At the age of 24, with fire in my soul and a nutrition degree in my hands, I was raring to go—to address the issues of under nutrition in rural India. Not being exposed to the rural lifestyle ever, several surprises awaited me along the way. I learnt about the social norms attached to food, several beliefs and taboos and the various power dynamics at family level, that govern the quantity of quality of food consumed by different members of the family.

It is indeed a pleasure to pen down, mine as well as my team’s life experiences and the way that changed our perspective of nutrition education. One of my earliest memories goes way back to the year 1986, when I visited a tribal village in Gujarat for a nutrition awareness programme. I was five months into my first pregnancy at the time. I bonded well with the women on various aspects of motherhood. One of them asked me casually if I was married. The fact that pregnancy without marriage is an accepted social norm in the tribal culture, took me by surprise. I realised that my journey of learning had commenced.

Learning about physiology

Our first roadblock was to clear the myths, deeply engrained in their minds. The various accepted myths were: “If a pregnant woman eats more food, the child in the womb get suffocated; “Eating brinjals would lead to a dark-skinned child;”“White coloured foods would cause difficult labour, with the child getting stuck in the womb” and so on. These beliefs resulted in severe food restriction and, hence, compromised nutrition. The need to teach anatomy and physiology of the body became the need of the hour.

It was truly, a challenge. We painted our digestive system on a cloth and wore it as an apron. Similarly an apron of reproductive system was designed. We demonstrated that both these systems were different and there was no direct connection that could have any effect on the foetus. These tools became very popular and we ended up leaving those behind with them, almost everywhere we went, so that they could pass the word around.

Lunchtime lessons

Contrary to this, I had a very different experience with a community in a poor area of Ahmedabad city. I used to teach basic anatomy to women health workers. In one such visit, I was teaching them the respiratory system, with illustrations. Obviously, I was anxious. They heard me out and then informed me that they are meat-eaters, and have seen and eaten each part of the goat’s body. Naturally, they knew way more about the anatomy than I did. I was yet to see lungs, whereas they had tasted it. They started bringing different parts of the goat during the training to make the learning easy and meaningful. And, of course, during lunch hour, they would cook that particular organ and eat it. An interesting and mutual learning over lunch.

Knowing more leafy greens

Our knowledge of leafy vegetables was restricted to spinach, fenugreek leaves and amarunthus, until we visited rural areas. Hence, this was all that we promoted in our trainings. We gradually observed and learnt that they also consumed a variety of other green leafy vegetables, for instance, leaves of bottle guard, Bengal gram, green gram, beetroots, radish, cauliflower and more. We incorporated their food habits in our training sessions and actively started promoting those.

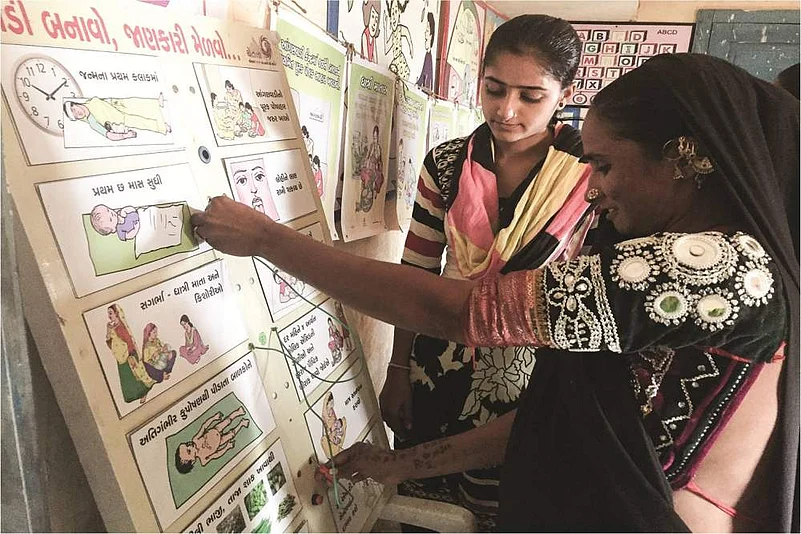

Addressing gender inequality

Neglect and discrimination towards women throughout her lifecycle is a reality, which affects her nutrition status the most. Patriarchy is strongly ingrained in our system. Hence, gender equality and women’s empowerment are the core value of our nutrition and health education. Our training sessions begin with discussions on gender equality and is always based on life experiences. The women and the chairperson, share their personal experiences on the discrimination they have faced in life. For instance: “A friend of mine gave birth to three girls. She was blamed for that and the husband remarried. My friend is so depressed and has become very dull and weak.”

We felt that it was crucial to arm the women with scientific knowledge about the process of sex determination of the newborn child. It was important for the women to know that, it is the man who decides the sex of the newborn child. We introduced a simple exercise to clarify this complex phenomenon of sex determination.

Grains for chromosomes

•The participants are asked to stand in two circles, outer and inner.

•Some are given only rice to hold in both the hands, symbolising X chromosomes. Others get rice and pulses to hold in each hand, with the latter representing Y chromosomes. Women holding rice in both hands represent “woman” (XX chromosomes) and women holding rice and pulses represent the “man” (XY chromosomes). The participants close their fist.

•With music, women in the outer circle start moving clockwise, while those in the inner circle anti-clockwise.

•When the music stops, a pair is formed—one woman from the outer circle, and one from the inner circle.

•The pair open their fists. If both the fists have rice it means that a girl is born and if one fist has rice and the other has pulses, then it is a boy.

This is followed by the game of snakes and ladders. A giant board is created on the floor. The messages written on the game are based on nutrition, with special focus on gender aspects affecting the nutrition of women. Playfully, an important message is conveyed. Other methods used are the “Light Game,” the “Ring throw,” the “Wheel with Window” and so on. We at CHETNA, enjoy learning from women and developing new games and exercises to make our nutrition and health education a joyful learning experience.

(Pallavi Patel, a trained nutritionist, has been working in the nutrition space for more than 35 years. She is a Director and a Founding Member of CHETNA (Centre for Health, Education, Training and Nutrition)