If the security forces can treat dead women like hunting trophies, not only trussing their bodies to poles, but taking pride in displaying their kill, is it surprising that their behaviour towards the living is so atrocious? After every deadly attack by the Maoists, ‘civil society actors’ are summoned by TV channels to condemn the incident, substituting moral indignation for news analysis. And yet, the same media is strangely silent on police or paramilitary atrocities against civilians. On June 9, The Hindu published stories of rapes in and around Chintalnar in Dantewada by special police officers (SPOs) of the Chhattisgarh government. To my knowledge, no one’s asked P. Chidambaram, Raman Singh or the Chhattisgarh DGP to condemn these incidents or even asked what they are going to do about it. These are people in positions of power, who are elected or paid to uphold the Constitution, and the ‘buck stops with them’, not with ordinary citizens.

If channels can run all-day programmes on justice for Ruchika Girhotra, why not for the adivasi girls who were raped and assaulted in and around Chintalnar between May 26-28? Is it because they are not middle class and their plight will not raise TRP ratings? Or because they are considered ‘collateral damage’ in the war between “India” and the “Maoists”—who, not being part of “India”, are presumably from outer space—that TV commentators advocate?

While rape is often described as a weapon of war, it is not uniformly practised, and indeed nothing distinguishes the two parties in a guerrilla war more than their attitude to rape. In her careful analysis of sexual violence during civil war, the political scientist Elizabeth Woods points out that while it was common in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Rwanda and Sierra Leone, sexual assault was less frequent in El Salvador, Sri Lanka and Peru. In the latter cases, the vast majority of rapes were committed by the government or paramilitaries, this also being a primary reason why women were motivated to join the insurgents. The rebel armies—who carried out other violent acts, including the killing of civilians—almost never committed sexual violence, including against female combatants in their own ranks. In Mizoram, women recalling the regrouping and search operations of the 1960s described only rapes by Indian soldiers and none by the Mizo National Front. One said to me, “It is as if the vai (outsider) army was hungry for women.” Today, despite government claims that the Maoists sexually exploit young women, the distinction between insurgent and counter-insurgent is clear for the women of Dantewada. They are safe from one army (the PLGA) but not from the other (the Indian paramilitary and SPOs/police). And in any war to win hearts and minds (‘WHAM’), surely this is not an unimportant distinction.

After the 76 CRPF men were killed at Chintalnar, many in the media pointed to the complete lack of intelligence on the ambush. What kind of intelligence do they expect from villages from where young girls are picked up and kept as sexual slaves in Salwa Judum camps? In July ’08, I recorded two testimonies from the village of Mukram, right next to the site of the attack. These, along with several others, were submitted to the nhrc, which was investigating the situation on behalf of the Supreme Court, and to the National Commission for Women, but till date, nothing has come out of it. But this is how the testimony of Kawasi Lakhmi (all names of victims changed) went:

“I was four months pregnant and was visiting my parents’ house in June 2007 when Salwa Judum leaders and SPOs attacked my village. It was about 9 or 10 pm and I was sleeping when they surrounded my house. They beat up my parents and dragged me to the main road. From there, along with Hidme and Madvi Unga, a 20-year-old boy, I was taken to Jagargunda camp. There I was kept for a week and raped every night by different SPOs. I do not recognise the others, but I recognised Bhima aka Ramesh of Jonnaguda village and Somdu of Kunder village.

“We (the two girls) were kept locked up in one house and Unga was kept separately. We were given only a little food and not allowed out at all, except to relieve ourselves. My clothes fell apart in tatters and my jewellery was taken away. After a week, I was given a small cloth to cover myself. Unga was badly beaten and was ill for a long time. Hidme and I were also ill and could not work for two months. The Chintalnar police took money from our families for having saved us.”

The benevolent police of Chintalnar had told the girls’ families that they had sent a wireless message to Jagargunda camp and the girls were safe. In return for this, they had extracted Rs 1,500 from each family. The same SPOs appear in other testimonies, such as this one from Kottaguda:

“Around April ’07, Salwa Judum, SPOs, police officers and CRPF men came to our village. I was on my way to fill water while Kosi was at home at this time. The Judum and security forces caught us, called us Naxalites and forcibly took us to Jagargunda camp. There they kept us in a room where SPOs raped us several times during the next few weeks. We can recognise them and know some of them by name also because they are from nearby villages, like Bhima of Jonnaguda village, Somdu of Kunder village, Dasru of Millampalli, Nanda of Lakhapal village and Muka of Nagram village.”

Another common pattern that emerges is of gangrapes by SPOs on combing operations. For the young girls, who have so little to begin with, the loss of jewellery and clothes is an important part of the narrative. And yet their resilience in the face of horror is remarkable. A 17-year-old I met in Arlampalli village recounted:

“On July 29, ’07, I was breaking tora in the courtyard of my house when four SPOs came. I ran inside but they dragged me out and took me about one km away. There they tied my hands and feet and blindfolded me and all four gangraped me. They tore all my clothes and broke my jewellery. After that, I managed to escape on the pretext of drinking water and hid in a grain bin in someone’s house. I recognise three of the SPOs—Rajesh from Polampalli, Kiche Soma of Korrapad and Linga from Palamadgu. Even after this incident they came to my house and threatened me. I was too scared to report to the police and, anyway, what would have been the point? I was even too scared to go to the market for fear of being caught and raped again. After being beaten and raped, my body was badly swollen. I was also bitten by a snake while running away that day, but could not go to a doctor. I was treated with local medicine.”

Nothing brings out the hollowness of the government’s claim on WHAM more than its stand on sexual violence. Rapes cannot be justified as actions done in the line of duty. Unlike an encounter, there is no question of who fired first. Even if rogue police or armymen commit rapes, a concerned government can take steps to identify and punish the guilty. And yet, the record on this is abysmal, from Kashmir to Manipur to Chhattisgarh. In practice what emerges is that, rather than WHAM, the Indian government is following a ‘cost-benefit approach’ aimed at making the costs—including starvation, murder, torture and rape—far higher than any benefit the public might gain from supporting the guerrillas or remaining neutral.

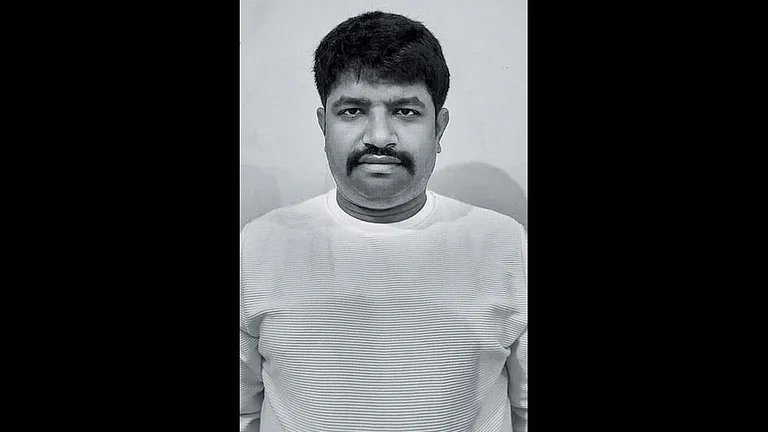

In Dantewada, the police have bent over backwards to defend the SPOs and Salwa Judum leaders accused of rape. Take the case of Markami Budri, originally from Bhandarpadar village. In March ’09, she wrote to the Dantewada SP complaining that she had been raped by SPOs in Konta thana, who picked her up when she was on her way to a relative’s house. Among those she accused was one Soyam Mooka, Salwa Judum leader in Konta. Since the SP refused to file an fir, she and five other girls were helped by a local NGO to file a case in the lower court. Her first deposition was on June 16, a hearing which the police clearly had knowledge of. In the meantime, we had already filed her complaint with the Supreme Court. In a letter to the SC dated June 17—a day after her court deposition— the SP Dantewada wrote that “the police enquired about her”, and “nobody knows as to where she has gone away”. Further, the people he had enquired from, Salwa Judum leaders Boddu Raja, Soyam Mooka and Dinesh (the very people accused by her), claimed the charges were fabricated to malign them. On October 30, the Konta magistrate issued an arrest warrant for Soyam Mooka and the other accused. On December 10, the police declared they were all absconding. But less than a month later, on January 6, 2010, Soyam Mooka was seen under police protection leading a demonstration of the Ma Danteshwari Swabhimaan Manch (a new name for the Salwa Judum) against Medha Patkar and others in Dantewada town.

Once rapes become routine, what any responsible commander should be worried about is not so much the brutality of the other side, but the degeneration of his own. The victims will be not just the adivasi women of Dantewada or Lalgarh, but women from all the areas where the jawans come from. What do we want—an India at war with its women?

(Nandini Sundar is the author of Subalterns and Sovereigns: An Anthropological History of Bastar 1854-2006.)