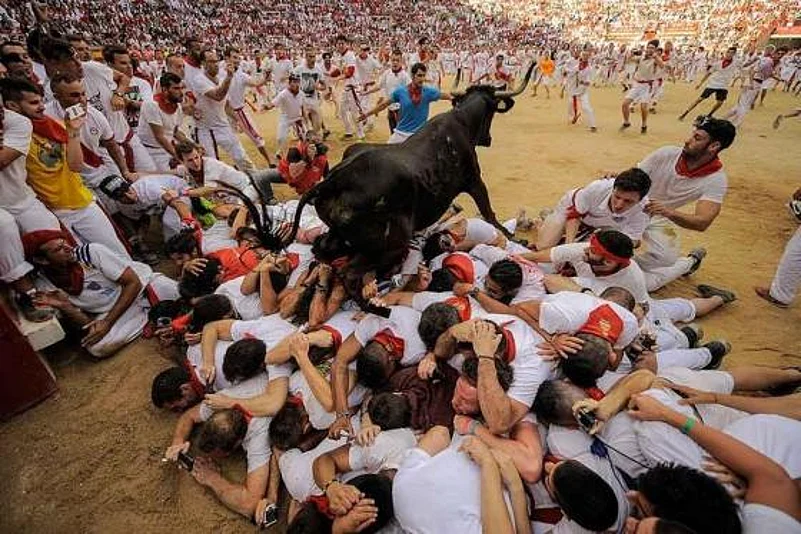

The battle over Jallikattu, the now infamous bullock sport, is far from over. New battle lines have been drawn -- with a group of youngsters backed by the state government locking horns with animal rights activists to defend their tradition.

Whichever side wins, the places that will be, and have been, most affected are the villages and small towns of Tamil Nadu. When jallikattu is viewed only through the prism of cruelty against animals’, aspects of local economy that not only nurture indigenous breeds but survive on it get ignored.

It will take years to clearly understand the repercussions of the decline of the traditional cattle economy. What has not been assessed yet is the impact of ban on the future of native species (and its numbers) and the rural economy dependent on it.

Two years after the Supreme Court had ruled that ‘bulls cannot be allowed as performing animals, either for Jallikattu events or bullock-cart races in the country’, there was a fresh move to amend Section 22 of the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act 1960 (PCA) for getting the racing bulls back on the village racing tracks. Cleared by the Ministry of Law and Justice, the proposed amendment sought to ‘continue performance of trained animals under the customs or as a part of the culture, in any part of the country’.

The proposed amendment is yet to get the Parliament’s nod, a group of organisations under the aegis of the Biodiversity Conservation Council of India (BCCI) have invoked Articles 8(j) and 10(c) of the Convention of Biological Diversity (CBD), to which India is a signatory, which seek to ‘respect, preserve and maintain knowledge, innovations and practices of indigenous and local communities’ as well as encourage ‘customary use of biological resources which are compatible with conservation and sustainable use requirements’ in support of the government’s move.

‘If these cultural events remain banned, livestock keepers will be forced to abandon the raising of native livestock, which are already threatened on account of farm mechanization,’ argues Karthikeya Sivasenapathy, who in addition to BCCI managing trustee is also on the management board of the Tamil Nadu Agriculture University.

Contesting the sweeping claims by the Animal Board of India (AWBI) that the animals are tortured during the event, the activists wonder why would the owners harm their own bulls, which is like a ‘family member'.

Prevalent across Maharashtra, Karnataka, Punjab, Haryana, Kerala and Gujarat, this sport has been in vogue since the days of the Indus Civilization. What is considered cruel by animal rights activists today has instead been symbolic of the intimate bond between the cattle and the peasants since time immemorial. Ancient Tamil literature (Sangam, 2nd Century BC) refers to it as Eru Thazhuvuthal, meaning hugging the bull. Known by diverse nomenclature, there are many variants of this sport across the country.

While Jallikuttu in Tamilnadu involves holding on to the hump of the bull and running along as long as one can hold onto the animal, in coastal Karnataka the race called Kambala involves testing athlete’s endurance of running with a pair of he-buffaloes on a slush racing avenue. These studs are trained, fed and nourished through the year for the annual racing event, which is a matter of pride for the owner and the village.

Since these bulls are genetically superior to other animals, these are used for mating to improve the quality of herd in the village, and beyond.

Ever since the Supreme Court had banned Jallikattu and similar racing events in May 2014, there have been reports regarding distress sales of quality bulls from many parts of Tamil Nadu. Farmers sold their bulls for a pittance, and several of these found their way to the slaughterhouses.

Since evolution of quality breeds is a product of complex interplay of nature and culture, cultural events hold special significance in preserving native species. In fact, Kambala is observed as a thanks-giving to gods for protecting the animals from disease.

While animal rights are a matter of serious concern, so is the need to preserve native species which stand threatened due to overt machination of agriculture. There is hardly any incentive for livestock keepers to maintain quality herd. In many parts of the country, such bulls are found abandoned, and are a threat to civic life on the streets. If the sport is banned, it would bring curtains on many native breeds. The future of the Kangayam breed, which is preferred during Jallikuttu, one of the five existing pure breeds of the state is in dire straits.

These events are races and not bull-fights of Spain. However, there is no denying the fact that safety of the animals should be paramount in such sporting events. There should be rules to conduct these events such that there is no violation of animals’ safety. While rules for the conduct of the racing events should be made stringent, erasing the intangible cultural heritage from the map of the country has costly ramifications.

Dr Sudhirendar Sharma is Director, The Eco-logical Foundation, New Delhi.