Hopes that Pakistan might abandon its policy of supporting jehadis with its right hand even as it slaps them with the left died shortly after the killing of Osama bin Laden by the US navy’s seals in Abbottabad. The world’s most prized fugitive was discovered ensconced in a mansion close to the famed Kakul Military Academy. But in spite of what columnist Ayaz Amir called the “mother of all embarrassments”, introspection and remorse were noticeably absent at the corps commanders’ conference three days later. Bluster dominated: the US would get a befitting response should it again violate Pakistan’s territorial integrity through “unilateral military action”.

The civilian government quaked as all this unfolded. It dared not suggest that the military was responsible for the putative intelligence failure. Tongue-tied for 36 hours, it awaited pointers from the army and then dutifully followed them. But the army was not satisfied; it wanted a proactive defence from the government. Gen Ashfaq Parvez Kayani made clear his unhappiness: “Incomplete information and lack of technical details have resulted in speculation and misreporting. Public despondency has also been aggravated due to an insufficient formal response.”

Thus prodded, a full eight days later, Prime Minister Yousaf Raza Gilani broke his eerie silence, absolving the army and the ISI of “either complicity or incompetence”. Before an incredulous world, he claimed both charges were “absurd”. And in a desperate attempt to spread the blame, he declared, “This is an intelligence failure of the whole world, not Pakistan alone.” In mutually contradictory statements, the government condemned the assassination while also claiming that the operation was carried out “in accordance with declared US policy that Osama bin Laden will be eliminated...wherever found in the world”, and that his death is a “setback to terrorist organisations around the world”.

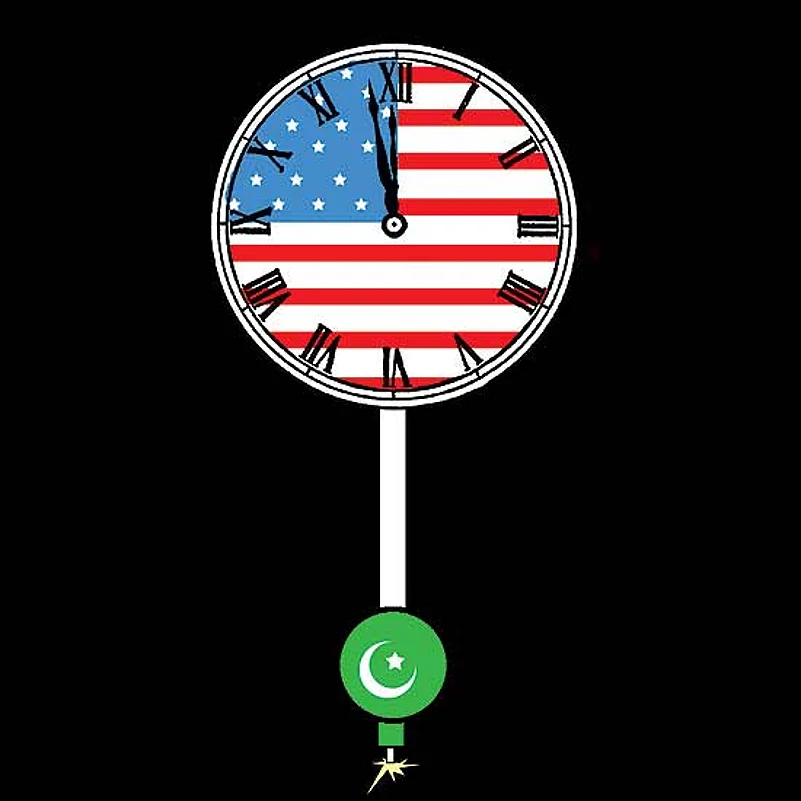

The future? Though epoch-making, Osama’s assassination will have astonishingly little impact on Pakistan, or even on US-Pakistan relations. Angry US congressmen have accused Pakistan of double-dealing, and moved a bill to cut off all aid. This is unlikely to pass. Osama’s fortuitous elimination gives the US good cover to cut and run from an unsustainable war in Afghanistan. But until the US largely withdraws—which will certainly not happen before 2014—it will remain beholden to Pakistan for allowing nato supplies to be trucked across its territory as well as for limiting the operations of the Haqqani network (run by Maulvi Jalaluddin Haqqani and his son Sirajuddin, and allied to the Taliban) in North Waziristan. Even more importantly, it is nervous about Pakistan’s ever-expanding nuclear arsenal and does not want its working military-to-military relationship to end.

Pakistan has its own reasons to avoid a divorce. Its economy is dependent upon US largesse and could otherwise rapidly collapse. It also sees strategic depth in Afghanistan once again lying within the realm of possibility, but this requires US acquiescence. All things considered, neither side feels it can afford to really upset the apple cart.

The Pak-India balance will also remain stable. Abbottabad might inspire some Indians to dream about Muridke and Bahawalpur, where the Lashkar and Jaish have HQs. But Indians know that, should they engage in an Abbottabad-like mission, the Pakistani response would be different—and disproportionate. Where nuclear-tipped missiles are poised for flight across borders, it is wise to avoid such fatal fantasies.

One need only recall Operation Parakram, India’s response to the December 2001 attack on its Parliament. It saw India mobilise nearly half a million soldiers along the LoC to punish Pakistan for harbouring Jaish, which had initially claimed responsibility for the attack. When Parakram fizzled out, Pakistan claimed victory and India was left licking its wounds.

Thus, New Delhi is unlikely to emerge with major gains. Its major demand—the crushing of anti-India militant groups on Pakistani soil—will not be fulfilled in the immediate aftermath. Pakistan’s strategic culture remains predicated on countering India. Maintaining, expanding and upgrading Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal to offset India’s growing military strength will therefore remain key to maintaining balance. Frankly, India should blame no one but itself for having aggressively initiated the nuclearisation of South Asia, in which the ultimate winner has been Pakistan.

Pakistan’s generals are red-faced today, but they are practised survivors. Secretly sending militants and soldiers across the LoC in Kargil, profiting from A.Q. Khan’s sale of nuclear wares and giving tacit permission to the Lashkar’s operations—none of this proved fatal when discovered. They will surely survive this crisis as well. For Pakistan’s people, it shall be business as usual. Unfortunately.

(The writer, a physics professor, teaches in Islamabad & Lahore.)