The whole planet’s eyes are on us—on Kabul, freshly captured. But on Wednesday, August 18, a presaging of what may lie ahead for Afghanistan came from a town some 240 northwest of the capital city. The central highlands are a landscape carved with dramatic cliffs and caves, mysterious places that have now revealed the world’s oldest oil paintings. Here, back in March 2001, the Taliban had thrown down perhaps their most stunning challenge to history. Bamiyan: the very name suffices to bring up, with a shiver, memories of the giant 6th century Buddha statues being pulverised into nothing. Now, Abdul Ali Mazari was no Buddha. An advocate of federalism and equal representation, he was also party to the endless civil war that beset Afghanistan before and during the Taliban’s first arrival on the scene in the 1990s—till he was tortured and murdered in 1995. Ashraf Ghani, the deposed president who fled the country on Sunday, had called him ‘Martyr of National Unity’. But on Wednesday, the Taliban dealt Mazari a symbolic second death—blowing up his Grecian-style statue in Bamiyan.

There’s a mismatch between that act and how things were presented in Kabul, post-takeover. Just a day ago, Zabihullah Mujahid, the secretive Taliban spokesman who no one had ever seen, had come out in the open after 14 years and spoken calm, conciliatory words at a press conference. No revenge, no conflict, no internal enemies, no executions, no hounding of journalists, no oppression of women, he said. A day later, the Mazari statue came down. Now, Bamiyan is the heart of Hazarajat region; Mazari was a leader of the Hazaras, a persecuted ethnic minority who follow Shia Islam. This symbolic execution can only be an ominous sign—a sign that the words spoken by the Taliban representative may only have been part of an image-building exercise meant for the international community.

Urban Afghans don’t trust the Taliban either. The international community has left us alone...to fend for ourselves. Fear is palpable. It is everywhere, clinging to you. It is in people’s faces, in their nervous movements, whether in the neighbourhood street corners or the city’s crowded bazaars, in the drawing rooms of the well-to-do, or the slums where people are gathered in small clusters watching the news on their mobile phones.

In Kabul, the people are simply terrified at what tomorrow may bring. Videos are circulating of what the militiamen are doing in places they have captured. The thought in every urban Afghan’s mind for the last 10 days was: this could be my fate when they come into the city. Now that moment has arrived. Reports, pictures and videos of torture circulated everywhere, rumours of beheadings flooded every mind. It all seemed so savage and brutal and scary. Will the Taliban keep its word about preferring peace? No one knows.

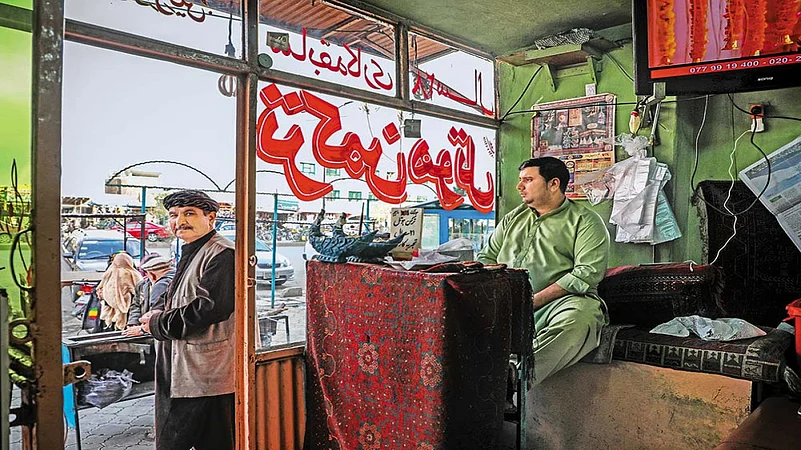

Snapshots of life in Kabul and on its outskirts just before the Taliban took over, as seen through Roya Heydari’s lens

Still, after 20 years of a free society, it is traumatising to think of such a radical change in life. For many of us, a nightmare we had never even imagined. I am luckier than most others. I am alone in Kabul. My immediate family and close relatives are abroad. But I see the condition of my friends and colleagues who have wives, children, parents and extended family all living in the country. My female friends are especially mortified. They know well that their careers and their studies would be severely affected. None of us believe that the Taliban have changed—despite the fond hopes of some that this is not the Taliban of Mullah Omar. We don’t buy into the narrative that the times have changed, and that the times have in turn changed the Taliban. In Doha, the Taliban always sing a different tune to the international community. But on the ground in Afghanistan, they are a carbon copy of their past avatar.

No one had thought the government was so unprepared. When we spoke to officials and ministers, they had exuded confidence that the Afghan National Defence and Security Forces (ANDSF) were in a position to defend the cities. And citizens backed the government. In Herat, when the Taliban was initially repulsed, citizens came out to the streets and rooftops shouting Allahu Akbar. After the attack on the defence minister’s residence in Kabul, when the security forces and police destroyed the Taliban squad, there were again cries of Allahu Akbar across Kabul.

None of us imagined the ANDSF would cave in like this. A group of us had met former president Hamid Karzai a few days ago. We also met some senior security officers. They said Kabul would be defended. That it would not be a walkover for the Taliban. They looked confident. They also said the ANDSF would fight back in Ghazni. But look what happened. The Taliban overran not just the countryside, but an entire roll-call of cities. They fell like nine-pins. Kunduz, Herat, Ghazni, Nimroz, Farah, Ghor, Badghis…one after the other, the cities were gone. And now, Kabul too. At one point, 17 of Afghanistan’s 34 major provincial capitals were under Taliban control—and we knew the tide was turning. Especially when heavy clashes were under way in the centre of Logar province, a mere 70 km south of Kabul. Everyone sensed it was just a matter of time—that they would be at Kabul’s gates in two or three days. Just days ago, intense fighting was being reported from Kandahar, but on Tuesday, Taliban co-founder Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar returned after 20 years. In Khost and Jalalabad, there are still protests in support of the old Afghan flag. But it is the endgame. They say Mullah Baradar is likely to be president. Karzai and his team had already started negotiations with Anas Haqqani, a leader of the eponymous Haqqani faction (which the US lists as a terrorist network), late on Wednesday—eventual talks with Baradar will be the next course arriving at the table.

People are angry at the government of President Ashraf Ghani, the man who had initially put up a show of defiance. When the Taliban had demanded that he step down, those in the know said he would rather die defending what he believes in. Look at his flight from centrestage now. People are also angry at the US for letting Afghanistan down. We feel bereft, unwanted, abandoned. Afghanistan has been the theatre for big power rivalry down the ages. We have been pawns for the proxy wars of great powers. Starting with the Great Game, when Afghanistan was the buffer to keep off Russia, the Anglo-Afghan wars were fought for the empire’s strategic interests: Afghans didn’t count even then. Again during the Cold War, the Soviet Union and the US used Afghanistan as their battleground. Once the Soviet army withdrew, the Americans lost interest. They sent in their forces only after 9/11, to get Osama Bin Laden. After 20 years of the most slipshod, most expensive conflict, they leave this country to its fate. In what book of democracy is this fair? Now the Americans are sending in troops to ensure their diplomatic staff is safely withdrawn. What about our people? Are Afghan lives not important?

Everything is not what it appears like, of course. Afghanistan is the shifting nodal point of a complex game, with any number of world powers batting for their own self-interest. Nobody is sure who is acting at whose behest. Rival powers use Afghanistan for their proxy wars. Wheels within wheels. There are reports coming from the north that in several places the Afghan army surrendered to the Taliban without offering any resistance. Conspiracy theories are rife. Who asked them to surrender? Some say it is the central command of the army that ordered the men to lay down arms. There are too many unanswered questions. It cannot be the case that the army simply caved in without even a semblance of a fight. Who is playing games here?

In the last few weeks, the US and the rest of the international community had warned the Taliban that if they grab power through war, they would not be recognised as a legitimate regime by the world. That Afghanistan would once again be ostracised. Are the Taliban bothered about legitimacy? Beyond a point, I doubt it. Yes, Zabihullah Mujahid’s press conference showed a new desire to be accepted by the international community. But for them, putting their stamp on Afghanistan is more important. Once formally installed, global engagement will be on their own terms.

While most people in the cities are anti-Taliban and do not want to give up the freedom they enjoyed for 20 years, there are some sections among the Pashtuns in the city who were waiting to welcome and celebrate the Taliban’s victory. When the news of Ghazni falling to the Taliban had come in, there was celebratory firing not far from my neighbourhood. Once the Taliban starts ruling the streets, these people may start pointing out those who had collaborated with the government. I shudder to think what will happen.

(This appeared in the print edition as "20 Years Fell Like Nine-Pins")

(Asad Kosha is chief editor at Kabul Now. This report was narrated to Seema Guha over several phone calls.)

Text by Asad Kosha in Kabul; Photographs by Roya Heydari