I am taking a ride in the Calcutta Metro a month before its 25th anniversary. It is the first day of the Durga Puja festivities, a tremendous pulse of energy and colour that electrifies the metropolis each year. The train is full to the brim. Vehicular traffic is severely restricted on Puja days to accommodate the millions of revellers on foot. So, everyone prefers the Metro. Around me are Calcuttans from all walks of life, resplendent in Puja finery. The car is abuzz with laughter, anticipation, rustling new cotton and jingling jewellery. I am riding end to end, from the Kavi Nazrul station in the deep southern suburbs to Dum Dum in the far north, all 22 km of Calcutta Metro’s sole line along the city’s north-south axis.

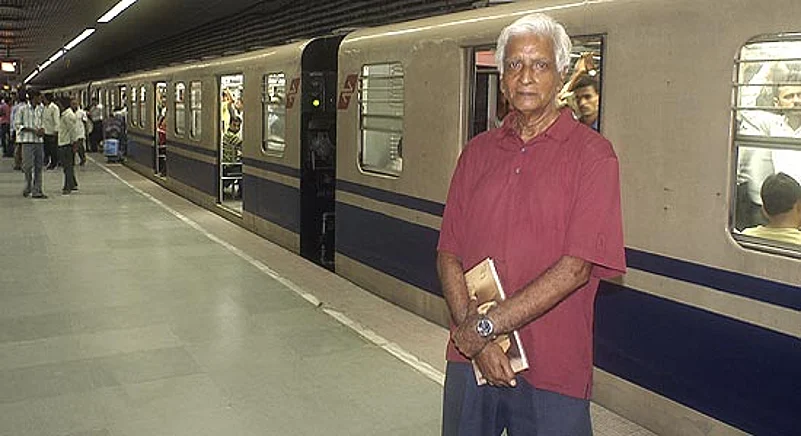

Main man: Ashok Sengupta, chief engineer of the Calcutta Metro in 1984

Riding with me is Ashok Sengupta, the chief engineer of Calcutta Metro when it opened its doors on October 24, 1984. Sengupta is 77, but holds his tall frame ramrod straight. My Metro ride is very different from his Metro ride. I watch him engage with his life’s work and watch him watch the Puja crowd enjoy it. To stand next to him is to confront the reality that nothing I will ever build will be remotely as satisfying.

The 5 km of track between Kavi Nazrul and Tollygunge is elevated through Calcutta’s south suburban sprawl; this section was opened in August 2009. The remaining 17 km between Tollygunge and Dum Dum runs underground and was opened in phases until its completion in 1995. A 4 km section of this, spanning the city’s dense central core between Bhawanipur and Esplanade, was inaugurated in 1984. The Calcutta Metro has a small footprint relative to the city’s size. But it is intensely loved, serving 5 lakh riders daily. The love came later. First, there was rage.

I can recall this rage with clarity. Calcutta’s moist earth and high water table meant that barring a 1.2 km tunnel, the entire construction was cut-and-cover. This open cut ran along Calcutta’s chief north-south arterial, consuming, in some places, over half the carriageway. I have dystopian memories of Central Avenue, along the frenetic central business district: it was a river of sludge dotted with rusty steel girders, with two narrow strips on either side for buses, cars, trucks and hapless pedestrians to share. This disruption lasted through the ’80s and into the ’90s. For most of my youth, Calcutta bore a vast oozing gash along her spine: the Metro gash.

As we head north past Tollygunge the train descends underground, and Sengupta shares a dig story. The Metro cut near Rabindra Sarobar went under a railway bridge. One evening he got a frantic call from the foreman: cracks had appeared on a supporting pillar of the bridge, a crucial link between Sealdah station and west Calcutta. Losing it would put the final nail in the Metro coffin, further enraging an irate public, an impatient state, and an overspent Centre. Sengupta says, “I pictured myself as Casabianca”. He was going to stand on the burning deck.

He alerted Sealdah asking them to hold up the trains. He marshalled his workers to start the grouting: water had pooled in the cut, they added cement to firm it. Meanwhile, a large backlog of trains had piled up. He decided to personally ferry the trains across the bridge. He notified Sealdah to restart traffic, but asked that the trains stop at the bridge. For each train, he got in the driver’s cabin and stood next to the driver as he gingerly drove to the other side.

He did this deep into the night for over a dozen trains. He believed the grouting would hold before the cracks spread, but there was a non-zero risk. His collateral for this risk was himself. The bridge held then and holds to this day. That defining night from over a quarter century ago briefly descends around Sengupta as he relates this story. We arrive at Esplanade where a cloud of Puja revellers board the train, blissfully unaware, as most of us are, of the stories of how a nation is built.

We soon head north under Central Avenue. This section took the longest to finish; by then I had left the country. Back in Calcutta on a visit in 1996, after having ridden the metro systems in New York and San Francisco, I remember being stunned by my first Calcutta Metro ride. The new trains were spare but shockingly on-time; the stations were spotless, the fares absurdly cheap.

But most astonishing of all was the Metro’s effect on the riders. The same man who spit out a large gob of phlegm before entering the Metro station would keep all his bodily fluids strictly to himself during the ride. The man who would think nothing of fondling a schoolgirl in a bus would abandon the thought while underground. Could it be that a civil setting forces a man into civil behaviour, and civil behaviour in turn ensures the setting remains civil?

As we approach Dum Dum, Sengupta describes his generation’s passion for indigenous engineering. From design to implementation, from the rakes to the smallest nuts, the Metro project was Indian; its workers felt a keen sense of ownership. He understands that, 25 years on, the Delhi Metro project is being conducted very differently. As the nation’s first, Calcutta Metro has valuable lessons to offer. Even if some are, as many parents learn from their first-born, lessons in what not to do.

The Metro gash has long healed. It’s Durga Puja. The Metro will run all night on all four nights. A grateful and bedecked Calcutta will surge aboard.

(Rimli Sengupta is a Calcutta-based writer with a Phd in engineering.)