It means well, but fails to do justice to its subject. A new exhibition at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies is an ambitious but flawed attempt to understand Zoroastrianism, which claims to be the world’s first monotheistic faith and the state religion of the first global superpower, ancient Persia. Both claims are shrouded in antiquity, but deeply embedded in the psyche of India’s tiniest and most successful minority, the Parsis.

Sometimes called ‘the Jews of the East’, the Parsis too have a history of a very creative diaspora. Having migrated from Persia to Gujarat during the 8th to 10th centuries AD, one of their founding myths in India was that they were refugees from Muslim persecution after the Arab conquest of Zoroastrian Persia. But historical evidence shows that their migrations were motivated as much by trade as by religious dissent.

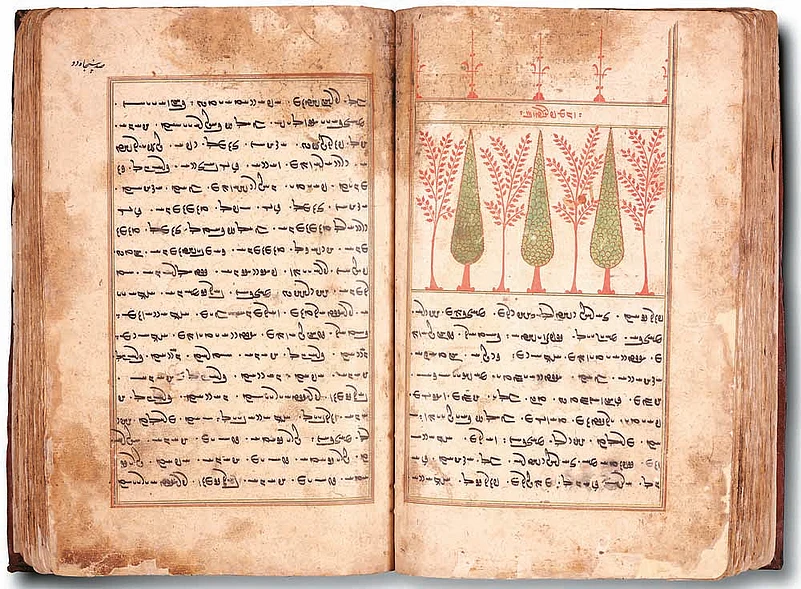

A frieze on a brass bowl

The London exhibition, with its lack of any narrative structure, sheds little light on such questions. Nor does it define the role of Zoroastrianism in Persia’s mighty Achaemenid Empire, which ruled most of the known world at its peak in the 5th century BC. The first imperial inscriptions honour Ahura Mazda, the Zoroastrian Lord of Light, as the chief deity in a land which also worshipped pagan gods and goddesses, similar to those of their Vedic Hindu contemporaries. One has no sense in this exhibition, with its small and dingy spaces and unreadable labels, of the majestic friezes and colonnades of Persepolis and Susa, with their giant winged bulls symbolising Achaemenid global dominance. The tawdry attempt at creating a walk-in replica of a Bombay fire-temple lacks the solemnity or tranquility of the real thing.

An ewer

The existence of the prophet Zoroaster (Zarathustra), unlike that of Christ and Mohammed, is undocumented, resting solely on oral traditions that date him to prehistoric times. But that doesn’t prevent his followers from depicting him visually as a Christ-like figure with a flowing beard and robes. Such portraits apart, the Parsis are iconoclasts: only the sacred flame, burning at the heart of their temples, symbolises the presence of Ahura Mazda. The thrust of the religion is abstract, ethical: good thoughts, good words, good deeds.

An ossuary

Growing up in India in the 1950s as the child of a then very rare Parsi-Hindu love match, I was acutely conscious that the Parsi sense of ethical superiority was closely linked with a mythical belief in their racial purity. Despite obvious visual evidence of inter-marriage with Gujaratis, there was a tacit faith in the superiority of the ideal Parsi type: fair-skinned, even blue-eyed, with aquiline noses. My grandmother closely fitted that ideal, and I still remember her scrubbing me in the bath in a vain attempt to lighten my brown, Hindu colouring.

A Tanchoi sari

Perhaps it was that sense of ethical and ethnic distinction that first drew the Parsis closer than any other Indian community to the British colonial rulers. Despite their tiny numbers—1,00,000 in a subcontinent of 600 million—the Parsis dominated the upper echelons of the Raj, excelling at everything from industry and banking to science, education and the arts. There were obvious parallels with the success of the Jews in pre-wwii Europe; but Parsis have so far escaped any racist backlash. The credit must go partly to Indian traditions of tolerance and partly to a peculiarly Parsi sense of bonhomie, which made even their racial exclusivity seem more idiosyncratic than offensive. Other Indians, and Parsis themselves, like to joke about the lovable eccentricity, sometimes sheer lunacy, of Parsi families shaped by centuries of inbreeding.

D.J. Tata

The London exhibition offers little sense of how well the Parsis have assimilated into Indian life. The most telling example might have been Parsi cuisine, with its unique blend of sweet Persian fruit and nut flavours with more fiery Indian spices. But exhibitions have to make do with artefacts; and the most beautiful on display here are the embroidered Gara silks and Tanchoi brocades which the Parsis imported into India as part of their booming 19th century trade with China. It was typical of the pragmatism of Bombay’s Parsi merchant princes that they made their fortunes selling opium to the Chinese, but spent much of those profits endowing the philanthropic and educational trusts for which they are renowned, and from which many non-Parsi Indians still benefit.

(The Everlasting Flame: Zoroastrianism in History and Imagination is at the Brunei Gallery, School of Oriental and African studies, London University)