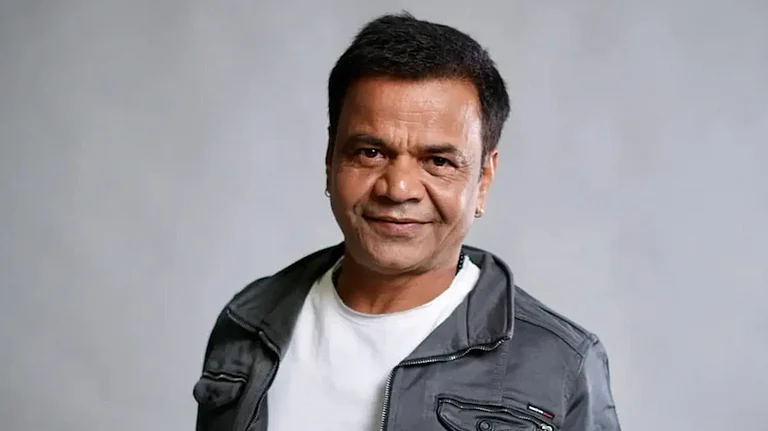

With the Taliban taking over Afghanistan, geostrategy expert and retired intelligence officer Anand Arni, speaks with Bhavna Vij-Aurora about possible threats to India. A former special secretary at the cabinet secretariat, Arni was part of the team sent to Kandahar to negotiate with the IC-814 hostage-takers in 1999.

Having closely observed how the Taliban works, how do you assess the current situation in the neighbourhood?

The key question is Pakistan. Once the initial euphoria wears off, Pakistan’s concern would be Pashtun nationalism, since a take-over by a largely Pashtun force in a neighbouring country could have implications in their frontier. They would also need to convince the Taliban to address the Durand Line (the international land border between Afghanistan and Pakistan) issue, which the Taliban refused to deal with the last time. It’s too early to say what will happen this time, but this could become a source of tension. There are other issues too. For one, the Taliban old guard are no great friends of Pakistan, and if the latter starts asking for too much, there is bound to be pushback.

Then, there is the refugee issue. If relations sour, or if Taliban return to past ways, with curbs on women and education, or there’s renewed fighting, or if the economy totters, there could be an influx of refugees, which will create problems for Pakistan.

How will that impact India?

I don’t think we should expect, or be in any hurry, to do business with Taliban immediately. They need international acceptance, as they need aid to keep their country going. Pakistan cannot sustain it on its own. As the Taliban look for international acceptance, they are bound to look at India more carefully. We have to wait and watch.

There are reports India has been talking to Taliban factions, with even foreign minister S. Jaishankar meeting Mullah Baradar in Doha in June.

The level of contact is unclear. There have been meetings in Doha, which could have involved Baradar. Either way, he would be in the know. There may also have been more subterranean contacts. And if these haven’t happened, then I’d say we have been rather short-sighted.

With Taliban in control, any threat to India or increase in cross-border terrorism?

Even in the 1990s, not many Afghans infiltrated into Kashmir. I think in those days there were at most 1-2 batches, consisting of 25-30 fighters, who came to the Valley. For the Taliban, the resistance against foreign domination has been the prime motivation. I don’t see a major threat of jehadis flocking to cross the border in Kashmir for the next jehad. That said, there are many sub-groups within Taliban. The rank and file are Afghans, but there is another group, whom I call Pakistani Afghans. That second group, brought up in Pakistani refugee camps and educated in madrasas there, probably joined the Taliban after being brainwashed. They are more Pakistani than Afghan.

I don’t see the Afghan Taliban coming across here. Maybe a few, but not in great numbers. The same cannot be said of Pakistani Afghans. They need a cause and could pose a problem. For one, they may be more amenable to trans-border jehad. But will ISI encourage them? Crossing the border needs money, equipment and assistance.

There is no reason for complacency, though. What has been happening in Afghanistan could play out in the Valley in a different sense. The so-called ‘vanquishing’ of a superpower could be emotive, and Kashmiri youth could suddenly think it is possible to take on the authorities the way Taliban got rid of the Americans.

There could be outsourcing of some skill sets, like how to make different IEDs or use drones. Some bombmaker may visit the Valley, help assemble weapons and gadgets, and then disappear at the time of the operation. Also, weapons—Afghanistan is awash with US weaponry that could land in Kashmir. And of course, they could just run training camps in the ungoverned areas. Last time, there were camps in Loya Pakhtika—the Haqqani network’s lair—and we all know Haqqanis are an arm of the ISI.

We’ll also need to see how the Taliban handle the export of jehad and such training. They have given assurances they won’t allow their soil to be used against other countries. They may well be earnest about international terror outfits like Al Qaeda and ISIS, but what about ISI and other jehadi tanzeems?

People waiting to be evacuated in Kabul

What about Lashkar-e-Toiba (LeT)?

Lashkar is, of course, the elephant in the room. The organisation was actually set up in Afghanistan in the late 1980s, and has been active there for over a decade this time around. The fighting in some areas is said to be by the LeT. Several hundred LeT terrorists have reportedly been spotted in Kunduz and Kunar. They bring in new technology—we saw their Special Forces skill sets in Mumbai. A drone that was brought down in Kunduz last year was reportedly operated by the LeT.

The other danger is outsourcing—some years ago, an LeT bombmaker was arrested in France. LeT cadres have also joined ISIS, and recently, a former LeT-ISIS cadre was appointed head of the ISK (Islamic State-Khorasan, the ISIS franchisee in Afghanistan).

Also, Pakistan needs a force inside Afghanistan to keep anti-Pakistan sentiment in check, maybe to ensure the Taliban don’t bolt. The LeT is their insurance.

How will China, Pakistan and Russia’s support to Taliban affect the region’s geopolitical situation?

For the past 40 years, many of these countries have been blaming the US for all the problems in the region. We all know how it started, how US propped up anti-Soviet mujahideen fighters. The Americans had links with the Taliban in the 90s. Afghan-American diplomat Zalmay Khalilzad even negotiated with them as a UNOCAL (Union Oil Company of California) representative. Clinton’s assistant secretary of state Robin Raphel met them in 1996 or so.

Each neighbouring country has its own vulnerabilities. Many Islamist groups working against these governments are seeking or have found refuge in the [Afghan] north. It’s a cause of concern.

In its original iteration, ISIS had a large number of Russian speakers, including Chechens, Dagestanis, Uzbeks, Tajiks and even ethnic Russians, who could gravitate towards sanctuaries in the north. And of course, Russians are also deeply worried about narcotics, the flow of which they consider their single biggest threat. There are Uyghurs in the Wakhan corridor and in Badakhshan, but I think it is manageable for China, unless it is left unchecked, or there is external stimulus.

I doubt the Chinese would immediately enter Afghanistan. Why would anyone jump the gun about a country that has been a graveyard of three empires, maybe four, unless there are enough guarantees? It’s too early to say who would be interested to invest in a country that is so insecure and volatile.

That said, their footprint will increase, especially after the situation stabilises, and do something with Afghanistan’s resources.

How should India deal with the Taliban?

Patience. Let’s see how it plays out.