Recently, when our members of Parliament gave themselves a pay hike, there was a predictable howl of outrage across the country. The fury wasn’t directed at the antics of some MPs—led by the gimmick-prone Laloo Yadav—who denigrated the institution by conducting a mock parliament after hours in the Lok Sabha chamber. Instead, commentators were venting their ire on the magnitude of increase in salary and perquisites while, predictably, missing the larger, more important issues.

Let us consider some of the criticism: that the salary hike, from Rs 16,000 to Rs 50,000, and increase in perquisites, are obscene; that given the decline in days when Parliament did its designated work, a raise is unjustifiable; that Parliament is filled with crorepatis MPs so it’s hard to see them needing a raise at all; that representatives shouldn’t be earning many times the average per capita income of their constituents etc, etc.

So if these aren’t the real issues, what are? Start by considering the roles and expectations from an MP. These go substantially beyond passing legislation or holding governments to account through searching questions and aggressive opposition. MPs perform multifaceted roles, partly by choice, partly because voters expect them to. They serve as quasi-ceos of their constituencies, and are expected to bring home projects that trigger development. The MPLADS funds each MP gets is a pittance compared to the costs of (locally relevant) projects that constituents demand. MPs are also expected to address voters’ grievances, from problems with the bureaucracy to getting jobs and admissions. They must often contribute cash at functions or help out with acts of charity. And MPs are expected to be super-knowledgeable about the issues of the day.

If you were to spend a day with an MP, you would see the enormous costs of just keeping the show running. Visitors expect tea-coffee or meals, staffers have to be on hand to handle phone calls and mail. And then there’s the need to organise political meetings to stay alive politically.

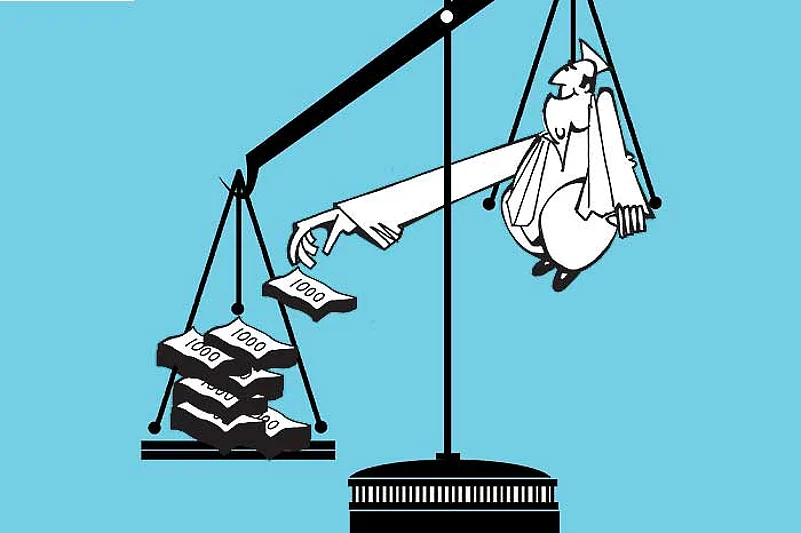

The salary hike barely covers the real costs of being an MP in modern India. Any MP who remains honest is well on his way to becoming insolvent. Indeed, some years ago, the professor-turned-minister Yogendra Alagh had stated that his wife advised him to reject another term because their budget couldn’t cope with the expenses of providing tea-coffee to all those visitors. Similarly, PM Manmohan Singh may have ushered in prosperity for India but clearly hasn’t done much for himself. His assets accumulated over a life-time are easily matched by MBAs today before they turn 30.

When we focus on the crorepatis and not the Alaghs and Manmohans, we implicitly concede that there is no space in Parliament for honest politicians. When we criticise salaries and perks that in some small measure address the costs of being a representative, we are condemning MPs to make compromises just to do their job. Such arguments ensure that people of integrity will be pushed out of political leadership. Is that what our commentariat really wants?

The larger issue is about political careers. MPs are the lucky ones who get an income and perks to perform their roles. Half of them will not get re-elected, yet will need to stay politically active without salary or power. For democracy to flourish, there needs to be intense competition to become an MP. In India, incumbents and challengers are both expected to perform many of the same roles. Given our huge population, it is a costly, full-time job to keep in touch with voters, to mobilise politically, to stay active in the party etc. And if one succeeds in getting a ticket, the costs of conducting an election campaign dwarf the costs of being a representative.

Becoming a politician, then, is highly risky career-wise. The costs are already stacked against people of integrity. The carping by the chatterati only makes the situation worse. We cannot run a representative democracy without elected representatives. We need to attract people with vision, policy knowledge, diverse capabilities and integrity to politics. There are ways out: in Singapore elected representatives are paid salaries pegged to those earned by top executives in the private sector. In the US, representatives are provided with substantial staff and support in addition to decent salaries. Adopting similar measures here, and cleaning up political contributions, will dramatically change the quality of Parliament members and their performance. Unless we focus on such larger issues, the flood of media criticism on MP pay hikes will only guarantee that we remain the world’s largest hypocrisy.

(Professor Gowda is chairperson, Centre for Public Policy, IIM Bangalore.)