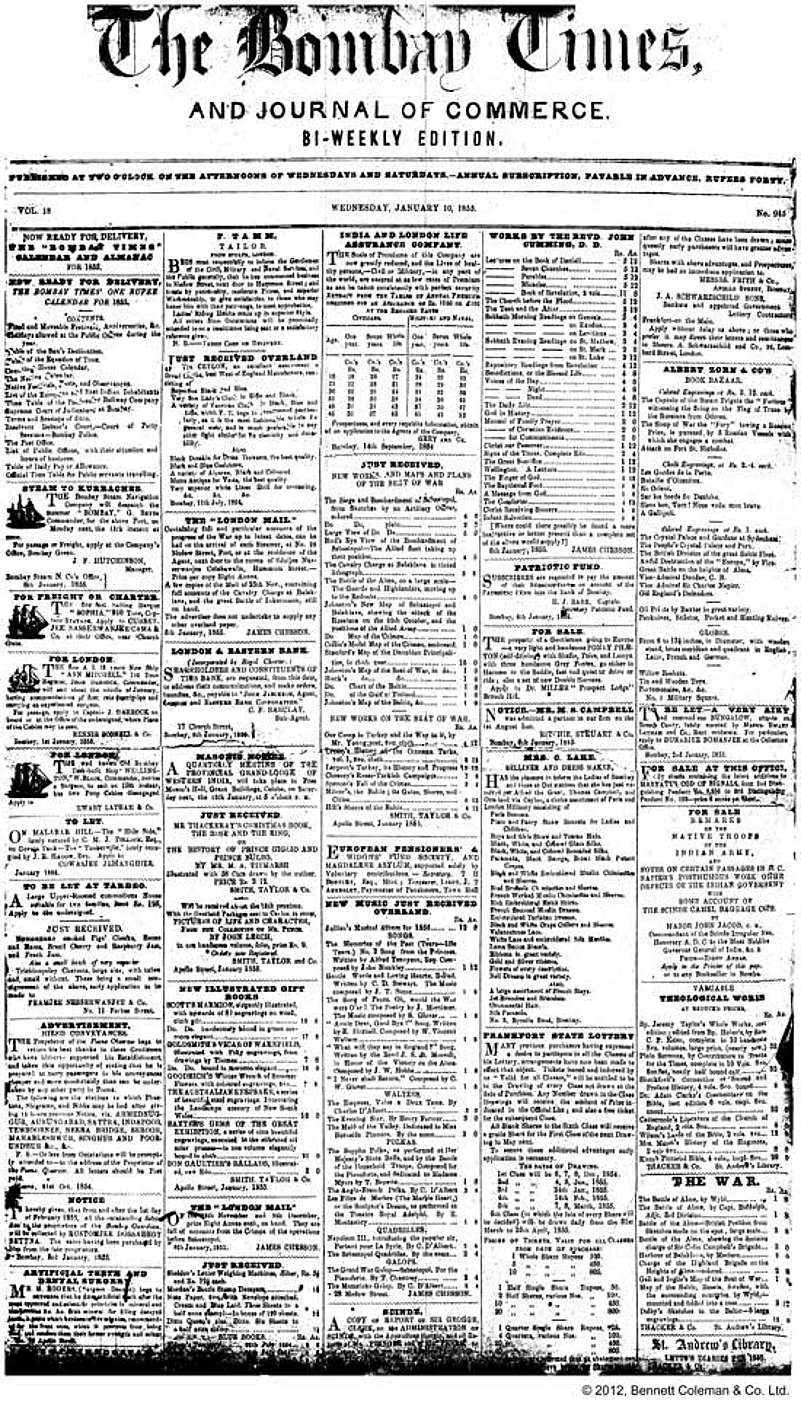

In 1855, at the age of seventeen, The Times of India was not yet known by that name, which it acquired only six years later—on May 18, 1861, when The Bombay Times and Journal of Commerce, established on November 3, 1838, merged with two other local publications. Historians of the press have quibbled about the paper’s exact date of birth. However, in a country that takes reincarnation with utmost seriousness and regards all avatars worthy of equal respect, it is small wonder that the paper itself has preferred to stick to the date of its genesis.

Another factor, a decidedly mundane one, explains why The Times of India is well within its rights to declare 1838 as the year that marked the beginning of its remarkable trajectory. What provided both an editorial and managerial continuity between The Bombay Times and Journal of Commerce and The Times of India is the endeavour of one individual, Robert Knight, one of the most inspiring figures in Indian journalism during the 19th century.

.jpg?w=801&auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&format=webp&dpr=1.0)

| Times’s e-paper |

His views were pointedly against the conceits and arrogance of the Raj establishment. This persuaded the proprietors of The Bombay Times and Journal of Commerce to appoint him as the acting editor of the paper when the editor, George Buist, proceeded on home leave. This was in 1857. The owners were delighted when Knight wasted no time to demonstrate his independence of mind in his assignment, just as he had done in his celebrated freelance articles.

Through his sharply worded editorials, Knight campaigned for a sound system of popular rights in India and sought massive investments to extend the rail network, improve Bombay’s water supply, construct roads and set up irrigation facilities. He continued to upbraid British officials for the perks they enjoyed, for their nastiness towards Indians and for doing precious little to eradicate India’s abysmal poverty. Moreover, unlike the rest of the Anglo-Indian press, he sympathised with the Great Uprising of 1857 even while he deplored the large-scale destruction of lives and property.

Alarmed by the turn of events, Buist cut short his vacation in England and rushed back to resume charge of the paper. Overnight, he reversed Knight’s liberal editorial line, to the utter chagrin of the main shareholders. Led by Fardoonji Naoroji, an eminent Parsi businessman, they urged Buist to rein in his exuberantly pro-establishment stance. When they drew a blank, they again turned to Knight and, to take no further chances, confirmed him as the paper’s full-fledged editor.

True to style, Knight spared no words to criticise the greed and mismanagement of the British authorities, their policy of annexing native lands, their arbitrary and unjust tax regime and the type of education they sought to impose on Indians without showing the slightest regard for their needs and customs. As the founder-editor of The Times of India, he lambasted missionaries for their aggressive efforts to convert Indians to Christianity through force and inducement—this, even though he was a devout Christian himself. Likewise, he made no secret of his dislike for traditional Indian religious beliefs and practices and held the caste system in particular in contempt. But he also warned the colonial regime not to resort to methods of coercion to set right these wrongs.

In the eyes of the colonial rulers, Knight appeared to be no more than a sycophant intent on keeping his Indian bosses in good humour. But, as Edwin Hirschmann points out in his excellent biography, the great editor’s moral outrage was rooted in his experiences as a social outsider. These inculcated in him an “ingrained sympathy for the disadvantaged and disgust for the duplicities of British rule”. The biographer adds that during his seven years at the helm of the paper’s editorial team, Knight had built a “vigorous, thoughtful and conscientious newspaper which had stirred Bombay and its governing authorities”.

The seeds that Robert Knight planted, around when the forerunner of The Times of India turned seventeen in 1855, today stands as a tall and sturdy tree, its branches and foliage spread across the length and breadth of India—and beyond. A good occasion for the paper to salute the legacy of Robert Knight, and to reiterate its commitment to it, is round the corner, in 2013, when it celebrates 175 years of its existence.

The author was editor of The Times of India from 1988-94, and is now its consulting editor