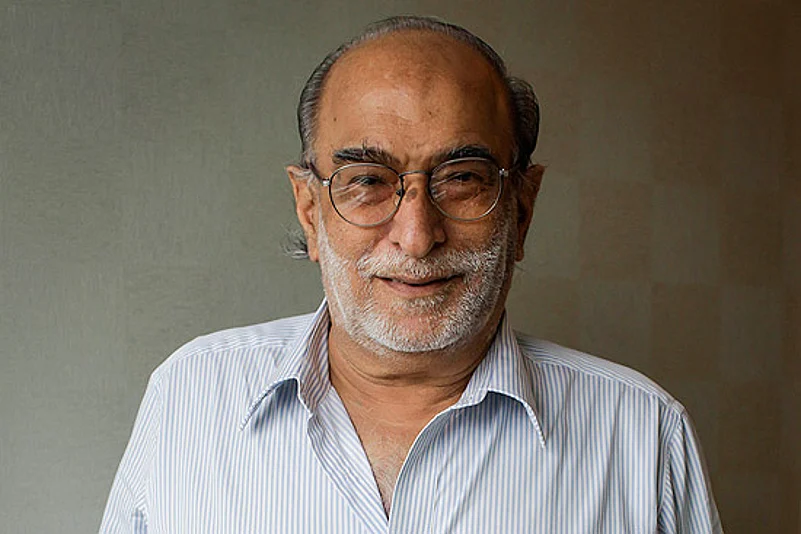

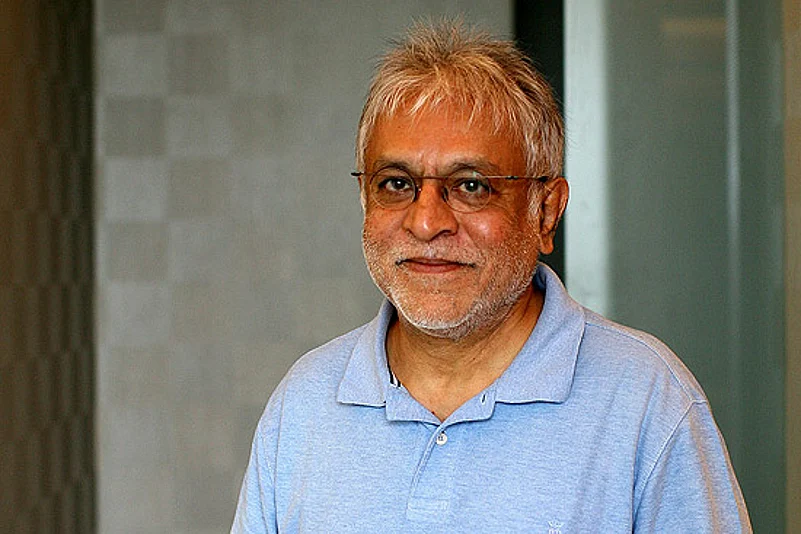

To discuss magazines and their future, Outlook organised a freewheeling roundtable discussion in Mumbai. The participants were Ashok Advani, publisher of Business India and a veteran in the genre; Naresh Fernandes, former editor of Time Out and founder of Scroll.in; Aurobind Patel, design guru who worked with India Today and the Economist magazine; and Shobhaa De who edited and launched three magazines—Stardust, Society and Celebrity. De fell ill just before the event and added her contribution later. Also present was Outlook’s Mumbai correspondent Prachi Pinglay-Plumber. The roundtable was moderated by executive editor Dilip Bobb. Excerpts:

Bobb: Welcome to all of you. If we flashback to 2008, when the global economy went into a tailspin, and one of the early victims was the print media. There were dire predictions about the death of magazines. We are now in 2015 and many of them are still around, some are doing well, some not so well. So we are really looking at how we see the role of the magazine, the future, a lot of great magazines are still surviving.

Advani: And thriving.

Fernandes: Are you sure?

Advani: I think two things are emerging quite clearly. One, I would say that there are very few purely online properties in the news space or a magazine space that have succeeded. Those people who are successful have combined a print plus online model. The revenues lost in print are partly made up online, the audiences lost in print are partly made up online. Let me put it this way, there are people who read, sometimes print, sometimes online, depending on their leisure, depending on where they are, on their moods. And therefore I think the division that has been there in people’s mind here in India, in the last year or two, is slowly going to disappear, and people are going to realise there is space for both. That’s the way I see it.

De: There will always be space for magazine journalism! Always! Some may fall by the wayside. Others may try and reinvent. But a strong format with a loyal readership is hard to dislodge.

Bobb: Naresh, is there something about the look and feel of magazines which is so different from online content that still makes them relevant in today’s world?

Fernandes: I am going to keep the business part aside. I do agree that people now read in a sort of a seamless way, so you pick up a magazine when you are home in the morning, when you are in the train in the afternoon. And in Mumbai you see this all the time—people are using big devices in the train and reading all sorts of things. So this is just a question of how you become available. And so a lot of people have spoken about it as the death of print. I think that is exaggerated, I think people just want to read in a convenient way and so that’s what online represents. In terms of the magazines itself, we at Scroll invoke the term magazine every day to mean contextualisation, to mean a certain sophistication in the writing, to mean a way you think about the world, to mean a permanence in the way a story is presented. And so, yeah, the magazine definitely has its role, I think, the medium in which perhaps its article is presented will change, but the format of the magazine is very relevant.

De: Some standalone magazines are designed for dentists and doctors. But there is nothing to beat the experience of holding an exquisitely produced, supremely well-written magazine in one’s hand. I like flipping pages. I like the touch of a glossy. A ‘combo-meal’ seems to be the answer.

Bobb: Aurobind, you know all about magazine formats and design, what has changed, or needs to change?

Patel: Technology has made a huge difference. For instance, if I want to look at an architectural magazine, today we can walk through the pages, the things that you can do with the new technology, which you could never do in a static publication. So I think that there are certain key advantages that technology brings to design, which are vastly impressive. And they can be used very effectively.

Bobb: So will magazines be competing with online sites or will online news sites become more like magazines?

Fernandes: When we were thinking about what we wanted to do when we were doing Scroll, first we thought maybe we will do this single strand of thing. You know, have one long form piece maybe if we can get in one maybe in two weeks. And then we realised that actually that is not appealing. You don’t build a loyalty. And, so we realised that the magazine, we keep coming back to the magazine because there are all sorts of cliches, you know, it is like the thaali, you get lots of different flavours and that’s what your meal is about. You don’t want only one flavour all the time, one dish all the time. And so what we are trying to do essentially, and this is what we tell our writers, is that we want to have the urgency of a news wire but the sophistication of a magazine piece.

De: Somehow, I cannot connect to any of them with the longer formats. It’s a generation thing. I like getting news capsules on these platforms. But I vastly prefer taking a magazine rather than a tablet to bed.

Bobb: Everybody here has grown up on magazines. Some have started them, some have worked for them. But in terms of the role that print magazines are playing in the media space, in terms of readers, in terms of what we provide that is different from what we get from newspapers, from the online space, these 140 characters on Twitter and this hysteria on television every night. How do magazines compete?

Advani: In the 35 years that I have been following this, I haven’t seen such a slowdown in terms of cuts in corporate spending, therefore obviously advertising gets hit. Having said that, obviously everyone is influenced by the huge amounts of money that internet properties have raised. Although primarily they have been these e-commerce sites rather than necessarily editorial-driven sites, the fact is that the internet and online is the buzz. And, therefore even in the mind of the advertisers many people are saying, well, is the audience we want shifting online, are newspapers relevant, are magazines relevant? Having said that, particularly in the case of the lifestyle magazines, there is no doubt that online doesn’t succeed, and there is no way you can get the look and feel of homes, clothes, call it what you want, in the glossy lifestyle magazines, you cannot get that online. And people seem to want to look through these magazines at leisure and there is a look and feel to them that is not just replicated. So in fact some of the magazines that have been doing well today are still the lifestyle magazines.

De: These magazines sell every square centimetre. That’s how they survive. There’s no space left that doesn’t come with a price tag. Readers either don’t notice or don’t care. Ground events make up most of the revenues.

Patel: Absolutely, yeah. I think in my view magazines will have to be much more analytical, much more thought-provoking, which is easier to do in print than to do it in short bursts on the internet.

Advani: There is the same argument going on within the internet also as to whether you need long-form pieces or you need shorter pieces. And clearly there are successful examples of shorter pieces catching on quite dramatically. But it is much more difficult I think to do analysis, to do charts, to do tables, to look at family trees, on the net than you might find in print.

Patel: Actually I might disagree with that, particularly when it comes to charts or even family trees for example because you can actually build it. Instead of showing the whole thing at once you start the father married so and so, so you can actually see it evolve, so there are ways of doing it and then you see, because the thing with the graphic is that it is frozen, it is all there and then you make sense of it. But if I were building a pyre, I am suddenly seeing the thing as it evolves.

Fernandes: I will also disagree with your contention about length. There is a stereotype that things are shorter on the web. So, for instance, every Scroll piece runs at a tabular of a 1,200-1,800-word article, which is often longer than most magazine pieces. People are bringing all sorts of complex sophisticated things online and so I don’t think there is any form that particularly works better on the internet. It is just how well a piece is written.

Advani: Also, now every newspaper wants to become more magazine-like in terms of features and analysis, etc.

Fernandes: That is the difference, I think the big change that magazines brought about was a change in newspapers.

Patel: Look at their supplements, the supplements are nothing but a magazine.

Bobb: Yeah, your weekend paper is strictly a magazine, and we are seeing more and more features, more long-form journalism.

Fernandes: Could it be that newspapers are fighting the supremacy of television?

Advani: Yes. Magazines have a different time scale with which they have evolved.

Bobb: So you think newspapers could fight more effectively if they were to take lessons from magazines rather than from television news?

Patel: Yes, absolutely.

De: Magazines are obliged to be good-looking. Period.

Bobb: For magazines, the obvious touchstones are The Economist and The New Yorker. There is only one New Yorker in the world, there is only one Economist, but it takes an enormous amount of talent to bring out magazines that have been consistently successful.

Patel: The Economist model is talent, purely talent, it is unbelievable.

Advani: Talent has to be backed by a business model, so it is a combination of these two things.

De: The only way to survive is to sell every page!!!!

Bobb: The Economist has not changed much over the years, neither has The New Yorker. They both focus largely on the print version. How do you really see old-school journalism, long-form journalism, doing in this digital age?

Fernandes: This long-form thing drives me bananas. I don’t see what for, but people have begun to obsess about the length rather than the content. Every day I receive 10 queries from young people who want to go to Madhya Pradesh and write about things like some old lady under a mango tree. They write the story and they never get to tell me why this old lady is wailing under the mango tree until four pages later. And so they get obsessed by this sort of literary form rather than the nature to tell the news in the appropriate way. The thing about the magazine is that it was a different kind of technology and so you deliver once a week. Now you can deliver a magazine story through the week, as we try to do once or twice a day. So the news values and the craft value of the magazine story, I think, would remain. The platform I think is what’s changed.

Pinglay-Plumber: I would say from personal experience and people I know that you go to the net for that news update. You are not going there for their indepth pieces. Is that changing? I mean that’s what magazines do compared to you.

Fernandes: I think that people think they have come to the net for a quick burst and so people always tell me you write lovely short pieces when it is actually 1,500 words. I think it is just that you don’t realise how long it is. I think people are also reading very long things on the internet. They don’t realise how long it is. They read the same piece in print, so I don’t think it is to do with the medium, it is just to do with craft of the story and the story-telling.

Patel: On the presentational aspect, what’s happening in the last few years is the font and design, you can actually have very good-looking things on the net, once your phone resolutions have gone up. You get outstanding typography. So you can actually continue that feeling of being familiar with something like a New Yorker when you are reading it online, which, you know, 10 years ago when you were on the net you only saw Times Roman or Arial. Also in order to buy a magazine subscription for the New Yorker, you have to have access to all these various mediums. New Yorker, for instance, will give you daily briefs, though it is a weekly magazine, depending on your interest, it will give you stuff saying, this might interest you, which I find is quite fascinating.

Advani: I think we should talk about the fact that audiences are changing very rapidly. I mean when you were 25 or 27 if you told somebody you never bought a newspaper, you never read newspapers, you would shock people. But today most kids quite happily say they don’t buy newspapers at all, they don’t buy magazines and they get everything today off the net. I think the niche of the audience is changing very, very fast and I am not sure whether you got the leaning of our audiences right, it is a big issue on my mind as to what the nature of the audience is.

Fernandes: And how to keep them hooked.

Advani: They say content is king and all that. I prefer magazines compared to the internet which as you know, is largely anonymous, or your television which is a shouting match where nothing of substance really emerges. So, domain expertise, for instance. Great magazines have produced great writers and people will read what this person says. So magazines have that advantage that you have that person who is a name which is not so much visible on television or the internet.

De: I remain an incorrigible magazine junkie. I cannot walk past a magazine (regardless of the language it might be in) without picking it up and checking its contents.

Patel: I completely agree because again I am going back to the example of The New Yorker or The Economist. The reason why they are what they are is that they are so enshrined in their core values, you know, of just good writing. In the case of New Yorker, outstanding cartoons, they are brilliant. So it is just that they have stuck to it, and to believe what we stand for when we stick to it. And then I guess we survive the changes. And then you make appropriate changes for the times you existed. You don’t write something that is irrelevant. And then I think you will always have a following.

Bobb: There is an argument that the major issues and concerns of our times are extremely complex and challenging, multi-layered, multinational, with many shades of grey. Does that make the magazine the best platform to examine such issues?

De: Not unless you happen to be The Economist. The rest don’t count. Weekend supplements are good enough.

Bobb: The Economist is known for taking a stand for strong views. Is that the way to go for magazines, to have strong opinions?

Advani: And some agree, some don’t.

Advani: If you go back, go back a 100 years and see the big journalists who really made their name, they were all called editors not for nothing, they all had strong views. And that’s what made news empires.

Patel: In The Economist, I think the process has been so institutionalised by the adherence to core values, so the people that edit it have a certain commitment to those values and they keep it going along those lines. So I guess it is like-minded people, opinionated people who keep it going.

Advani: In the Indian example, the modern Indian press, much of it came out of the freedom movement and therefore was strongly partisan. And then magazines had their boom in the generation that came of age during the Emergency, and therefore saw themselves as questioning power. So it is not as if these were exactly neutral....

Bobb: Today, there seems to be a trend to hav columnists who you know are going to take a strong opinion, a strong stand. This is true of both newsmagazines and online news sites.

Fernandes: The battle between newsmagazines and internet is so vexing. My colleague, Supriya Sharma, in an issue of the Caravan, wrote a very meditative piece last year, just before the Lok Sabha elections. She got on to a train, travelled 2,500 miles between Assam and Kashmir for three months. She also did a series of reports almost every day, talking to people about life and politics, excellent series. And then she came back and about a week later there was this scandal that broke on the Internet about Digvijay Singh and his fiancee, now his wife, and she did a small piece, maybe 500 words, on the woman’s right to privacy. And she said that she got more hits on this one opinion piece in a day than she had got for three months of work. You know, in the end, as editors we decide the mix and you know, you could sort of do a quick opinion on them and I don’t think it adds up to any amount of credibility for the publication. And in the long run I think that will prove to be ineffective.

Bobb: Ashok, as you know, where everybody is trying to innovate to get new readers, in terms of say business magazines, things have changed extremely fast. Is there a new thinking, a new way of presenting business news that appeals to what they call a younger reader?

Fernandes: Online, yeah, much more difficult to get it online when it is paid for or not. I think the obvious model is a combination of print and online presence, you know in terms of designs and appealing to the new reader who already has one of the gadgets which can access the same amount of information.

Advani: The other thing I’d like to say is all of us here, you know, started at a time when the media was much more static and there was much less competition. One of the things that has happened today is fragmentation of audiences so you will have eight business magazines, you will have 20 political magazines and you will have 15 insurance magazines, therefore the audience gets fragmented much faster than people imagined. It is, and also the same with newspapers, or with websites for that matter, so many websites, there is a fragmentation of audiences. And everyone, whether you are a newspaper, magazine or a website has to rethink its economics as to how are they going to deal with this huge issue of competition from multiple sources.

Fernandes: I believe the nature of the web is it is not either/or, so people would read Business India and BusinessWorld and Economic Times and this is the thing about getting stuff free. You know, you read much more than you did before. And so I think everybody has really benefited from an enormous expansion of audiences. Of course how you monetise, that is something we have been trying to crack for 20 years.

Bobb: You know, all can’t monetise it, some people are going to succeed, some won’t. Every publication has a digital version now, but newspapers are a habit. You wake up in the morning, you open it, you read it, you don’t want to go to your phone to read the newspaper. Does that apply to magazines that are a weekly or a fortnightly? Is that a habit which will help in magazines surviving that you have leisure time and you pour yourself a coffee or a glass of wine and you open a magazine like you do with the newspaper in the morning?

Patel: In the digital realm, I subscribe to The New Yorker and I can go back to the last six weeks or six months if I want, it’s on my iPad. So yeah, in that sense it is like going to a dentist’s and reading through old magazines.

Bobb: But you know, the problem is with the new generation of readers at least. You can subscribe, but if you want it free, somebody will give you access to some of it, somebody will charge you if you want to read the rest of the article or you want to read half of it. So everybody is playing with this model and nobody has figured out really, you know, how far you can go and how much free you can be because why would anyone, you know, buy your print publication.

De: Publishers must forget this battle and give up! It’s a no-win situation. Youngsters don’t read. It’s that basic.

Patel: What’s interesting is that content is being tailored for specific devices, and that will impact audiences. Fifteen or 20 years ago, the internet or internet on phone had not happened. Now anyone who is designing is looking at liquid or flexible designs that are kind of amenable to the media on which they are going to be served, so you don’t think of an ideal web page on a screen any more. All designs are thought of as very malleable liquid things that actually respond to the device on which they are going to be displayed.

Fernandes: And that’s completely different from how it will be in a few months from now.

Patel: It is to do with evolution and technology. Before if I did a website, I could only deliver it the way I did it on the screen and I couldn’t do it two different ways. But now coding and all allow you to do that, allows me to query the device I am delivering it to, and then deliver it appropriately for that device.

Advani: The net is going through an evolution. The truth is even Amazon is losing money today 20 years on, so there are people who are willing to bet very long, very large sums of money, long term, all the winners, all the possible winners. So we are still going through a phase where we don’t know who the winners are, and therefore it makes it much more difficult when there are people willing to give it away free in the hope they monetise it some time later. Actually print is already giving it away for free, at `2 for your newspaper you are giving it away for free because your production cost is much higher.

Fernandes: But I wouldn’t trust in subsidising, when you have given the reader stuff for free, you have created this notion that this is not worth very much. Most magazines are subsidising their readers.

Advani: No, all magazines have raised their prices. The cover price of your newspaper or your print publication is barely covering the cost.

Fernandes: On the web, there’s a marginal cost to reach another hundred readers. You are spending so much on distribution in a way that we can now reach two-and-a-half million readers without any of your magazine distribution costs. So we are probably ahead of the game but we are like everybody else who claim that they have a working module which actually doesn’t work.

Bobb: Yes, but you look at the great magazines, The New Yorker, Economist, Atlantic, Harper’s, Wired, they have all survived and hopefully will thrive and you know, they have a digital version, but you look at their print version, it hasn’t changed all that much.

Advani: I want to go back to what you know, people are always asking us what are you doing new. And I say we are not doing anything new, we are doing old. I think newspapers and some magazines lost the core values of journalism and we see ourselves going back to where we were 25 years ago, the values of reporting, of checking things, great writing.

Fernandes: And that is clearly what the readers want.

Advani: Exactly.

Bobb: Shobhaa, if you were to be convinced to return to the role of editor of a weekly publication, what are the mantras you would follow to keep readers interested and engaged?

De: I may be seen as being bold and gutsy on other fronts. But even I won’t be reckless enough to commit harakiri. I’ll pass, thank you!

Pinglay-Plumber: You know the internet, it is much easier to track your audiences, like how many hits, when it comes to magazines, how does one really estimate?

Advani: Subscribers. The subscription ones are easy to measure, news-stands you don’t know.

Pinglay-Plumber: So does that become difficult when it comes to going to the advertisers because online medium will give you, we have x number of hits in x number of minutes or hours, you know, vis-a-vis a magazine.

Fernandes: Actually, the people who are hit the most are TV because nobody knows who is watching those ads. I mean they are broadcasting whether somebody is in the room, not in the room, which family member is in the room, nobody knows. Even the most sophisticated tracking device can’t tell you much.

Advani: Television is the most expensive advertising.

Fernandes: The truth is that many ad agencies, if you ask them honestly, they say we don’t know where we are spending our money or how effective it is. So I think television is hurt worse than print in that sense in terms of tracking and measurement. And certainly from what I can see elsewhere, overseas, the big argument seems to be the internet versus television now.

Pinglay-Plumber: It has now also become completely multimedia, right, you have a written report, a video, an audio, everything is on your mobile, it will have your long form it will have the photo gallery, all of it. So that really makes it difficult for any other media, isn’t it?

Advani: That presupposes people have all the time in the world to go through all this.

Bobb: Also issues of connectivity and the bandwidth to access all this.

Patel: All that will presumably change with 4G.

Fernandes: And a whole heap of canned media because they are going to get a lot of media on it.

Pinglay-Plumber: At what price?

Advani: `900 a month, so I’ve been told by Reliance. That includes staggering speeds, virtual access to most TV channels.

Bobb: For the ones they have already bought.

Advani: Exactly.

Bobb: Back to magazines, so are we more or less agreed there are problems, there are financial issues involved, advertising is shrinking, but that applies across the board. If we look at this dual online and print version, you are satisfying a dual need. So are we saying magazines are still going to be around for the foreseeable future?

Advani: I’d say so, but I’d like to add one caveat also. I think like in any other business, the market cannot sustain more than 2-3-4 players. To have eight English newspapers in Bombay or Delhi is unrealistic. So there is going to be that consolidation or shakeout. Again, can you have eight business magazines surviving? Surely not, you can have 2 or 3 or 4. And I think the same thing, the same economics, would apply to magazines. It is like any other business. Can you have 12 cellular companies in India? Probably not. Can you have 25 cement companies? No, it will be a shakeout and that is constantly taking place, not just in India. I mean can Europe afford 14 car companies? So the normal rules of the economics in business will apply, and therefore....

De: Magazines can survive by standing out. By offering something seductive and new.

Bobb: Meaning the best will survive.

Advani: Yeah, I mean, when I said it is a shakeout, the ones that are producing quality content will survive, and some will even thrive.

Bobb: Which is a good note to end on.