“Patriotism,” Samuel Johnson said nearly 250 years ago, “is the last refuge of a scoundrel.” These days in India, the adage can be safely applied to nationalism. There is no other explanation of the threat to arrest and try Arundhati Roy on charges of sedition for what she said at a public meeting on Kashmir, where Syed Ali Geelani too spoke. I was not there at the meeting, but I have read her moving statement defending herself afterwards. I feel both proud and humbled by it. I am a psychologist and political analyst, handicapped by my vocation; I could not have put the case against censorship so starkly and elegantly. What she has said is simultaneously a plea for a more democratic India and a more humane future for Indians.

I faced a similar situation a couple of years ago, when I wrote a column in the Times of India on the long-term cultural consequences of the anti-Muslim pogrom in 2002. It was a sharp attack on Gujarat’s changing middle-class culture. I was served summons for inciting communal hatred. I had to take anticipatory bail from the Supreme Court and get the police summons quashed. The case, however, goes on, even though the Supreme Court, while granting me anticipatory bail, said it found nothing objectionable in the article. The editor of the Ahmedabad edition of the Times of India was less fortunate. He was charged with sedition.

I shall be surprised if the charges of sedition against Arundhati are taken to their logical conclusion. Geelani is already facing more than a hundred cases of sedition, so one more probably won’t make a difference to him. Indeed, the government may fall back on time-tested traditions and negotiate with recalcitrant opponents through income-tax laws. People never fully trusted the income-tax officials; now they will distrust them the way they distrust the CBI.

In the meanwhile, we have made fools of ourselves in front of the whole world. All this because some protesters demonstrated at the meeting that Arundhati and Geelani addressed! Yet, I hear from those who were present at the meeting that Geelani did not once utter the word “secession”, and even went so far as to give a soft definition of azadi. By all accounts, he put forward a rather moderate agenda. Was it his way of sending a message to the government of India? How much of it was cold-blooded public relations, how much a clever play with political possibilities in Kashmir?

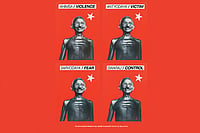

We shall never know, just because most of those who pass as politicians today and our knowledge-proof babus have proved themselves incapable of understanding the subtleties of public communication. They are not literate enough to know what role free speech and free press play in an open society, not only in keeping the society open but also in serious statecraft. In the meanwhile, it has become dangerous to demand a more compassionate and humane society, for that has come to mean a serious criticism of contemporary India and those who run it. Such criticism is being redefined as anti-national and divisive. In the case of Arundhati, it is of course the BJP that is setting the pace of public debate and pleading for censorship. But I must hasten to add that the Congress looks unwilling to lose the race. It seems keen to prove that it is more nationalist than the BJP.

It is the hearts and minds of the new middle class—those who have come up in the last two decades from almost nowhere and are middle class by virtue of having money rather than middle-class values—that both parties are after. This new middle class wants to give meaning to their hollow life through a violent, nineteenth-century version of European-style ‘nationalism’. They want to prove—to others as well as to themselves—that they have a stake in the system, that they have arrived. They are afraid that the slightest erosion in the legitimacy of their particularly nasty version of nationalism will jeopardise their new-found social status and political clout. They are willing to fight to the last Indian for the glory of Mother India as long as they themselves are not conscripted to do so and they can see, safely and comfortably in their drawing rooms, Indian nationalism unfolding the way a violent Bombay film unfolds on their television screens.

Hence the bitterness and intolerance, not only towards Arundhati Roy, but also towards all other spoilsports who defy the mainstream imagination of India and its nationalism. Even Gandhians fighting for their cause non-violently are not spared. Himangshu Kumar’s ashram at Dantewada has been destroyed not by the Maoists but by the police. I would have thought that writers and artists would be exempt from censorship in an open society. As we well know, they are not. The CPI(M) and the Congress ganged up to shut up Taslima Nasreen by saying she was not an Indian. As though if you are a non-Indian in India, your rights don’t have to be governed by the Constitution of India!

The trend of harassing political dissenters for their “seditious” writings and actions started early. It started with the breakdown of consensus on national interest in the mid-’70s. Indira Gandhi imposed Emergency and introduced serious censorship and surveillance, she claimed, to protect national interest, democracy and development. (She had foresight, for though she included development in her list, it took another two decades for the consensus on development to break down.) The difference between the 1970s and the first decade of the 21st century is that millions are now acting out their dissent and speaking out of their radical differences with mainstream public opinion. The whole tribal movement—wrongly called the Naxal movement, because the Naxals have taken advantage of the tribal problem—is an example of this.

There are times when a national consensus is neither possible nor desirable. The best one can do is to contain the violence and negotiate with those who act out their dissent. That may not be easy in the case of the Kashmiris because their trust in us is now close to zero. Psychologically speaking, the Kashmiris are already outside India and will remain there for at least two generations. The random killings, rapes, torture and the other innovative atrocities have brutalised their society and turned them into a traumatised lot. If you think this is too harsh, read between the lines of psychotherapist Shobhna Sonpar’s report on Kashmir.

What is it about the culture of Indian politics today that it allows us to opt for a version of nationalism that is so brutal, self-certain and chauvinist? Have we been so brutalised ourselves that we have become totally numb to the suffering around us? What is this concept of Indian unity that forces us to support police atrocities and torture? How can a democratic government, knowing fully what its police, paramilitary and army is capable of doing, resist signing the international covenant on torture? How can we, sixty years after independence, countenance encounter deaths? Could these practices have survived so long and become institutionalised if we had a large enough section of India’s much-vaunted middle class fully sensitive to the demands of democracy?

The answers to these questions are not pleasant. We know things could not have come to this pass if those who are or should be alert to these issues in the intelligentsia, media, artistic community had done their job. Here I think the changing nature of the Indian middle class has not been a help.

We are proud of our democracy—the consensus on democracy still survives in India—but unaware of a crucial paradox in which we are caught. The democratic process has created a new middle class, a large section of which is not adequately socialised to democratic norms in sectors not vital to the survival of democratic politics but vital to creativity and innovativeness in an open society. The thoughtless, non-self-critical ultra-nationalism, intolerant of anyone opposed to the mainstream public opinion, is shared neither by the poor nor the more settled middle class. Ordinary Indians, accustomed as they are to living with mind-boggling diversity, social and cultural, have no problem with political diversity. Neither does the settled middle class.

Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, for instance, wrote an essay savaging the middle class in mid-nineteenth century. We had to study this in our school and it has remained a prescribed text in Bengal for more than a century. Today you cannot introduce such a text in much of India without probably precipitating a political controversy and demands for censorship.

Recently, at a lecture organised by the Information Commission of India, I claimed that the future of censorship and surveillance in India was very bright. It’s not only the government that loves it but a very large section of middle-class India too would like to silence writers, artists, playwrights, scholars and thinkers they do not like. In their attempt to become a globalised middle class, they are willing to change their dress, food habits and language but not their love for censorship. We should thank our stars that there still are people in our midst—editors, political activists, NGOs, lawyers and judges—to whom freedom of speech is neither a value peripheral to the real concerns of Indian democracy nor a bourgeois virtue but a clue to our survival as a civilised society.