The literature portion of the Jaipur Literature Festival died sometime last week. We all know why. One can only express one’s sincere condolences. What remains is a festival and a pink city tagged on to it as a prefix. What is left to be done is the gushing over Oprah Winfrey and the applauding of Chetan Bhagat. Someone will be sweeping the confetti soon.

The organisers of the Jaipur Literature Festival have been in this position before. The idea of the kind of literary festival that they have chaperoned has shown signs of having developed a terminal illness for some time.

Sometime last year, they tried to organise a festival they wanted to call ‘Harud’ (autumn, in Kashmiri) in Srinagar, somewhat along the lines of what they do in Jaipur. Initially, this move was heartily welcomed. Kashmir, like most places where formal and informal curfews kick in early in the evening, has an extremely lively contemporary literary culture. Like in the former ussr and Eastern Europe before the Berlin Wall came down, when you can do nothing else, you read. Literature is the only beacon of freedom in an unfree territory. And people tend to read what they want to, not what they are told to. Ours is a samizdat time.

Against this context, the JLF organisers, while prefacing their plans for Harud, declared that they wanted the festival to be a celebration of ‘apolitical’ literature. A festival of apolitical literature in Kashmir is about as interesting as an exercise in expressing one’s love for literature (as the press release by the JLF in defence of its despicable act of distancing itself from the writers who did the right thing by reading extracts from a book banned under Section 11 of the Customs Act would have it) ‘within the confines of the four corners of the law’ in Jaipur, or indeed, anywhere. It is no wonder Harud was still-born, and that the JLF is now effectively deceased.

Festivals, be they festivals of cinema, theatre, art or literature anywhere in the world, are respected as spaces where the censor is forbidden. A few years ago, when the Mumbai Documentary and Short Film Festival tried to impose a requirement of ‘censor certificates’ from Indian participants, they were effectively shown the door by filmmakers who decided to start their own ‘uncensored’ screenings. If the JLF now demands guarantees from prospective participants that they will respect bans imposed by idiots, they will have effectively ensured a complete boycott of themselves by all self-respecting writers, not just in India, but all over the world. There will also probably be a mushrooming of small, self-organised and free literature festivals all over India. They will save on air fares and hotel bills by inviting well-known writers on Skype in venues that are not palaces and keep their distance from the literary preferences of the real estate mafia and mining companies.

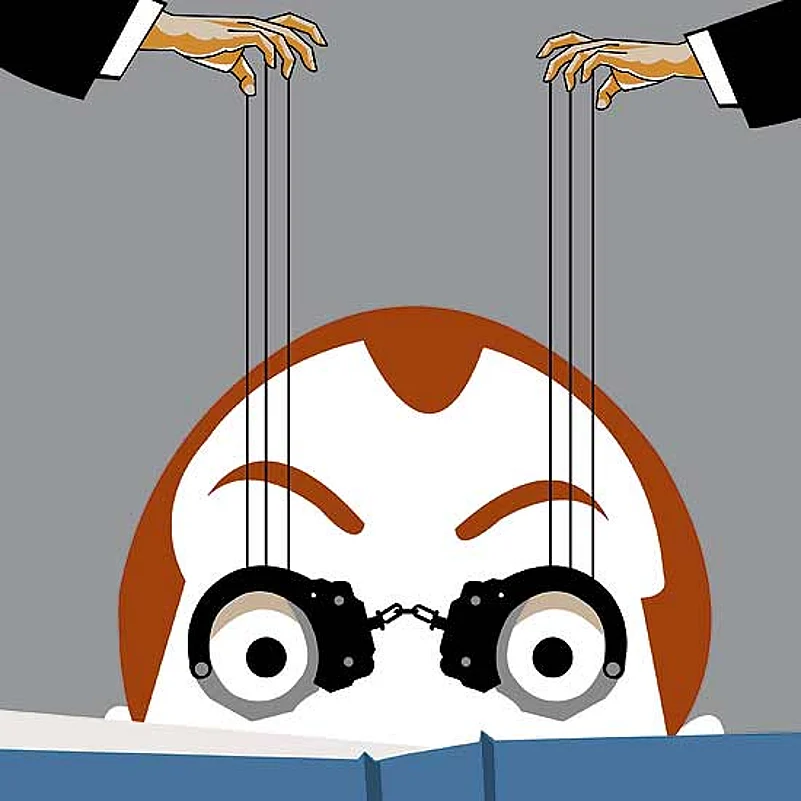

Elsewhere, (on Kafila.org), I have pointed out that a love for literature confined within the four corners of the law is an apt description of the reading habits of a bookish inmate of Tihar jail, but it cannot and must not ever be the mandate of anything that pretends to be a festival of literature. If the organisers of the JLF have expressed this quadrangular preference as a result of the legal advice they seem to have been so freely offered, we need to ask a series of questions about both the quality of that legal advice and the enormous political and legal naivete of JLF’s organisers in taking such third-rate advice seriously. The infanticide of the Harud Festival and the suicide bombing of the JLF, not unlike some acts of so-called terrorism, need to be seen as a collaborative exercise staged between covert state agencies and a gullible media , who invent (non)assassins to suit the moment with as much alertness as they occasionally manufacture (non)terrorists who are then disposed of in (non)encounters.

Having said all this, it is also time to remind ourselves that we have come a long way since 1988 when the ban on the Satanic Verses was first imposed by another Congress-led government. This time it’s different. If the four writers who did the right and ordinary deed of reading downloaded extracts from an article about the Satanic Verses or from an online version of its manuscript at Jaipur are punished, then the state will also have to consider punishing the thousands who have probably downloaded and read from the Satanic Verses in the last few days in India. A very civil disobedience of readers is afoot, as is evident from Facebook forwards. Bookish people tend to be fanatics too, and if this government, or any government for that matter tries to police the boundaries of their reading, they will be faced with the gentle, but sharp insurgency of the written word. The Jaipur Literature Festival may have died a premature death, but literature, thankfully, is alive and kicking.

(The author is an artist with the Raqs Media Collective)