Narendra Modi’s gobsmacking victory may make the nation sit up and see the Gujaratis as a little more than khakda, commerce and ‘A/C video coach tour with own cook’. We Parsis and the Gujaratis, like the English and the Americans, are two peoples divided by a common language. I’ve been surrounded by them all my life. Does that mean I’ve decoded the Gujarati character? Naa baapa, it’s a community as complex as an Amit Shah electoral strategy.

I grew up with Gujaratis. This was not in our home base of western India, but across the subcontinental breadth, in Calcutta. The Parsis then and there, as always and everywhere, were minuscule in number compared to the Gujaratis, but we did assert ourselves in two ways. One, with the single play in Gujarati produced every Parsi New Year by the Calcutta Parsi Amateur Dramatic Club. In a more sustained relationship, they subscribed to the weekly Navroz, which proclaimed from its masthead that it was ‘Eastern India’s only Gujarati journal’. It was established by my grandfather in 1917, and later edited by both my parents. Deferring wisely to its larger reader (and advertiser) base, the Navroz bumper annual was not on our own Pateti, but on Diwali.

As a family, this link with the Gujaratis and their institutions became more personalised by the fact that the 100-year-old mansion housing both our home and the press was deep within one of the city’s two Gujarati enclaves. In the packed buildings of the warren around our Ezra street, their community lived, worked, and went to the Calcutta Anglo-Gujarati School, where my grandmother had pioneered the education of its girls.

With none of my school friends in the vicinity, I went over to play with Bhanu Thacker, and at least once a week and most willingly sat cross-legged on the kitchen floor as her mother, Kantaben, plonked steaming, ghee-laced khichdi on to our thalis. The Thackers were my first, if subconscious, study of one of the most distinctive drivers of the Gujarati community: its imperative of upward mobility. As the family dealership in edible oils flourished, Bhanu’s youngest brother was sent to Hindi High School instead of the local Gujarati one. And his progressive father sent him over to our house for ‘omlets’. It was small exchange for all those weekly dinners, the doodhpak and home-made Diwali goodies.

From that first exposure came another insight into the unselfconscious expression of the Gujarati spirit. Stuck in the city’s manic traffic inside the Thackers’ new Ambassador, Bhanu impatiently fretted, “Even though we have a ‘private’, we have to suffer these jams.”

The community’s best-known DNA drove the commerce of nearby Mehta building, chock-a-block with tiny trading shops for electricals and pharma. But there was also Meghani the publisher, and the writers and poets who contributed essays and stories to the Navroz and became friends with my mother, whose literary Gujarati rivalled their own because she had grown up in Navsari, and studied in that language as well as in Persian unlike my Calcutta-Xavierite father. It wasn’t just our own Shiv Kumar Joshi with his crisp khadi kurtas and distinctive shock of silvering hair or the enfant terrible poet, Madhu Rye. The Gujarati literary greats who sent in their pieces to our Diwali annual established in my still-pliant mind the fact that ‘dhandho’ is not the only Gujarati deity nor ‘rokda’ its only royalty.

Leaving that close-knit outpost and plunging into Bombay’s omnipresent community ironically depersonalised my old link with the Gujaratis. Wandering homesick through the community concentration around Bhuleshwar, I was in real danger of succumbing to the ‘only dhando’ stereotype, even though ‘only Dhirubhai’ was yet to stamp himself like a later Antilia on the city’s mental skyline.

Then Ahmedabad became my ‘town-in-law’, and over the next four decades I was exposed through a wider aperture to the complex, often conflicting, Gujarati ‘character’. If Gujarat was the experimental theatre of Hindutva in those rath-driven days, it was even more the experimental theatre of food. Proof of this lay in the ‘veg burger’ with amli-ni-chatni, the ice-cream in every inconceivable flavour, syrup and topping at the iconic ‘Chills, Frills, Thrills’ (which arguably outrivalled ‘New Yorker’, the over-the-top teerthdham of Mumbai’s Gujju salivation seeker). In fact, these were symbols of a wider adventurism, often uninhibited by the spoilsport restraints of sophistication. If pepperoni pizzas fell like dominos in Navrangpura a full decade before the ‘Jainification’ of Mumbai’s Malabar Hill, it was because an economically influential community could assert its domination on the larger taste. And did so with unabashed aggression.

Part of the same narrative was the aroma of theplas pervading deodorised Swissair cabins and Europe’s (or Nepal’s) hills coming alive to the sound of ‘Kem, Kanubhai, tamey pun Raj Travels ni pure vaij tour par avya?’ Clearly, long before Bunty and Babli, and today’s HMT time—the storming of the high table by ‘Hindi Medium Types’—the Gujaratis of Ahmedabad had pitched their tents on these cultural frontiers.

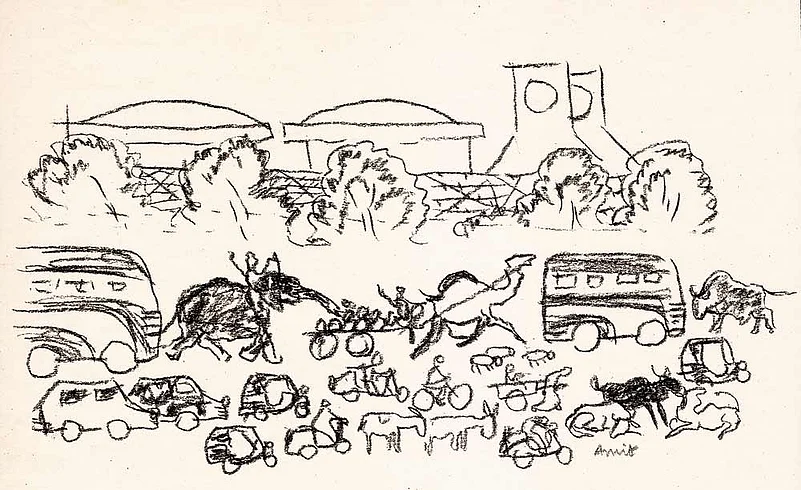

So can I say that this often-crass adventurism was and is the dominant chromosome of the Gujarati culture? How could it be in the presence of the old mill-maliks and the institutions they built which had so elevated this city? The Kasturbhai Lalbhais, the Sarabhais, and as much the ‘Sarabens’, Mrinalini and Mallika. There was the architect Balkrishna Doshi, the artist Amit Ambalal. Nearby Baroda was the home to the eponymous art school and the homoerotic canvases of Bhupen Khakhar, even if in 1998 M.F. Husain’s paintings were vandalised at its university named after Sayaji Rao, the Gaekwad who exemplified Gujarat’s most enlightened graces.

And what about the Gujaratis who had exemplified non-violence as both ideology and an imperative for the uninterrupted conduct of commerce, but who in 2002 also massacred with a savagery as unbelievable as it was unconscionable.

My most recent Gujarati connection is the one closest to home, literally if not physically. Son No. 1 married a girl who, in the enviable classification of Ramachandra Guha, is an ‘abcdefg’, American Born Confused Desi Emigrated From Gujarat. Anisha is by no means confused; her father emigrated via Uganda, and is not a Motel-Patel but a highly regarded civil engineer working for the US army while her mother runs a cool boutique on historic Savannah’s riverfront.

So now I know I’m cued into the other, equally dominant Gujarati ‘type’. Global in its geography, sipping Cosmopolitans with elan, but still encompassed by the clan. This too is of a piece with my own ‘in-law’ Ahmedabad, where the upwardly mobile moved away from the maze of ‘pols’ to futuristic housing complexes across the river, but established in each of these soaring towers an exclusive stronghold of their own Lohana, Kansara, Kutchhi-Bhatia sub-community.

The untrammelled adventurer into lands unknown and food unforgivable? The single-minded, all-else-excluding pursuer of profits? The patron of education and the arts? The astute, unscrupulous politician? The abandoned dandiya dancer? The sattvik ascetic? Gandhi or a Maya Kodnani? Will the real Gujarati please stand up?

And one attendant thing: if the real Modi is not the statesman of his latter-day manifestation, will that facet of him please remain seated, indeed submerged.