It does not happen often with a photographer that he cannot bear to look at the image he has captured. But then he realises that he must not only face the photograph himself but show it persistently and insistently till that hard to bear reality reflected in the image transforms. This is what happened last year, when my team and I walked through villages of Assam and tribal areas in Chhattisgarh, capturing the hidden hunger of children and women.

Now, I dread to think what Corona Virus Disease- 19 [Covid] and the lockdown prompted by it are doing to a two year old Rakesh in the Gond community in Chhattisgarh, toddler Bhoni in Dibrugarh of Assam and baby Ajit in Karlapat of Odisha. What are income losses, disrupted food supplies doing to several others we met who were already living on one meal a day? On this World Hunger Day, do we realise that for millions of those surviving on the brink of extreme poverty in our country, less pay means less food, and no pay means no food?

This face and form of hunger has haunted me for past two decades, as I entered homes in Kalahandi of Odisha; tribal areas in the Dongargaon and Naxal neighbourhoods of Manpur and Kanker in Chhattisgarh; villages in Kharupetia and the tribal zones in Bodoland Territorial Council area of Assam; the region inhabited by Warli tribe in Gadchiroli, Thane and Palghar of Maharashtra and Ho and Santhal inhabiting regions of Chakradharpur in Jharkhand.

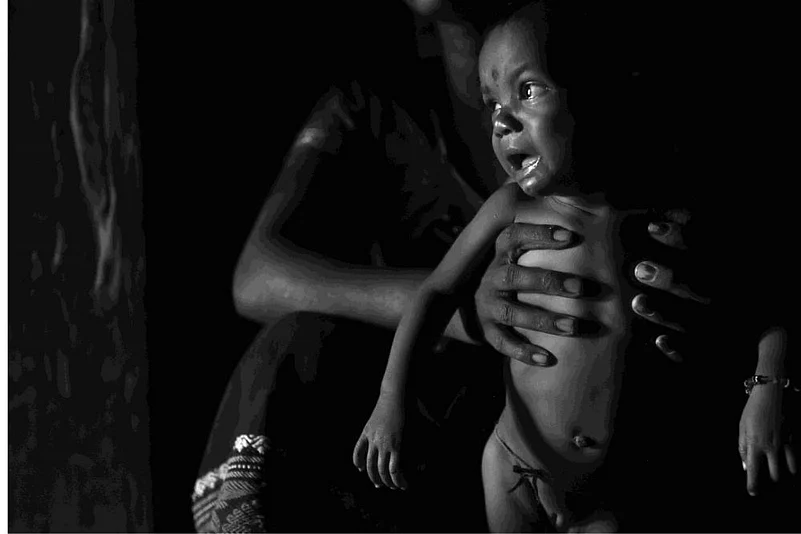

It was much later, that I realized that the wiry thin body, distended belly, large listless eyes, bony limbs, swollen feet that I encountered in home after home has a name in science---Severe Acute Malnutrition or SAM. Also, that this condition, would stop bodies and brains of children from growing and functioning normally. Many of them will go untreated and grow up with lower intelligence and higher risk of illnesses. These children, and their equally reed-thin young mothers, often still in their teens, were much more than subjects of my camera; they were part of my life, as I had become part of theirs.

This emotional compulsion of saving as many of them as is possible led me and my team to intensify our work last year, and chronicle their stories in visual medium by exhibiting telling pictures through a travelling event ‘Endangered Species—Malnutrition Stalks India’s Children’, particularly in cities, like Delhi, which if willing, could significantly alter the trajectory of these children for better, by improving policy design and interventions.

Visibly shocked by the pictures, the audience of intelligentsia repeatedly asked me about ethics of my work—doesn’t it intrude on the privacy of ‘vulnerable subjects’? Truth be told, privacy is a privilege of those who have triumphed in the game of survival. Those I mingle with and photograph are often eager to share their stories if it could help their children, and people like them in any way.

Because, in most cases, I didn’t speak their language, and they didn’t speak mine, an interpreter was present to facilitate that understanding, but one really didn’t need an interpreter to absorb the distress of their context. The language of pain that gets communicated through eyes needs no translation. Most of them were more generous than just sharing their stories. It is ironical, that while I was capturing severe malnutrition in still frames, of those who wage a daily struggle for food themselves, they offered me tea, and local munchies. That melted my heart even though my work of freezing frames in fires, floods and riots has taught me to deal with life’s extremities. And yet I do not tell my audience, that despite their shock, they haven’t still seen the worst, which I have kept aside to preserve the dignity of those who so trustingly allowed me into their lives.

My shots depicting severe malnutrition were just a doorway for city-dwellers to the disturbing lives of hunger from the glitz of malls and mobiles, which severely restrict the vision. [That is one reason I use black and white. Colours distract from the story of life, survival, and death, which are plain truths.] The fuller story of their threadbare existence hanging on a delicate balance can only be experienced while one is among them.

Since I have witnessed these lives firsthand, I am deeply worried by the reports of what Covid and its after-effects are doing to their fragile existence. A staggering 67% of workers in India

lost their jobs during the lockdown, estimated Azim Premji University, based on a large-scale multi-state survey. Around half the households said that they did not have money to buy even a week’sworth of essential items. Over three-fourth of Indian homes reported consuming less food than before. What does this mean for people who were already surviving on one meal a day?

The World Food Programme (WFP) projects that acute hunger is likely to double by the end of 2020. The head of WFP David Beasely has warned of a hunger pandemic comprising multiple famines of biblical proportions within a few months. Hundreds of my subjects ‘eat as they earn’, and these are not mere statistics for me.

Even their ‘normal lives’ were far from normal. The toilets made to make India open defecation free and raise sanitation standards were often without septic tanks. They were often home for goats, or doubled up as storerooms. This while villagers defecated outside, which straight went to waterbodies from where Anganwadi workers fetched water. Many times, Nutritional Rehabilitation Centres, [NRCs, the centres to treat malnutrition victims] we visited were understaffed and out of ration stocks. Even the basic health outreach services we had are now reported to have stopped at many places due to panic of pandemic. So, while commending the recent government announcements of handing out dry-ration, and cash-transfers, I doubt if that will be adequate in the crisis we are living, when they were so inadequate even in ‘normal times.

If we do a survey today, on how many people are eating fewer times than normal in a day, and how many are going the whole day without eating, the results may be too shameful to publish. Yet we must ask these uncomfortable questions to draw the right-fitting programmes in a rapidly shifting global reality, just as a photographer I must lift the camera to face the truth again, no matter how unbearable it is.

[Sudharak Olwe is a Padmashri awardee photographer. Soma Das is an author. This piece has been adapted for a column by Das drawing from Olwe's experience]