It’s an inconspicuous little one-storey dot in a largely peaceful, middle-class neighbourhood in Tamil Nadu’s Viralimalai, a stone’s throw away from the glitzier airport city of Trichy. The walls are cement-washed—sturdy, yet reeking of an antiquity buried under layers of consolidating, mundane grey. The unceremonious clamour of utensils echoes through the backyard (that doubles up as a bath) and right into the humble home of a past that remains mostly forgotten. An old woman in a plain cotton sari trundles back in after spitting out a mouthful of paan outside her door. “My leg has been hurting for a while,” her eyes flinch a little in pain, adding a few lines to the ripples on her skin left by time—80 years to be precise, all spent trying to salvage an art that defines her legacy, and India’s too. Even if India doesn’t know it.

Just last year, R. Muthukkannammal was invited to conduct a workshop on Sadir near Chennai. Sadir...what?...do I hear you ask? The word sounds almost alien to a nation propped up on feet relentlessly practising Bharatanatyam, or the “Dance of India”, for decades, among other classical forms—none sounding remotely like Sadir. But rummage through pre-Independent India’s yellowing archives, and one might stumble upon this word. It belonged to a land quite different from what the British left behind, and a time whose rhythm was set by feet dancing on temple stone—the feet and bodies and minds of Devadasis, the custodians of Chinnamelam, alternately known as Dasi attam or Sadir, whose ghost now lives in its distilled and ‘purified’ incarnation as Bharatanatyam.

Muthukkannammal is the last fruit of that original tree.

The Devadasis of the south, and Maharis in Odisha, were demonised and outlawed by the British, in line with the Victorian morality that still governs our laws and social attitudes. Nor did Independence bring freedom from that obscurity and shame—the stigma pretty much informed the new canvas of ‘pure’ culture painted in Nehru’s India. The old female custodians retreated to the bottom layers of the palimpsest, still seen as corrupt, sexually deviant beings to be ostracised. But the old world still shines through Muthukkannammal’s sharp words and glittering eyes. “I would be up by 3.30 am every day to rehearse. I was in a family full of dancers, who woke up even earlier to practise,” she says, as her school-going great-granddaughters come running for a hug.

Muthukkannammal accidentally found herself in the spotlight after spending years in relative oblivion when DakshinaChitra, a cultural forum, opened its doors to her, conferring her with a cash award on learning about her meagre livelihood. “I am one of the 32 Devadasis of Viralimalai, from the period of Maharaja Rajagopala Thondaiman. My father, Ramachandran, was my guru…he also trained me in music. You see, unlike Bharatanatyam, we have to continue singing while dancing. Bharatanatyam has emulated our dance and become popular,” she says. Ruing the lack of official patronage, she says, “As the only surviving practitioner, I am scared that the history of my mothers, the Devadasis, will be wiped out in my absence.”

Without patrons, any form of art suffers. For Indian dances, British dominion uprooted the entire ecosystem of patronage, squeezing dry the treasuries of all kingdoms that funded temple and court performers. The attack on the arts, however, went deeper—it was fundamentally moral. The British condemned the dances by linking them to prostitution and debauchery. Sample civil servant William Hunter’s words in the 1878 Bengal District Gazetteer, after he apparently watched a performance at the Jagannath Temple in Puri: “Indecent ceremonies disgraced the ritual, and dancing girls with rolling eyes put the modest worshipper to the blush.… The baser features of a worship that aims at a sensual realisation of God appears in a band of prostitutes who sing before the image.… In the pillared halls, a choir of dancing girls enlivens the idols’ repast by their airy gyrations. The indecent rites that have crept into Vishnuvism are represented by the Birth Festival (Janam), in which a priest takes the part of the father and a dancing girl that of the mother of Jagannath, and the ceremony of his nativity is performed….” This is one of many such colonial-era reports—words that slowly corroded the bedrock of India’s classical dances, covering their delicate aesthetics in a cloak of moral horror.

“We barely find representation in official bodies or festivals,” says Gaudiya Nritya practitioner Banani Chakraborty

What of the charge itself? Well, it was not right or wrong in a bald factual way as much as a cultural miscognition. In a male-ordered world, gender politics is decidedly unequal, but this old world was one in which sexuality had a life-affirming status. And ironically, the British projection of temple dancers as prostitutes became a cruel, self-fulfilling prophecy. “As a people, we did not have the kind of shame around sexuality our colonial masters did,” says Odissi exponent and scholar Ananya Chatterjea. “We certainly had patriarchal contexts in which these dances existed, but the dancers were constantly navigating a complex force-field to find space for their work. When these dances were re-situated, in re-choreographed form, onto proscenium stages, we made them in effect hold space for middle- and upper-class women who could speak for the ‘nation’ and its long stream of ‘tradition’. What you are speaking to are the ravages of that history.”

Indeed, the British made it impossible for these dancers to find space in Hindu society, which too started to stigmatise them as corrupt temptresses, and they were left with no room but that to scavenge for food and money. From being at the centre of power structures, vested with bearing the spiritual burden of the kingdoms, the Devadasis and Maharis were now thrust to the abhorred peripheries.

Their art, naturally, withered. In the new aesthetic regime, sensuality or ‘eros’ (sringara rasa in Natyashastra terms) had been rendered morally dubious. The victims, expectedly, were women; male practitioners remained largely insulated, though forms of fluid sexuality flowed as much from their dance. “It was a gender-biased campaign, largely driven by Christian missionaries. It only forbade women dancers. Male performers flourished as custodians of art and became the ustads. I feel this is the most criminal thing we did to the brilliant women performers of the 19th century,” says Manjari Chaturvedi, Lucknow-based Kathak practitioner.

Chaturvedi’s long-standing mission has been to revive the dance of the Tawaifs, or the “fallen women” whose progeny still face brutal rejection. The recreation of the old, intimate performances involves careful study of surviving gramophone records of songs, movements depicted in paintings and literary descriptions by 20th-century scholars. Chaturvedi’s reading of the misogynistic onslaught the colonial state unleashed on India’s dances corroborates the erosion, or conscious mutation, of the three older, majorly female, precursors of the modern-day ‘classical’ forms—Bharatanatyam, Odissi and Kathak.

‘Epidemic’ of Dance

This was a kind of cultural genocide. Like the Devadasis and Maharis, the project to ‘eradicate’ the social epidemic of dancing girls also hit the Muslim Tawaifs of the north and the Baijis of Bengal. The social upheaval of 1857 did not spare their kothas: the British seized their lands and ordained them to society’s darkest recesses. An ‘anti-nautch’ campaign in the late 1800s aimed to decimate ‘nautch girls’, a collective term for temple and court dancers. In 1890, a missionary called Rev J. Murdoch launched a full-blown print campaign against ‘nautch parties’. He called upon British officials to not be witnesses to amoral acts of seduction. India was soon flooded by such campaigns, the Madras Christian Literature Society being single-handedly responsible for a large percentage of anti-nautch literature. Earlier British officials had slipped into the same congenial relationship that India’s feudal lords had with the dancers, but the practice of inviting Tawaifs and Baijis to entertain visiting British dignitaries soon gave way to ballroom dances. The air of shame was infectious, and local sources of sustenance also started drying up. The Bai-Nautch of Bengal also started to lose its feudal patrons, now influenced by the Brahmo Samaj. Court dancers sought to survive by shifting from their older patrons to the nouveau riche, but the suffocating air of ‘ethical cleansing’ now infected even the new bourgeois classes.

As the walls of the kothas started to close in on the female practitioners of Kathak, the venerated temples of Odisha began to exorcise Mahari, a dance-form that modern-day Odissi heavily borrows from. “Odissi is for commoners, Mahari is only for Lord Jagannath,” says Rupashree Mahapatra, the sole practitioner of the age-old dance. Rupashree practises and conducts her dance lessons in the same room that houses her miniature Jagannath temple. The home of her in-laws in the beach town of Puri is a crumbling 200-year-old relic, held together by the embracing arms of wise, old banyan trees, as old as humanity. A creeper artfully manoeuvres its way through a gap on the wall between Lord Jagannath’s portrait and a photo of her guru, the last-known Mahari Sashimani, who passed away in 2014, aged 93.

“After I got gold medals in Odissi from four universities, I aspired to do something more,” says Rupashree, Sashimani’s adopted daughter—a custom followed by temple dancers to perpetuate their legacy as a result of being married off to male Hindu deities at a young age. Now in her 40s, she seems to slip into a trance as her body lilts to the tunes of Geet-Gobindo playing in the background. She bends ever so slightly, as if delicately balanced on a spring, a far cry from the heavy circular motions of Odissi. To one accustomed to the latter form, what leaps to the eye in Mahari is the tremendous emphasis on bhaav or expressions—the eyes have it, and the subtle twitch of the lips, almost betraying a smile reserved only for her lover, the Lord. The equation here is decidedly different. “I hope I’m born a woman in every life so I can dance for Jagannath. Why should one do so much kasrat to express, like in Odissi or Bharatanatyam? A little bhaav is good enough. These are like conversations with your partner, intimate and beautiful. We dress in gold jewellery, a sari, and do elaborate make-up, with emphasis on our eyes. I feel I completely transform from within when I dance for Jagannath. It’s like an out-of-body experience,” Rupashree explains.

Visually, Mahari seems to be set on a pole diametrically opposite to that of Odissi. The latter has embraced a two-part top and dhoti trousers made of the local Ikkat or Kotki with minimal silver jewellery; Mahari goes all out in red and yellow saris and gold ornaments—39 pieces as we counted, with an elaborate headgear and, yes, make-up. It’s sringara, after all. Much like Bharatanatyam/Sadir, the proponents of Odissi wish to have nothing to do with its mother form and its contested history. “The big practitioners create disruptions. Unless they let go their ego, it’s impossible for this tradition to survive. How much can one person do? We really need more help from the government and the Sangeet Natak Akademi,” says Rupashree, the sole flag-bearer of Mahari after Sashimani’s death, a tragic milestone in India’s cultural history that no one even noticed.

In many ways, colonial and post-colonial India carried the hearse together. The final leg of the cleansing process began in 1934 with the Bombay Devadasi Protection Act, which ‘protected the interests’ of Devadasis by lawfully recognising their marriage to a man and their children born out of wedlock. The dedication of a Devadasi to a deity was made illegal; any third person involved in it would henceforth invite a jail term. Unfortunately, what the rehabilitative law safeguarded was not the ‘interests’ of the dancers; nor did it have anything to do with their craft. The Madrasi Devadasi Act of 1947, originally floated by Muthulakshmi Reddi, the first woman legislator in British India, followed the one in 1934 and finally by 1988, the practice of Devadasi dance was completely outlawed in India. This final nail in the coffin of the ancient, erotic dances sealed a cultural ‘renascence’ on the lines of a Hindu spiritual realignment of the forms, whose core emotion would now change to bhakti.

The Asexual Nation

As Indian leaders internalised the European concept of ‘nationalism’, based on Enlightenment ideals, India’s art forms were reformulated to fit the new identity of Brand Bharat. An explicitly shared heritage was necessary for this, and thus the various ‘classical’ dances were herded, catalogued and certified, Kathak exponent and social anthropologist Pallabi Chakravorty writes in her essay. This ‘renovation’ of heritage had two broad, specific conditions: 1) cleansing the dance forms of their erotic traits, modifying the movements from the sensual to the sublime and spiritual 2) reinventing the history of the dances on a predominantly “Hindu” philosophy, consonant with the tacit ethos of nation-building. This purging was a sine qua non for new India to have an ancient, untainted ‘classical’ culture. The spirit was oriented towards saving the “nautch” (in purified form), but not the “nautch-girls”.

Chhau is not recognised as a classical dance form despite being among the oldest and most codified, with three distinct strains practised in Bengal, Odisha and Jharkhand

Evidence of the sweeping influence European Renaissance had on our cultural resurrection is found in the architects who led the movement. Lawyer, classical artist and activist E. Krishna Iyer, Bharatanatyam dancer Rukmini Devi Arundale, Rabindranath Tagore and art scholar Kapila Vatsyayana were among those who remodelled cultural India for posterity.

The iconic Rukmini Devi, a convent-educated Brahmin whose father was a member of the elite Theosophical Society of India, is near-synonymous with the ‘invention’ of Bharatanatyam. On watching her friend, the renowned Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova, perform Dying Swan, Rukmini Devi was inspired to learn dance, and the call to roots soon touched her, coloured by a strong leaning towards bhakti. That’s the point at which Sadir nac was transformed. Ananya Chatterjea writes about the symbolic “weight” of the nomenclature: “Supposedly it reflects the amalgamation of bhava, raga and tala, bha-ra-ta, at the confluence of which dance is located. However, its simultaneous…claiming of affiliation to Bharata, the author of Natyashastra, suggesting its adherence to the standards of “classicism” outlined in that scripture, as well as to Bharat, one of the indigenous names for India, implying its status as the national dance form of India, are hard to miss.” Under the guidance of her friend (and theosophist) Annie Besant, Rukmini Devi deterged the dances of their toxic association with prostitution, by “shifting the foundational emotion from sringara, the erotic mood, to bhakti, the devotional mood,” Chatterjea writes. This turn was institutionalised through the establishment of Rukmini Devi’s Kalakshetra College of Dance and Music in 1936, where the new, spiritually exalted form of Bharatanatyam, born from the ashes of Sadir, was propagated. A large-scale sanitisation and Sanskritisation of India’s dances were witnessed across the board. A systematic suppression of the physicality that had seeped in from the Mahari repertoire—with the scope of movement of the hips restrained—defined Odissi.

And Sanskritisation? That’s a kind of pseudo-movement in itself, with a similarly purged, spiritual Sanskrit itself deployed to de-eroticise and ‘classicise’ dance. “If you really study the literature and texts, you’ll see a strong influence of Telugu in Bharatanatyam. The padams, javalis, kirtanas are all in Telugu. It shows the art traversed that region too,” says Helen Acharya, secretary of dance, Sangeet Natak Akademi (SNA). In the new order, the literature of the dances in their original, local tongues began to be rewritten in Sanskrit. Chatterjea mentions how the Odissi mudras or hand gestures were also rewritten to a uniform grammar for “movements”.

Odissi heavily borrows from Mahari, which, says sole practitioner Rupashree Mahapatra, “is only for Lord Jagannath”, but has been banished from Odisha’s temples

Photograph by Vivek Tripathi

Many, like Odissi master Guru Debaprasad Das, objected to this brutal codification, but many rode the wave. “The sanitisation happened in every artform,” says Manjari Chaturvedi. “The classic case is of the composition ‘Phool gendwa na maro lagat jobanwa ma chot’, changed to ‘Phool gendwa na maro lagat kalejwa ma chot’. Jobanwa clearly meant breasts, kalejwa was more abstract.… Even Kathak developed as a bhakti-dominated art with stories on Krishna and Radha, which was fair because Krishna is a favourite deity for all performing arts, but the weeding out of amour from dance and music was deliberate.”

A ‘Hindu’ Confection

Chakravorty has talked of how, under an aggressive governmental push for legitimising Brahminical renderings of dance, Kathak started losing its Islamic traits of salami or thata, even farmaayishi. The Muslim headgear, worn well into the 20th century, started to disappear as well.

“The national ideology of a pan-Indian Hindu culture, derived from ancient Sanskrit texts like the Natyashastra, helped textualise Indian dances regardless of their specific regional or religious histories. The Brahminical lineages of Kathak were emphasised by dance historians such as Sunil Kothari….. (He) shows the strong relationship between Kathak and the Raslila tradition of Vraja and Mathura in medieval times but fails to show how they are traced back to Vedic antiquity…a gap of over 2,000 years,” Chakravorty argues in an essay. The Islamic influences were gradually diluted by the overpowering Hindu-Sanskrit dialogue, propagated through the new male custodians who steadily replaced the banished female artistes not just in Kathak, but in Odissi too.

Masculinising dance was a ruse to weed out soft, sensual feminine movements, and thwart condemnation. The takeover of men became a parallel tool for the suppression of female practitioners in the 20th century revival. By the 1930s, Kathak saw the rise of the Maharajs—Shambhu, his brother Acchan, and then the latter’s son Birju, all of whom went on to become household names. More and more elite Brahmin girls were brought under their tutelage—submissive subjects of the male guru. (This while female reformers like Madam Menaka and Sadhana Bose found themselves receding into the background.)

In Odissi, the most widely practised form emerged from the school of Kelucharan Mohapatra, an exponent of the Gotipua style of acrobatic dance. The gotipuas are young, pre-pubescent, cross-dressing boys, whose art is said to have part-martial origins, evolving in the akhadas or gymnasiums set up in the court of King Ramachandradeva of the Bhoi dynasty (circa 17th century). The Vaishnav saint Chaitanya Mahaprabhu too is said to have invited young boys to dance in the procession for Lord Jagannath when menstruating Maharis were barred from performing by temple priests. “At any rate, the typical markers of Mahari, the rounded lines, the overt sensuality, the displaced hip marked by the bengapatti, the heavy silver belt tied around the hip, are overshadowed by the Gotipua insistence on a much more acrobatic, linear style, characterised by jumps and extensions. Several of the current gurus of Odissi, largely responsible for its reconstruction, were trained in this style,” Chatterjea writes. Post-independence, the SNA, formed in 1952, pushed for reviving the gurukul system; again a picture that placed men at the top and in the centre.

Folk vs Classical

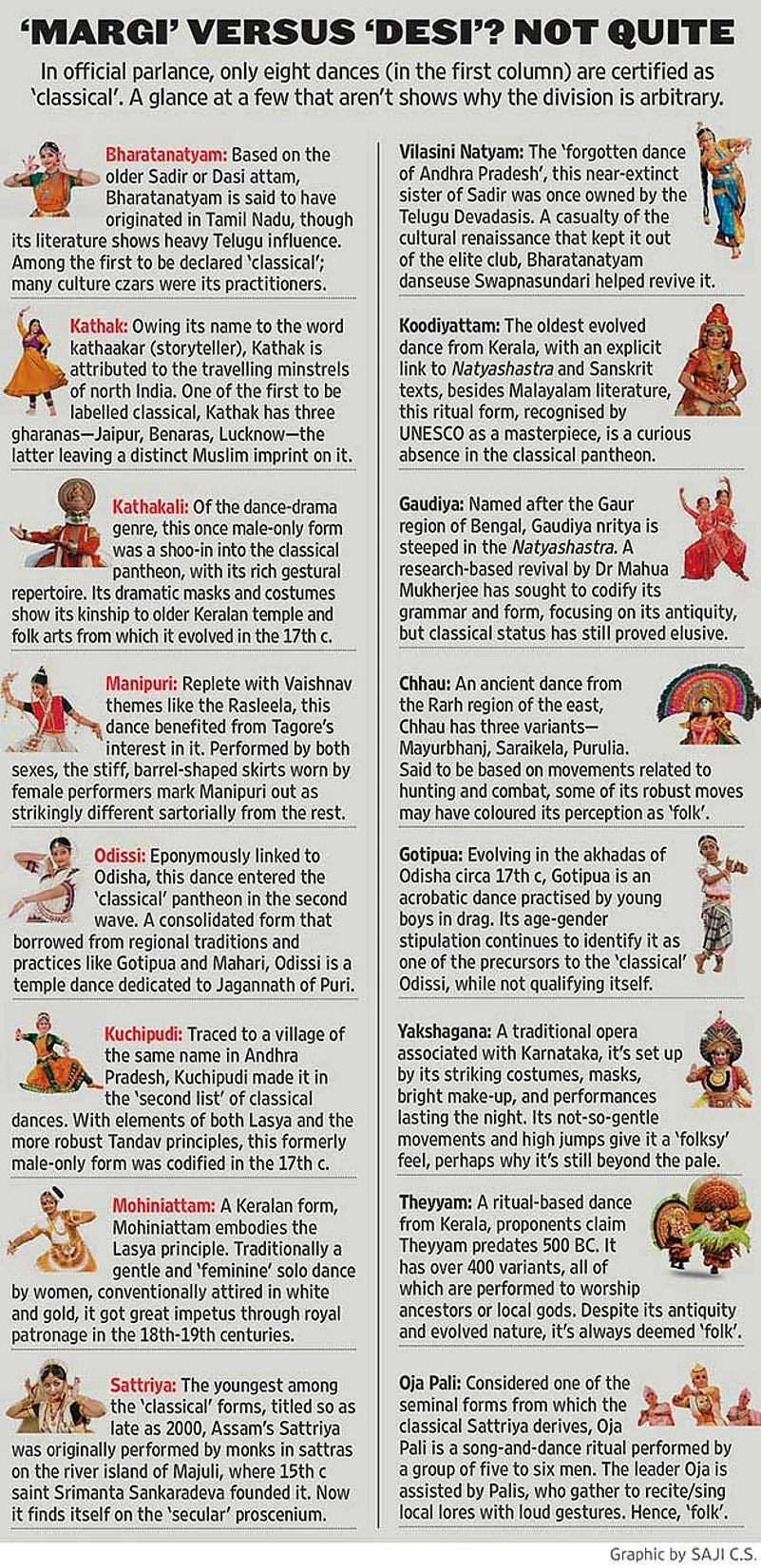

The old forms, powerful and sensual, now lay like debris at the nation’s construction site. It wasn’t exactly a conspiracy, but a collective zeitgeist. “They did what they thought to be right at the time. We should do what we think is right for our time, without dragging them down,” says Padma Shri Leela Samson, a disciple of Rukmini Devi, who has headed Kalakshetra and SNA. “Whatever styles can be revived should be revived.” One strand in the story, however, is also about how we define things. The inherent many-ness of the Indian gene can scarely be made to fit into boxes, but one order of classification has been as pervasive as it is arbitrary: the divisions of art-forms into ‘folk’ and ‘classical’, or desi and margi. The new form of Bharatanatyam showed the way, and the SNA conferred ‘classical’ status on it, as also on Kathakali, Manipuri and Kathak first, followed by Odissi, Kuchipudi and Mohiniattam. Assam’s Sattriya joined the pantheon as late as the year 2000.

Bharatanatyam was an unsurprising choice in the ‘first list’. Kathakali, Kathak and Manipuri too were upheld by influential individuals. Kathak boasted of names like Jaddanbai (Nargis’s mother) and Gauhar Jaan, close associates of the Indian National Congress. Manipuri received extensive visibility thanks to Tagore, who incorporated it into some of his Rabindra Nritya choreographies. It was renowned Malayalam poet Vallathol Narayan Menon who evangelised on behalf of Kathakali; using all his resources and social authority, he was instrumental in convincing young men in Kerala to not leave the art-form marooned. His connections with Rukmini Devi and Uday Shankar helped Kathakali go global too at a very early stage. And Sattriya’s entry coincided curiously with Assamese singer-songwriter Bhupen Hazarika’s tenure as SNA chairperson.

“It’s always a conscious decision to make a dance ‘classical’,” says Sudha Gopalakrishnan, Koodiyattam scholar and executive director of Sahapedia, an online resource on Indian arts. The so-titled eight ‘classical’ dances were offered as forms grounded in the Natyashastra, a comprehensive treatise on the performing arts dated to the 2nd-5th c AD. Desi/margi is a slippery classification, and “caused problematic erasures”, according to Chatterjea. Margi, referring more to a specific marg or aesthetic ‘pathway of development’, was “inaccurately translated as classical”, she writes. And desi was literally interpreted as ‘folk’. An artificial class hierarchy thus came to be instituted, because it’s not always very self-evident why one form deserves to be in or out.

Kerala’s Theyyam is embedded in ritual, faith, community

“We’ve been trying to get classical status for years . Every time we meet Akademi authorities, they tell us they consider everyone to be classical, but that’s not true! Gaudiya Nritya follows the Natyashastra to the core and yet we are in the waiting line,” says Banani Chakraborty, a practitioner of Bengal’s native form. The classical tag naturally brings increased state patronage, hefty scholarships, research grants, larger platforms. “We barely find representation in official bodies or festivals. At the recent Uday Shankar Festival in Calcutta, Gaudiya received merely two slots despite being the state’s own art,” says Chakraborty.

While a dance’s level of sophistication in terms of grammar is upheld as the litmus test for ‘classicity’, forms like Gaudiya and even Koodiyattam, with its part-Sanskrit literature, are stuck in a limbo despite checking off all the boxes. “Norms apply to all, so-called classical or folk. Those who refer to our art-forms as classical perhaps do so because they believe they are codified in ancient Sanskrit and regional texts, in sculptural evidence and in cultural memory. It’s time to question nomenclatures based on specific periods of European history. They do not refer to us,” Leela Samson says. However, the definitions have already coloured our perceptions, and in ways not reflective of the complex continuum that marks the arts.

“The ‘classical’ is dependent on the folk, and folk also draws a lot of energy from classical,” says Gopalakrishnan, citing the example of Kerala’s Theyyam. It can’t be considered as “just a performance”, she says. “There’s ritual and belief involved…an involvement of the community.” With Sattriya, she says, performances suddenly became ‘solo’, and got modified. “Changes are made to the text. The entire aesthetic changes when there’s a conscious decision to turn a dance ‘classical’,” says the scholar, who believes codifying exclusively by the Natyashastra is detrimental to the health of our dances. “Koodiyattam is unique as it draws from Malayalam and Sanskrit literature, local traditions, everything. Why should our dances have to follow only one text in order to be recognised as classical?”

The arbitrariness leaves no room for negotiation even for forms that apparently satisfy all criteria for classicity. “Chhau is a 20,000-year-old dance that was practised by the soldiers of the Rarh region. It’s perhaps older than any known Indian classical dance, is highly evolved and codified, with three distinct strains practised in Bengal’s Purulia, Odisha’s Mayurbhanj and Jharkhand’s Saraikela. If Chhau doesn’t qualify as classical, I don’t know what does,” rues Chhau scholar Sharmila Banerjee. Such are the elusive prescriptions left behind by the architects of our cultural republic.

(With Usha Ramesh in Tanjore)