When we use a camera, we’re essentially saying: “My own eye is insufficient”. Photographs throw up details neither I nor the mirror can capture. And video offers a way to capture my most evanescent effects, the fine effects I live, that place of intimacy we hanker after—all that which is otherwise lost. The video also captures how much I feel in sexual intimacy. It’s too much for me to imagine how to begin observing it, to try to know myself. With a video camera, I create an observer. The self-conscious part of me retreats into that camera.

Read Also: Selfie Sex On The WiFi

Older generations didn’t have video cameras, nor selfies. Intimacy meant a lot, but something about it was unspeakable, so most of us stopped ourselves from knowing more about those moments. As a civilisation, we only heard about the orgasm as something almost close to and profoundly akin to moksha. You fuse with the other, the other fuses with you—the Devi, the Mother, eternal recurrence, all that. Yet, it was also chimerical: you didn’t know whether you could always reach it. But there is now a possibility of observing myself and returning to that observation, to catch minutiae of myself, which may provoke in me more amorous imaginations, or make me laugh at myself.

My son tells me not to make a big deal of couples recording intimate moments: that it’s technology. It becomes a big deal only when risk looms. Today, perhaps ‘commitment’ is given a far more rigorous trial. Recordings sow a seed of anxiety in the other, especially in a woman. It’s as if I’m saying, while I record myself, that there are two ‘perverted’ beings in this moment. (By perversion, I mean when the intensity of emotion, affect or desire overtakes my capacity to make meaning out of it.) Later I can say, ‘We lived so much! How can you think of going to someone else?’

In catching my perversion such that I can keep returning to it, I make sense of it. Yes, I may still be unable to make sense of it. Somebody can watch a video and wonder what was s/he doing with that person? Also, just as I say I don’t like the look of you and me when we go to a party as a couple, this is a new arena to say we don’t ‘like the look’.

In sexuality, we are competing with the gods. We say it should be perfect—I should be parent, lover, whoever the other wants me to be. A conservative part within me, in a good way, also says you and I are going to enter an exclusive intimacy that nothing should puncture. There is, around the edges, an awareness of the exclusive part, the conservative part. If you become an observer, it’s as if the conservative part says: this is too modern a thing to do.

Now, Khajuraho has paled. Its erotic part has receded. Older people may still be drawn to images closer to the way our gods and goddesses are sculpted, the voluptuousness of those figures, their scale. But to the younger generation what appeals are script, sounds, the way we have arranged our intimacy, the dynamic quality of both partners projecting themselves in ways most people can only imagine. The videos give us a vicarious sense, even if pornography might spoil the pleasure which intimacy preserves. In true intimacy, we are not interested in parts; we are interested in enhancing those parts. Yet, to be almost disabled with the idea of not knowing myself in many parts is also something: There’s a gap in our knowledge about how body parts look in excitement, what they do, the actions they provoke. This is a disability, not knowing how we sound, appear and become almost unified and UNI-focused in what we want.

Intimate sex takes you from ‘I want to know my partner’ to ‘I know my partner’. How do we get there? It’s very enigmatic. I came across a couple who said that after lovemaking they grow into sleep—and the quality of sleep I am told is epochal. Then they wake up together as if from a miracle. Their rhythms were joined together, accentuating the phrase ‘to sleep with’ to mean actual sleep and waking. This too needs to be thought of: there is no camera here but an internal camera, which is recording our coming together.

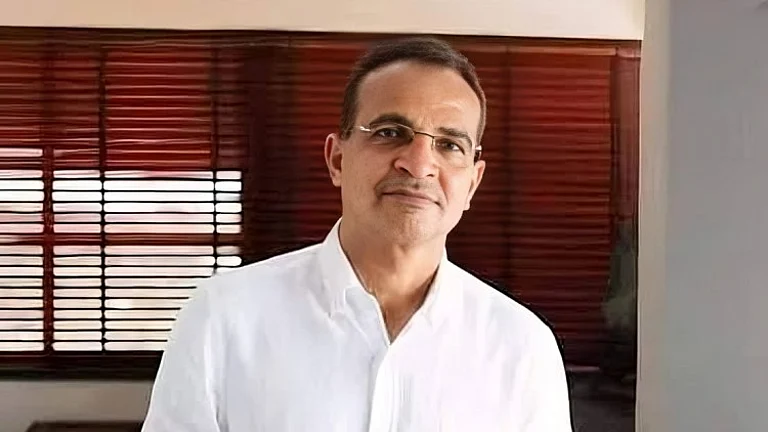

(Ashok Nagpal is a professor of psychology at Ambedkar University)