Before entropy, when the entire physical universe dissolved into chaos, reading and writing came early to many like me. This was not the prodigy syndrome—the kid quotes poetry or plays piano when his potty habits aren’t socialised yet—but something akin to osmosis, where your surroundings seep in through the body’s membranes.

This was, in hindsight, inevitable. As a Bengali, or Bong, as we are affectionately referred to, we were expected to eat rice, potato cooked with opium seeds called aloo poshto, devour fish and books and write poetry. For most, the last would stop with the onset of increasingly demanding examinations, or in rarer cases, with a realisation of the awfulness of our output. Reading was destiny, bundled with homoeopathic remedies for indigestion.

Nearly half a century ago, a non-Bong friend of my father saw me flipping pages with my left hand while effortlessly tackling fish bones and rice with the right. “This way you’ll lose both pleasures, of a good read and a good meal,” he quipped. I heeded his sage advice for as long as he was around the table.

Like many Bongs, my home was full of books and publications, not particularly well organised, despite my mother’s heroic efforts to impose order. They included Soviet glossies, publications like Imprint, sponsored by the CIA during the Cold War, as well as ‘little magazines’ like Anushtup, Krittibas and Baromash, which published the finest Bangla writing for, maybe, three generations.

The annual Calcutta Book Fair was a great magnet for people all over India, as well as neighbouring countries, a mammoth version of today’s fancy LitFests. One of its main attractions are the tiny stalls put up by high quality, but relatively unknown, publishers—Subarnarekha, with one outlet in Santiniketan and another in an obscure alley off College Street called Patuatola Lane—was a personal favourite.

The outstanding feature of Subarnarekha’s edition of Hutom Pechar Naksha, probably the greatest satire of 19th century Bengali life, by Kaliprosanna Singha, better known as the translator of the Mahabharata into Bangla, was its brilliant annotations by raconteur and scholar Arun Nag.

Another classic it revived is perhaps the oldest cooking manual in India, Pakrajeshwar. It was first published around 1831, and priced at one rupee. It compiles recipes dating back to Vikramaditya and the court of Shah Jahan. Subarnarekha made its edition accessible to contemporary readers with an introduction and glossary explaining antiquated terms.

In Calcutta, most people I visited—my parents’ friends and their children—just read whatever and whenever they could. Our diet included much of Bengal’s rich literature for children: Rajshekhar Bose’s translations of the epics, Abanindranath Tagore’s often phantasmagorical writing, Satyajit Ray’s incomparable Feluda mysteries and Professor Shonku sci-fi and Saradindu Bandopadhyay’s tales of sleuth Byomkesh Bakshi. Somehow I developed a lifetime addiction to absurd literature, driven by Satyajit’s father Sukumar’s writing and those of Rajshekhar Basu’s doppelganger, Parashuram.

My parents were friends of the historian and polymath Susobhan Sarkar, whose home and garden, in Calcutta’s Naktala, was host to legions of former students, colleagues and fellow travellers like J.B.S. Haldane, the great British geneticist who took up Indian citizenship because of his Marxist beliefs. Too young to comprehend anything being discussed, I was left blissfully alone to browse through Sarkar’s immense library.

There, casually interspersed with the Braudels, Gramscis and Rudes, was his substantial collection of crime fiction: I devoured all of Conan Doyle there, as well as Agatha Christie, Perry Mason and Raymond Chandler.

There too, I made acquaintance with the pioneers of ‘regional’ crime fiction: the Swedish Marxist couple Maj Sjowall and Per Wahloo, H.R.F. Keating, creator of the delightful Inspector Ghote of the Bombay Police, as well as Judge Dee, who apparently lived in 7th century China and whose exploits were fictionalised by Dutch Sinologist Robert Van Gulik.

Thereafter, as our pubic hair grew in tandem with a belief in our own smartness, we spouted the verse of post-Rabindranath ‘modernist’ poets. In hindsight, many of them were incomprehensible or execrable, but Eliot, Auden, Larkin, Shankhyo Ghosh and Shakti Chattopadhyay are still favourites.

We also discovered European and Latin American writers. One day, walking through the portico of Presidency College, I was mystified to see handwritten posters calling for “the immediate release of Comrade Guzman...or else”. Enquiries from greater revolutionaries revealed that the aforesaid comrade was leading the Shining Path to liberate Peru. Ah, in those innocent days before live television and internet, what did we know of Peru, Sendero Luminoso or the great Comrade Guzman?

Nevertheless, revolution was in the air, though our moustaches were no match for Castro’s or Che’s luxuriant growths. Neruda, Albee, Pirandello, Lorca, Marquez all spoke to us, leaving us little wiser, but feeling superior to others on the same S-15 bus-ride.

Around this time, we began smoking some more interesting stuff than tobacco, committing ourselves forever to the legacy of Henry Louis Derozio of Young Bengal. We found worthy companions—in Aldous Huxley, Allen Ginsburg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Jack Kerouac, Shakti Chattopadhyay (again), The Tao of Physics, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance...you get it, the 1970s lust for a decade gone by.

So much of what we read was haphazard, driven by chance, coincidence, name-dropping or fortuitous meetings with people who became friends for life. Those who read avidly—there were plenty of folks like that before the age of cable TV, Google and YouTube—spent hours, months, years happily prowling seedier areas of cities where departing hippies would leave their intellectual flotsam behind.

There, between piles of tattered Lonely Planets, you could chance on random volumes of Frank Herbert’s Dune saga (not necessarily in the proper sequence, but how did that matter, then?), or a tattered copy of Penguin Modern Poets with just ‘Yevtushenko’ written on the cover. You could ask an ancient Anglo-Indian who hoarded vinyl records to tape copies of The Moody Blues, or Queen, or whatever. Or buy back issues of Punch, the New Yorker or Rolling Stone to cart back home if you had a few extra rupees.

Believe me, these hours of prowling these chaotic intellectual jungles were no less rewarding than, well, when Columbus washed up on the coasts of the New World, or Al-Biruni stumbled into India.

Then came the internet and everything seemed to change forever. Or did it?

For one, it decimated the ecosystem of the used-book stores. College Street, the epicentre of this trade in Calcutta, is now choked with crammers for aspiring ‘Bank PO’ or ‘IIT-JEE’ or ‘Medical Entrance’ grads.

Just off tony Park Street is fast-gentrifying Free School Street, originally named after an Armenian school located there. It is now named after Mirza Ghalib, who never lived there, and not after William Makepeace Thackeray, who was born there. Due to its cosmopolitan population of backpackers, the used-book stores here still fare better than College Street.

But if you’re looking for well-thumbed copies of George Simenon’s Inspector Maigret series or hand-me-down volumes of Philip K. Dick’s paranoid sci-fi, forget it. Chetan Bhagat, Stieg Larsson or Chicken Soup For Someone-or-Other’s Soul will hit you before you get a chance to ask Who Moved My Chandler? And yes, the upmarket Fodor’s now competes with Lonely Planet: despite the Great Recession, today’s backpackers must be better off than their parents.

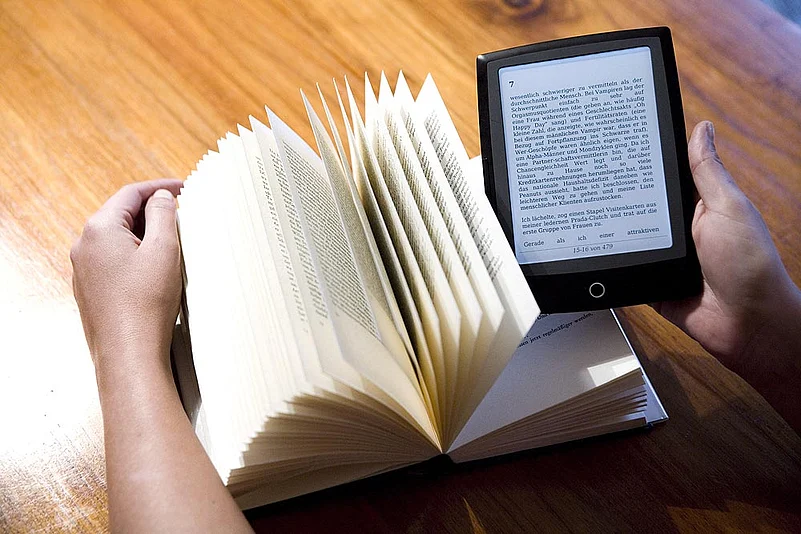

Hence, my Kindle Paperwhite: it’s around six inches diagonally across, weighs 205 gm, about the same as a slim paperback and at any time I carry around 250-odd books on it. With its cover on, you can hold it in your palm exactly as you would hold a book open.

If you keep it on airplane mode, it works seven weeks or more on a single charge. Above all, it minimises discord by glowing in the dark: now finally I can read in bed while my spouse sleeps. Kindle has competitors like Kobo, which must be as good as it is, perhaps better.

Of course, digital reading has drawbacks. It’s impossible to replicate the beauty or texture of holding a physical copy of a graphic novel like Art Spiegelman’s Maus or Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns in any online format.

Much of digital publishing is still short on serious work in social science and humanities—though science, math and engineering do well. And the virtual shelves are almost bare of non-Anglo Saxon, non-European vernaculars. Though, I say this only from my Bangla browsing experience.

But, with e-readers, I have rediscovered some of the joys of serendipitous discovery—through poking around ill-lit digital back alleys of online publishing and peer-to-peer sharing. I say without blushing that I downloaded Simenon’s entire Maigret corpus—a top publisher is reissuing them at a painfully slow and overpriced rate—for free, courtesy generous online peers.

I still have my piles of John le Carre and Elmore Leonard hard copies, but I don’t have to rummage through them in a room at the rear of our apartment, where they reside, after I found everything they ever wrote online.

In a 1939 essay called The Total Library, the great Jorge Luis Borges imagined a library of astronomical size, the sum total of all human knowledge, imagination and wisdom. He warned that it would also be a “subaltern horror”, whose “wildernesses of books run the incessant risk of changing into others that affirm, deny and confuse everything like a delirious god”.

Later in life, Borges said, “I have always imagined that Paradise will be a kind of library”. I share this dream, in all its print, paperback, hardbound and digital

manifestations.

(Parashuram Ray is a senior journalist)