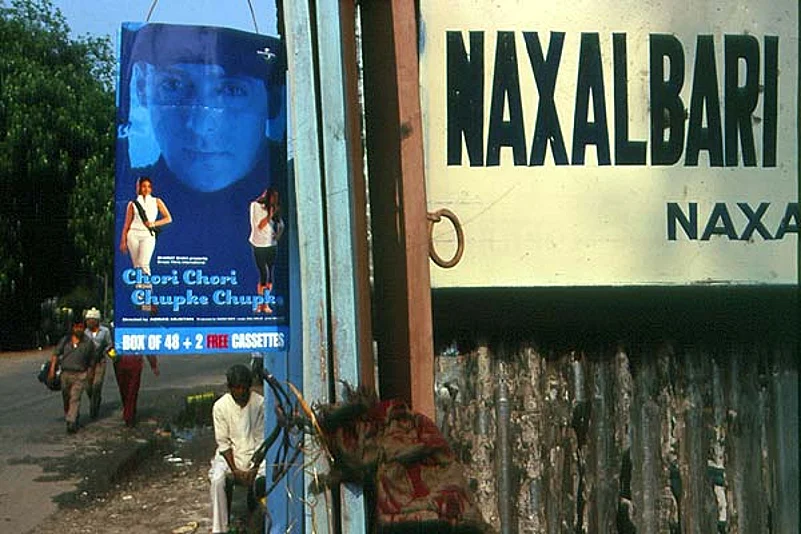

When night falls, they put a lantern on the ground between Kanu Sanyal and me. There's no electricity in Sebdella village, just off the town of Naxalbari near the West Bengal-Nepal border. The one tubewell is also almost dry. Within a few days, the people will have to start drinking from the dirty stream nearby.

This is where it happened: the peasant revolt that, in 1967, gave the world a term—Naxalite—which still evokes hope, rage, grief and fear. Sanyal was one of the key early leaders of that attempted armed revolution, perhaps next to only Charu Majumdar (CM). We are sitting in the courtyard of the late Jangal Santhal, another legendary figure of that movement. It's getting cold. Naxalbari lies on the cusp of the mountains and the plains, a place where you always know you are close to the hills but you never see any. "The Naxalbari peasants' uprising was a true armed mass struggle," says Sanyal. "But after that, the whole so-called Naxalite movement took a terroristic path, a complete deviation from what we stood for here. CM's line was wrong. It was like we were building a small earthen hut, and we just kicked it back to dust again." But dreams live on. They may be different from the ones in 1967, they may even be wild fantasies, but they live. Is there something in the soil here, something in the water of the river Teesta that breeds these visions of freedom, and a willingness to lay down your life for it?

Busts of Lenin, Stalin and a rebuilt one of Charu Majumdar near Prasadjote, where 11 people died in police firing.

CM and Sanyal were with the CPI(M) when they began working with peasants and tea garden workers of the region. On March 18, 1967, the local Peasants' Council announced that it was ready for armed revolt to redistribute all land controlled by the landlords or jotedars, and end centuries of barbarous exploitation. On May 23, sharecropper Bigul Kisan entered a piece of land with his plough and his ox and was beaten up by the henchmen of the local jotedar. On May 24, Inspector Sonam Wangdi led a police posse to Barajharu to arrest peasant leaders. He died in a rain of arrows.

The next day, the peasants called a meeting at Prasadjote in Naxalbari. The versions differ on what exactly happened, but 11 people died in police firing, including seven women and two children. But by this time, the dream of a Maoist revolution of peasants and workers had spread far beyond this one hamlet. An anonymous poet wrote on the walls of Calcutta: "Amar bari, tomar bari/Naxalbari Naxalbari (My home, Naxalbari/Your home, Naxalbari)", and the violent movement sweeping Bengal had acquired a name.

Revolution is not about killing a traffic policeman, it's about armed struggle, believes Kanu Sanyal.

Some distance from where the firing took place stand three busts: Lenin, Stalin and Charu Majumdar. The bases of the busts read: "Established by Leader of Heart Respected Com. Mahadeb Mukherjee CPI(ML)." Pavan Singh lives a stone's throw from the busts: three earthen huts with a courtyard and a tiny patch of land which he tills. "I saw my mother being shot down; the ground was a river of blood," he tells me. Singh is still committed to the revolutionary cause. The trouble is, the roads to revolution seem too many. "We, the CPI (ML) Mahadeb Mukherjee group, are the only true Communists. We follow the CM line. Kanu Sanyal now talks of standing in elections. Anyone who talks of votes has deviated from the true path, because then you are working within boundaries set by the powerful classes. He is not a true Communist."

And what is that? "A true Communist is not someone who took part in one movement; he is a man who never does anything wrong in his whole life, who remains committed with every living breath to the cause of revolution. " The trouble is, they are dwindling in number. "After Stalin, Russia was taken over by mensheviks," says Singh's compatriot, Anil Sutradhar. "Khrushchev and Reagan created the Cold War myth; in reality, they were in cahoots to destroy the one true socialist state, China. The powerful have always propagated myths to keep the proletariat divided. They even say China attacked India in 1962." Why is that a lie? "Because China is a socialist state. A socialist state cannot commit an act of aggression." I forget to ask him about Tibet.

In the months following the Prasadjote firing, angry peasantry attacked and killed jotedars and forcibly occupied land. They were led by CPI(M) men like Sanyal. And the brutal police operations that managed to crush the revolt by late 1968 were also ordered by CPI(M) politicians; Jyoti Basu was the home minister. All CPI(M) office-bearers who had any sympathy for the Naxalbari uprising were expelled and formed the CPI(ML), but the movement had already spread across Bengal. By the time it subsided several years later, the police and paramilitary forces had killed thousands of young men and women—the best and the brightest of an entire generation, even their corpses thrown into secret mass graves. "When Jyotibabu became home minister, he came here. Jangal Santhal's wife and I garlanded him," says Singh. "A year later, he ordered the police to kill and torture at will to suppress our movement."

In fact, Basu approved the massive police action called Operation Crossbow the same day—July 5, 1967—that the Chinese People's Daily hailed the Naxalbari uprising as "Spring thunder over India". Sanyal was arrested in October 1968, and CM died in police custody in 1972. "Our movement failed because you can't liberate a country by killing individuals," says Sanyal. "You kill a landlord, his son will come. You just lose the people's support. The revolution can come only through an armed mass struggle. But CM said mass organisations like trade unions were of no use, that unless you wet your hands in the blood of a class enemy, you are not a true Communist. I don't think you become a true Communist by killing a traffic policeman."

Nitai Dey, who says he has always supported the CPI(M), was a young man in the fiery days of 1967-68. "What CM and Kanubabu wanted to achieve here—ending the exploitation of the peasantry—had every common man's support. But when they started killing individuals, people saw it as terrorism, not true Communism. I don't think true Communism has anything to do with killing a traffic policeman." My childhood memories well up: Calcutta under Section 144, the sound of distant gunfire, a trader I saw being killed in broad daylight from the window of my school bus, reports of innocents slain by revolutionaries, innocents slaughtered by police.

But talking of votes does not a 'true Communist' make, counters a more radical Pavan Singh.

Children play near the three busts. Do they know who these men are? They are shy, smilingly nodding their heads. Then a little boy comes forward. "Some people broke that statue," he says, pointing to the CM one. "It was a rainy night. They broke its head." "They thought they could wipe out the man's philosophy by breaking his statue," says Sutradhar. "We had it rebuilt." He guards the sculpture now, day and night.

It's by the statues that I meet a young man called Manas Singha and hear of Kamtapur. "I am not a Bengali, I am a Kamtapuri," he tells me. "I have my own language, my own culture. This was Kamtapur before people from South Bengal over-ran it. Today even history books don't mention that glorious kingdom." He speaks in what he says is Kamtapuri, which sounds suspiciously like a dialect of Bengali to me. "Well, then Bengali must have come from Kamtapuri, for it is an older language."

A few miles from Naxalbari is the modest home of Atul Roy, the leader of the Kamtapuri movement. A dozen young men idle in a small room. "We want six districts of West Bengal to form the state of Kamtapur," says Jharua Burman. "Ideally, it should also have a part of Nepal, parts of Assam and Bihar and Bangladesh. Over the centuries, people from South Bengal have taken away our land and turned us from a rich culture into a race of day labourers. We build the buildings here, we build the bridges, but they are owned by Bengalis. It's been going on for just too long."

On the way to Roy's house, I saw posters with the photo of a CPI(M) activist who was recently murdered, allegedly by Kamtapuri militants. "Whenever there is a murder in North Bengal, they blame the Kamtapuris. But do they have any proof?" ask Burman's friends. "What we want to know is how this CPI(M) activist, who was living in a tin shed till some years ago, amassed property worth Rs 4 crore?" Is this a denial of the Kamtapuri role in the murder? I don't know. "The other day, Buddhadeb Bhattacharya said it is time to whip the Kamtapuris into submission. Let's see if he can do that. We are ready."

Tea estates in the area are already getting extortion threats. A police officer tells me: "These boys have linked up with every terrorist group in the northeast: ulfa, the Bodos, the Naga rebels. They are being trained in ulfa camps in Bhutan and they also use hoodlums from the nearby Kishangunj district in Bihar." I look at the faces in Atul Roy's room: boys wanting to be men, college students, young men who see only a bleak economic future for themselves. So much blood ready to be spilt once you add the seductive ethnic twist to problems that are essentially economic. So much blood ready to be spilt on these beautiful plains, where the mountains are just out of sight.

But didn't the peasants' war in Naxalbari solve anything? "A lot of development has happened since then," says panchayat member Dilip Oraon. "Everyone here has land to his name now." When I tell him this, Sanyal responds with a tired smile. "Yes, land distribution has happened but is the land with the peasants? Anyway, what can a poor peasant do with a small piece of land? He does a distress sale and becomes a sharecropper again, it's just that the name of the jotedar is different from the one in 1967. Nothing has changed."

Indeed, someone driving down the highway between the verdant tea estates with rows and rows of men and women plucking leaves, singing to themselves, would never imagine that the situation in the gardens is possibly worse and more incendiary than in 1967. Today, most estates in the area are owned by Calcutta-based fat cats who are doing to tea what they did to jute: suck out every paisa you can without investing a penny. Nothing is spent on replantation; estates here have tea plants which are 90 years old. Labour rights exist only on paper. Minimum wages are not paid. Provident funds are fictional. It is common practice to sack workers before they complete five years on an estate, because that makes them eligible for gratuity. According to the law, tea workers get cheap rations. A few months ago, plantation owners unilaterally changed the rules so that now, if a worker is absent for a single day, he has to pay 345 per cent more for his rations! If he is absent for three days, he pays 1,037 per cent more, and six days, 2,074 per cent more! On July 21, 1999, a new owner-worker agreement was signed for the tea gardens of the Terai-Doars-Darjeeling region with Jyotibabu as witness. Till the middle of November 2000, when I visited Naxalbari, nothing in this agreement had been implemented there.

Sanyal says that he has organised unions in 16 nearby tea estates, and the number is growing rapidly. "For a revolution, you have to raise consciousness. For that, we need a true Communist Party. I am in talks with many Marxist parties and trying to build a united real national Communist Party that has a programme, not just words. But the nation will not wait for that party to be formed, will it? There is much to be done here, now." "We have bought the union leaders from all the big parties," a tea estate manager tells me. "But when I offered 5 kg of our best tea to Kanubabu as a gift, he said, 'Tell me where your tea's available, and I'll go buy it'." But in Naxalbari market, a cynical shopkeeper tells me: "Today, people support politicians who have money. Kanubabu has no money, so he has few followers."

"Kanu Sanyal is organising trade unions now," sneers Pavan Singh. "In the original movement too, he diffused the issue by harping on land redistribution. We were not fighting for land, we were fighting for national power." How is Singh going about it? "We have set up revolutionary committees in villages. Their activities shall be coordinated to form an alternative government." Behind Singh, his family members go about their business, and his wife makes tasty black tea with a touch of ginger.

The question of change. Sanyal laughs. "Yes, things have changed. When I went to jail in 1968, no one here cut trees, there was no smuggling. When I came back from jail 10 years later, on the bus to Naxalbari, I was about to give up my seat to a lady who looked clearly pregnant, and my companion said, don't be a fool, Kanuda, she's just a smuggler, carrying stuff underneath her saree. Some time later, I went to Panighata forest and found there was no forest! I asked a passer-by; he smiled and patted his tummy. They had eaten up the jungle! Did you notice the four men who went by behind your back silently 15 minutes ago, carrying illegally cut timber? All this is change definitely, but for the worse."

But in Naxalbari, that cusp between mountains and plains, the dream of revolution, of a just society, only gets stronger. "Just because the crop failed once, does the farmer not plant seeds next year?" asks Sutradhar. "Our first attempt failed, maybe the losses will be even greater the second time around, but the revolution will come. It has to." "We are one crore people. If five or six lakh Gorkhas can get their own Hill Council, why can't we have our own state of Kamtapur?" asks Jharua Burman. "Every man, woman, schoolchild is with us. We will get Kamtapur."

Kanu Sanyal has broken his foot. He is in pain, but that is nothing new. What are his dreams? He is frail, 72 years old, a short, dark, unassuming and courteous man who has seen too much. "Revolution is not instant coffee. It may come in two years, it may come in 30. It may spread like prairie fire, it may be a slow process. Meanwhile, there is so much to do. Before I die, I hope that I can make a difference to the lives of the poor, oppressed honest people in the Naxalbari region." The pitch dark countryside beyond the flicker of the lantern seems like the inside of a tinder box waiting for a spark.