Samidha Khandare made news just a few months ago when she received her medical degree as she herself lay on a hospital bed. She’d been undergoing treatment for tuberculosis. Tragically, she hit the headlines once again: on June 30, she died of multiple drug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB). A nursing student too died of TB at the Nair Hospital. Since then, at least two other staff members at the hospital have contracted the disease. Across the state, at least 26 doctors—either residents or those interning in the fifth year of the MBBS course—have contracted TB in the last year.

It’s alarming that those who provide healthcare end up suffering from the diseases they treat in patients, and speaks of lack of hygiene in hospitals and bad living conditions. Treatment of TB, depending on whether it’s primary or drug-resistant, can take 3-24 months. MDR-TB, which has become a cause of concern in Mumbai, can worsen to extremely drug-resistant TB, which is almost impossible to cure. And those are just the bare facts. A look at the daily lives of these doctors provides some clues.

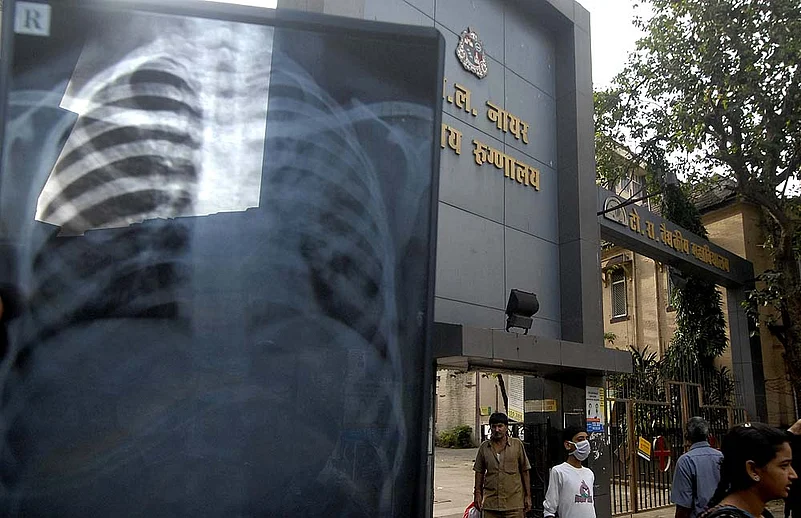

At Nair Hospital, like at any municipal- or government-run hospital, the stench of disinfectant hangs in the air. The halls and corridors are crowded with patients and their relatives, walking in, walking out, waiting at counters, or huddled in small groups, silent or noisy. Anyone who can help it will not stay. On the eighth floor of the same building are the rooms for women residents. In one room, three or four young women, who have just finished a long shift, are fast asleep. The doors are left open, because they are too tired to get up and open it for others. Clothes spill out of suitcases. Hot plates and some utensils for making tea lie about. The walls are damp, windowless. It’s more or less the same story in all public hospitals: everywhere the residents’ hostels are overcrowded, and a room for two is often shared by three or four.

Samidha, who died after battling TB for six months, used to live in one such room. “Becoming a doctor was a dream she worked towards from childhood,” says her brother Dr Shekhar Khandare. “We come from a modest background. My father is a school teacher. There were so many hopes and aspirations—all cut short even before it could begin. She contracted TB at the hospital.”

Niranjana (name changed) was infected when she was in the third year of the MBBS course at the Sion Hospital. During the infectious period—when the disease can spread to others—she had to go home for more than a month. Since she comes from a hinterland town, that meant little contact with classmates. “Everything is affected—studies, work and normal life. I just want to complete the course and get out of Mumbai. I am fed up,” she says. She’s now waiting to complete her internship at a municipal hospital. For years, doctors at the Sion Hospital, Nair Hospital, KEM Hospital, the JJ Hospital and the Group TB hospital—all run either by the city administration or the state government—have been complaining about poor living conditions and long working hours. Also about how lack of hygiene is putting them at extreme risk.

Too many A cramped residents’ dorm

TB is not only life-threatening, it drains the family of resources during the infuriatingly long treatment period. Drug-resistant TB is hard to diagnose; it may take as long as two to three months, and requires a culture test. Last year, 36,417 cases of TB were reported from municipal and government dispensaries and hospitals. The death toll from the disease was 6,921, according to a report by Praja, an NGO working on civic issues. One in five persons who contracts TB succumbs to it. And these are just official records. The numbers could be higher, for many poor patients drop out of treatment. Undiagnosed, untreated patients only increase the risk of spreading infection, in hospitals and outside. There’s also the social stigma—a hangover from the 1960-70s, when it was the poor or people from the labour class who contracted TB the most. It persists even though many people from the middle and upper middle classes are contracting the disease now.

“There are three reasons for doctors getting TB—unhygienic living conditions, lack of nutritious diet, no time for breakfast or dinner due to long working hours. Naturally, it lowers immunity, which is a major factor,” says Dr Santosh Wakchaure, president of the Maharashtra Association of Resident Doctors.

The view is echoed by numerous doctors. “During the rains the rooms are not just damp, but some rooms have streams of water coming in. We are so tired, we don’t bother. We come from different parts of the state and can’t go home even if we are sick. We don’t even have a separate canteen and have to eat with the patients. The risk of infection just goes up with every little thing,” says a postgraduate medical student at Nair Hospital who didn’t want to be named.

Health minister Suresh Shetty admits that the workload by number of patients has tripled for the outpatient departments and doubled for the in-patient departments. “In the urban areas of Maharashtra, the problem aggravates because we get patients from the neighbouring states of Gujarat, Karnataka and Madhya Pradesh too.”

Now, after the death of three doctors from TB, efforts at improvement are being made. The bmc is starting a high-protein breakfast programme for doctors at Sion Hospital. “Our survey shows that 50 per cent of our doctors do not eat breakfast. Some 500 residents will benefit from the programme,” says additional municipal commissioner, Manisha Mhaiskar. However, no one really knows if the residents will find time and energy to consume that breakfast and build their immunity. That issue comes under department of medical education, which administers their training and duty rosters. Vijaykumar Gavit, the minister for medical education, remained unavailable for comment despite repeated attempts. And doctors remain suspicious of the efforts, patiently waiting it out to finish their courses and move on to healthier places. Surely, they would prefer the work conditions private hospitals offer to government service.

By Prachi Pinglay-Plumber in Mumbai