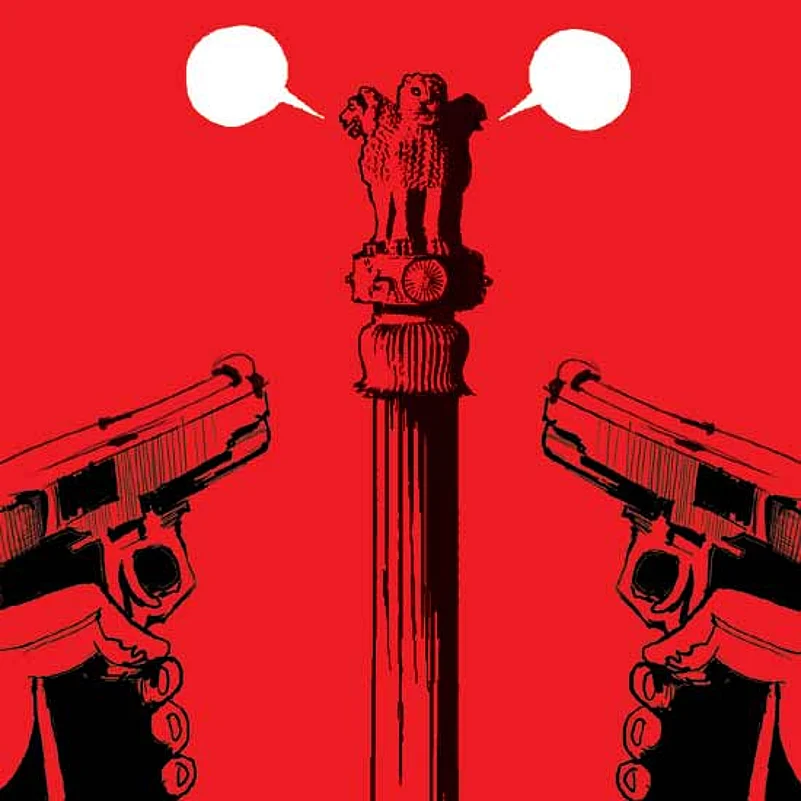

Why does the state show an eagerness to negotiate with its alienated citizens only when armed groups constrain and endanger members of the ruling elite? This exposes the hierarchical impulses of a state which treats the lives of people lower down the ladder, whether its own employees or ordinary citizens, as mere cannon fodder. Contrast the swift extra effort made by Orissa to meet Maoist demands for the release of an IAS officer and the ten-day-long spell of indifference by Chhattisgarh towards Maoist conditions for the release of ordinary police constables, who were released by their abductors in response to appeals from rights groups. Instead of talking in an ad-hoc fashion on specific rebel demands when forced to do so, why can’t the state make a gesture to its alienated people, often victims of state policy, unconditionally and have a comprehensive strategy for engagement and negotiation under a framework of natural justice? Some uninformed commentary in the media recently suggested that the Chhattisgarh and Orissa abductions mark a tactical change by besieged Maoists, who are now taking recourse to kidnappings to force the government to release their comrades and meet their other demands. In fact, Maoists have carried out kidnappings a number of times as tactical manoeuvres or as political statements. More spectacular than even the Malkangiri collector’s kidnapping was the abduction of 11 government officials, including seven IAS officers, by Maoists in the Gurthedu forests of Andhra Pradesh in 1987. It was the late K.G. Kannabiran, an eminent rights activist and lawyer, who had negotiated their release. In May 1991, he again negotiated with the Maoists for the release of Congress MLA P. Sudhir Kumar, son of then Union minister P. Shivshankar. And in 1993, he secured the release of Congress MLA P. Balaraju (now a minister in Andhra Pradesh), IAS officer D. Srinivasulu, and four engineers. It’s a pity that the openings for negotiation provided by those incidents were never followed up with a comprehensive peace process; the temptation for an armed solution probably weighs more with governments. The negotiation process could certainly have been built upon, from those beginnings, but that was not to be.

In the 2000s too, Kannabiran, S.R. Sankaran (a former IAS officer, one of the seven abducted by the Maoists in 1987), Prof G. Hargopal (one of the mediators in the Malkangiri abduction saga) and their friends worked to bring left extremists and the Andhra government to the negotiation table. But these efforts came to naught because of mutual mistrust and the government’s impatience. Both Kannabiran and Sankaran died recently, disappointed men of peace.

Meanwhile, the Maoists have made a telling political statement with the recent abductions and release: they did not ask for the release of their top politburo leaders who are in jail but asked for the release of other cadre, including women, and made demands of interest to their tribal constituency. They also released ordinary constables unconditionally, for whom the state didn’t show as much eagerness to negotiate as for IAS officer Vineel Krishna, though we must concede that he certainly is a sensitive, pro-poor face of the state he serves. It’s a face that the whole state and all its administration must show. Always.