The balmy part first. Two-and-a-half years ago, the country was gifted a separate ministry dedicated to further develop and popularise ayurveda along with a few other indigenous medicinal systems. Thus came Ayush in November 2014 after the present government upgraded a department by the same name. This fiscal, that ministry’s budgetary allocation was raised by 8 per cent—to Rs 1,428.65 crore.

Now the flip side. For all the apparent boost, the new ministry’s media machines have failed to evoke sufficient public awareness and confidence in ayurvedic treatment to get people to use the services of its clinics in cities and villages. Notwithstanding its millennia-old history of healing, this ‘way of life’ remains the second or last alternative to allopathic treatment for most Indians. Why has the system that uses natural resources failed to satisfy even those who would rather not opt for allopathic treatment?

To a large extent, the blame goes to a lack of focused administrative attention and non-existence of an enabling policy environment and the absence of scientific standardisation of the medicines. Health being a state subject, the Centre only makes overarching guidelines. It is for the states to implement them. The Drug and Cosmetics Act has a provision for ayurvedic medicine. But the herbal drugs and bhasmas produced under the science are specific to different states. This often results in drugs without proof of efficacy. “We have no fixed standard for trial of ayurvedic drugs,” says an ex-official of the ministry. “Drug firms may show trial data on just a handful of patients and are still eligible to get a licence for mass production.”

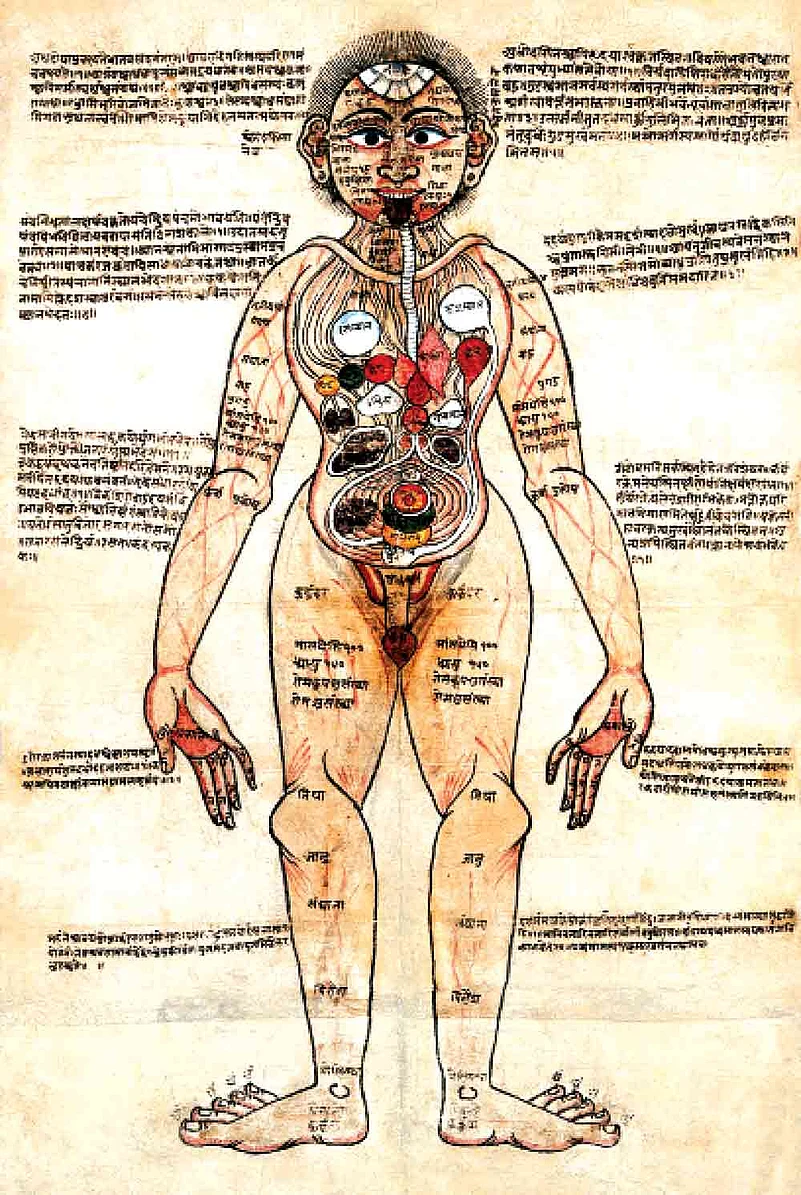

An 18th-century Nepalese ayurvedic drawing on human body anatomy

This, when the Indian ayurvedic drug market is estimated to be growing at a compound rate of 16 per cent every year. Yet, there is almost no regulation on advertising of ayurvedic products. Result: consumers are often duped into believing exaggerated claims of cure. A recent example is BGR-34, a blood-glucose regulator, jointly developed by CSIR-NBRI and CSIR-CIMAP. The drug went into mass production and has been a runaway hit. A lawyer, Manu Govind, has challenged the manufacturers in the Kerala High Court, alleging the claims weren’t backed by technical or clinical data.

Dr Anand Srinivasan, chairman of the Delhi-based Maharishi Ayurveda Hospital, says most manufacturing units for such drugs are substandard. “India has more than three lakh manufacturing plants for ayurvedic drugs. Only 20-30 of them produce drugs that might meet required standards,” he says. “Most others are one-room set-ups.”

This is one of the major reasons that leave patients ineligible for insurance cover when it comes to ayurvedic treatments—even from reputed hospitals. “No standards for cost of procedure is available,” says a medical insurer. “Most of such treatments can easily fall under ‘experimental’ category.”

Since herbs are their components, ayurveda drugs have been deprived of recognition from the US Food and Drug Authority or other international bodies. This, however, can be “easily rectified” by changing the guidelines for drug trials, according to the former Ayush official. “We need to develop a format of standardisation that follows the rules of ayurveda instead of that of allopathy. By using traditional knowledge and presenting it in international forums, we can seek accreditation for mass distribution of such drugs in a more organised manner.”

The onus for research and development of new ayurvedic drugs, too, lies almost solely in the hands of the government. The Central Council for Research in Ayurvedic Sciences (CCRAS) under Ayush is responsible for the development of drugs and creating a nuanced understanding of ayurveda principles. Dr Neera Vyas, deputy D-G of the 1978-formed CCRAS, rues laxity in promoting research since the new ministry was formed by upgrading a 1995-constituted Department of Indian Systems of Medicine and Homeopathy, which was renamed Ayush in 2003. “There still don’t exist guidelines for the testing and development of drugs under the ministry,” she says.

Another CCRAS official says most trials undertaken in the organisation do not last more than three months, and often do not conclude anything new or ground-breaking. “Our research into ayurveda is not improving upon the existing principles in texts,” he states. “Several western countries are doing better work in understanding the basics.”

Three years ago, the Narendra Modi administration floated a mission to create a data-bank of information on ayurvedic treatments and compositions of medicines, many of which are now lost or not available in full. The country has 350 ayurveda colleges recognised by the Central Council for Indian Medicine (CCIM). Most students opt to study ayurveda only as a second option—after MBBS. On completion of the ayurveda degree, many graduates practise allopathic medicine—something allowed in states like Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Punjab and Himachal Pradesh. Some study further and become nurses in hospitals.

The total number of seats available for bachelors in ayurveda in the country stands at around 17,000—a number growing every year, as more colleges are accredited. Yet, admission trends suggest that about one-sixth of these seats remain vacant. The syllabus excludes practical knowledge; there’s no mention of the ways of making the herbal potions. What’s more, the courses have an overarching influence of allopathy.

Points out Kerala-based Dr M.S. Valiathan, a renowned cardiologist who took to ayurveda recently: “Mixing our traditional teaching with allopathy only sullies the sciences, giving students half-baked knowledge about ayurveda.” Ravi P.V. is pursuing a course in an ‘alternative medicine’ in Tamil Nadu, having failed to get through to a medical college. Does this ayurveda student in Coimbatore wish to set up his own practice subsequently? Ravi shrugs and says, “I think I’ll do a small course in nursing after this so that I can get a job in a hospital.”

Vineetha Muralikumar, president of the CCIM which is the ayurvedic counterpart of the Medical Council of India and is responsible for vetting colleges as well as registration of ayurvedic doctors in the country, says a mix of traditional medicine and allopathy has become “important”. “The government needs to ensure that the ayurvedic practitioners have at least basic knowledge of allopathy.” According to her, low availability of doctors in rural Maharashtra and UP is leading many ayurveda practitioners to treat patients with allopathic medicines.

Vinod Kumar, an ayurvedic doctor from Kerala, says the syllabus in ayurveda colleges is stale. “It deprives students of knowledge about new discoveries. There must be constant updating,” he says.

Ayurveda laureate Padmaja Ramachandran, also from the same southern state, regrets a decline in the number of books taught in ayurveda courses. “When I was a student a few decades ago, we had to learn every shloka in the Ashtanga Hridayam, which is the most crucial text for ayurveda. We also had supplementary reading material, which is not present anymore,” she says. The result: an inevitable decline in the quality of present-generation doctors from colleges.

The Ayush ministry rules prescribe that INStitutes comply with certain requirements, be it with the teaching staff or with beds in the attached hospital and its patient inflow. The biggest problem, to some, is a dearth of quality teachers. “Over the past few years, duplication of teachers has been a major issue,” says Dr Vineetha. “Several teachers have registered themselves in different states, showing an exaggerated number of staff available in states as well as colleges.” This means that many of the colleges are fudging the strength of its teaching faculty to get accreditation. Efforts are on to rectify the situation by issuing identity numbers to teachers, says Dr Vineetha. But the process is long drawn.

Sadly, the national health programme policy released by the government does not mention ayurveda. The Trauma Centre under Delhi’s All India Institute of Medical Sciences, taking a leaf from global counterparts, has now joined hands with the Defence and Research Development Organisation to test the efficacy of herbal products in treating wounds. A small but significant step.