History stands witness to the twists and turns of political fortune the Puri Jagannath temple has been embroiled in over the centuries. The protests voiced recently against West Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee’s entry into the temple to offer puja is in line with the politics the servitors of the deity have always dabbled in. Pre-Mughal Muslim rulers introduced pilgrim tax in India. Emperor Akbar abolished it and Shah Jahan continued this liberal policy. Aurangzeb, however, went back to levying it. Interestingly, the tax continued to be extracted by the Hindu Peshwas who ruled Orissa in the 18th century. Later, the East India Company actually systematised it: a regulation was passed in 1806, classifying pilgrims into four categories, with tax rates varying from Rs 2 to Rs 10 per head. Some Bengali zamindars were known to have visited Puri with a retinue of 2,000 men by paying pilgrim tax.

It was in September 1803 that Wellesley’s army took Orissa—in 14 days flat, without even a shot being fired or a drop of bloodshed. The army marched right up to the outskirts of Puri and camped at Pipili, four miles off the temple town. A delegation of high priests from Puri called on the commanding officer of the victorious army in his camp. Swami Dharma Teertha (1893-1978), whose pre-ascetic name was Parameswara Menon, wrote in History of Hindu Imperialism (1941): “The oracle of the Puri Jagannath Temple proclaimed that it was the desire of the deity that the temple too should be controlled by the Company, and the latter undertook to maintain the temple buildings, pay the Brahmans and do everything for the service of the deity as was customary.” In the very first year, the institution yielded a net profit to the Company of Rs 1,35,000, the swami wrote. Puri was not the only temple town under the British tax net. The Company earned tax of some two to three lakhs from Gaya. Huge tax inflows also came in from other pilgrimage centres like Tirupati, Kashipur, Sarkara, Sambol etc—the net revenue amounted to an average to £75,000 and upwards annually.

By Regulation XI of 1809, the Company banned the entry of the Lolee (or Kasbee), Kalal (or Sunri), Machua, Namasudra (or Chandal), Gazur, Bagdi, Jogi (or Narbaf), Kahar Bauri (or Dulia), Rajbansi, Pirali, Chamar, Dom, Pan, Tior, Bhuimali and Hari castes or sub-castes into the Jagannath temple. The Piralis, considered degraded Brahmins, was the lineage into which Rabindranath Tagore was born. In 1810, the ban against Piralis was revoked. This exercise—the exclusion of many and inclusion of some—was guided by the political wisdom of the priests. The pecuniary gains of the Company, the priests and others concerned were phenomenal. Official reports disclosed that, during the period 1806-32, pilgrim tax collected grossed at Rs 24,57,655 whereas expenditure stood at Rs 12,36,034. The Company treasury swelled during this period by Rs 12,16,174, as quoted in Col Laurie’s article ‘Puri and the Temple of Jagannath’ in The Calcutta Review, September 1848. The average annual gross tax collection aggregated at Rs 1,11,711 and expenditure at Rs 56,183. In Orissa Vol 1 (1872), William Hunter wrote that “not less than 20,000 men, women and children live directly or indirectly, by service of Lord Jagannath”. No contemporary industrial establishment, either on the west or east of the Atlantic, perhaps boasted such a large population dependent on a single institution for subsistence.

The Company shared a portion of the pilgrim tax with some stakeholders. Ten per cent of the gross tax collected from pilgrims of Gaya (Rs 26,078) was paid to the Maharaja of Tekari, who had jurisdiction over the Vishnupad temple, wrote James Peggs in Pilgrim Tax in India (1830). The favour was returned in kind too. On the outbreak of the 1857 revolt in Bihar, a delegation of priests from Vishnupad temple waited on the Gaya district magistrate, Alonzo Money, and offered of 3,000 lathials (club-men) who would defend the Englishmen, their families, treasuries and government properties in that engulfing crises. Money immediately communicated the novel initiative to the Government of Bengal, Calcutta. Dabbling in politics, thus, has hardly been an unknown phenomenon among temple priests in the country over the ages.

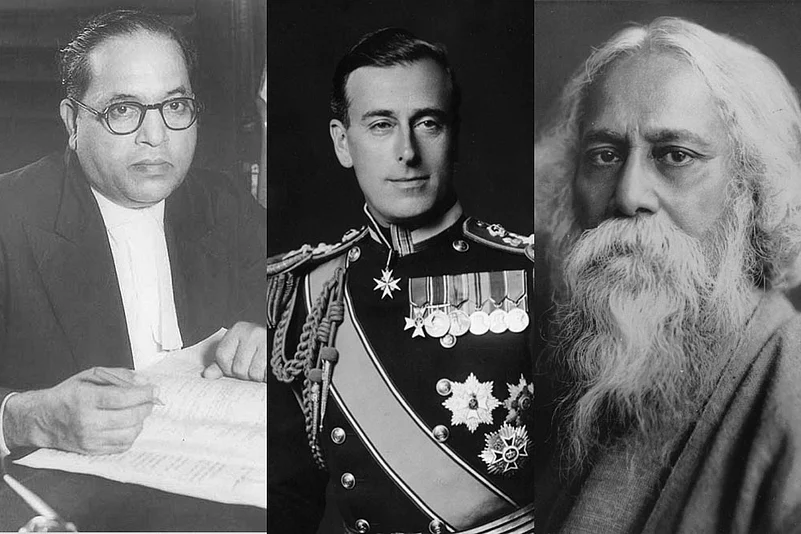

Ambedkar was denied entry into the Puri temple, while Lord Mountbatten was welcomed; Tagore’s clan too was barred entry during 1809-10

Madhu Dandavate, who was railway minister in the government headed by Morarji Desai and finance minister under V.P. Singh, while deposing before the Backward Classes Commission with B.P. Mandal as chairman, stated that Lord Mountbatten, accompanied by Dr B.R. Ambedkar, the Governor-General’s executive council member, visited the Jagannath temple once. The British Paramount was accorded a red carpet reception by the Jagannath temple, while Dr Ambedkar was denied entry.

Was Mountbatten a vegetarian? Did he not prefer beef as his staple diet? Then what leg do they have to stand on, this section of the servants of Jagannath who denounced the West Bengal chief minister, who has only defended the freedom of dietary choice for the people of India?

(The writer is a retired IAS officer and former vice-chancellor, B.R. Ambedkar University, Muzaffarpur, Bihar.)