The Constitution clearly says the country’s President will appoint the governors. It’s another matter that the nominal heads some states get can become controversial, leaving the system blemished. After all, whichever party is at the Centre, it tries to appoint its committed party members as state governors.

The governor should be impartial and objective so as to earn people’s faith. The Sarkaria and Venkatachaliah commissions strongly suggest disqualifying persons from becoming governors if they are active in party politics. But then, quite a few such candidates have functioned impartially in gubernatorial posts, while it’s sometimes an academician or jurist who may act as a crony of his party bosses.

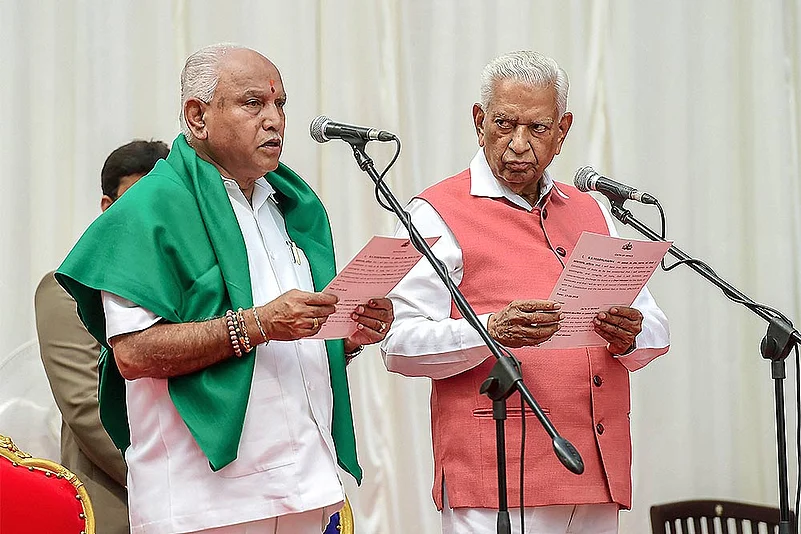

Article 164 says the governor shall appoint the chief minister, and that the appointment of other ministers will be made on the CM’s advice. In the recent case of Karnataka, though, no government was yet appointed; so the governor had to act on his discretion. Article 163(2) categorically provides that a governor’s discretionary act cannot be questioned on grounds of invalidity or what (s)he ought or ought not to have done. The Constitution places the post at a high pedestal.

The governor may go wrong, as he did in Karnataka—or as the President did in the case of Atal Behari Vajpayee as the PM in 1996. Even Charan Singh never faced the House, but was appointed prime minister (1979) by the President in his discretion. The perceived dubiousness associated with that precedent cannot take away the President’s power to appoint PMs. Nor can the present Karnataka governor be shorn of his constitutional powers. If even the Supreme Court tries to go against specific words in the Constitution, that would be unconstitutional.

I disagree with some courts that mala fide or lack of relevant information can subject a governor’s discretionary acts to judicial review. The judiciary cannot take away the powers of other authorities. Every House is free to decide rules in accordance with the Constitution. Courts have said that the single-largest party should be called first, then coalitions, pre- and post-poll alliances. These are recommendations—such rules don’t exist in the Constitution.

Courts may interfere in the appointment of a PM or CM, but that denigrates Parliament and legislature. In Karnataka, the court laid down procedures for the assembly: on who should preside when a motion should be taken up—and that it should be the pro tem speaker. This never happened before. Despite recent bad behaviour by its members, the legislature is the supreme institution of representatives of the people. Who commands majority support must be decided on the floor of the House—not on the lawns of Raj Bhavan—by political parties submitting lists or the parading of MLAs before governors. It can also not be done by courts.

When political parties talk of strength, they refer to seats won in elections, not numbers in support of government. The Constitution gives members the freedom of vote and speech in the House. Support in the House means those present and voting. There is no direction as to which way elected members must vote. Yet, the Karnataka governor was unjustified in giving 15 days to the CM to prove majority. Though there is no provision, reasonableness is expected. This was too long.

Democracy is very much threatened—it has been for quite some time. Perhaps we need to revisit, reinvent and reform our democracy. The Venkatachaliah recommends one solution for when it’s unclear who commands majority: Under Article 175(2), governors can send a message to the assembly, seeking to discover who the House has confidence in. The pro tem speaker can conduct the procedure of election of leader of the house, who may be appointed CM by the governor. Here the governor appoints pro tem speaker, as per the Constitution, and is also aided by the House. Thus he moves beyond controversy. In Jagdambika Pal and Kalyan Singh, the Uttar Pradesh House elected the CM. That can be followed in hung assemblies, restricting a governor’s powers to appoint the CM.

People compare the Karnataka story with that we recently saw in Goa, Manipur and Meghalaya, but no governor is bound by another governor’s decision. Some as governors or Presidents, may occasionally misconduct. For that, there is no remedy.

(The writer was secretary-general, Lok Sabha.)