When we think of patriarchy, the concept of spirituality is not the first thing that comes to our mind. There is a general tendency to associate religion with patriarchy and spirituality with something that relates to the sublime. The reason for this is self-evident: spirituality is an individual’s journey, while religion deals with a community’s journey—and hence subject to collective phenomena. But when discussing patriarchy, one must try to appreciate the relationship between spirituality and religion; just because spirituality provides an individual lens, it cannot be disassociated from the collective lens of religion.

One cannot belie the fact that, around the world, one can see that patriarchy manifests most powerfully through spiritual discourse—as spiritual discourse is often presented as the truth. It is classified as metaphysical truth beyond the reach of science. It thus comes to serve as a powerful authority that governs the way in which people form their approach to the world at large.

Take for example the Christian doctrine, which says God created man in his own image, and then created a woman from the man’s rib. This gives man the role of the superior between the two genders. This story, where the man is given the primary position and the woman the secondary position, comes from the Old Testament, which is also known as the Jewish Bible.

In the New Testament, we learn of Jesus, who had many women among his followers. Indeed, he had a very close relationship with his mother, named Mary; the former prostitute who was called Mary Magdalene; and the sister of Lazarus, who was also called Mary. More importantly, it is to these women that Jesus appears first, after his resurrection.

Yet one finds that the Catholic Church is dominated by men and there is no sign of women within its hierarchy. Only priests and bishops can conduct the sacraments of the Eucharist, Penance, Confirmation and Anointing of the Sick. Only bishops can administer the sacrament of Holy Orders, by which men are ordained as bishops, priests or deacons. The order, referring to those who exercise authority within a Christian church, was established by Peter. There is no role for women, let alone in any higher position of power.

The same is seen in Islam: while Islam talks of equality and brotherhood among men, women remain at an inferior node on the tree. In the Quran, we are told God talks of woman, but refers to no one by name, except Mary, mother of Jesus. Women are expected to cover their face with the hijab, as women veiling themselves are considered noble. In some Muslim communities, women also have to go through genital mutilation as a sign of the covenant with God.

Gender roles in Islam are guided by two precepts: firstly, there should be spiritual equality between women and men; and secondly, women are meant to exemplify femininity, and men masculinity. The emphasis Islam places on the feminine/masculine polarity results in a separation of social functions. In general, a woman’s sphere of operation is the home in which she is the dominant figure—and a man’s corresponding sphere is the outside world.

Although in the West, people equate the hijab with patriarchy, ironically, the most radical left-wing endorses it and calls any attempt to ban the hijab or any argument against the hijab as Islamophobia. This creates a perplexing uncertainty as to what religious freedom truly is. It yields the question: are we allowed to express patriarchy through religion, and will patriarchy be acceptable if it is expressed through religion?

In Sikhism, one again speaks of equality between genders, but one sees very clearly that the entire Sikh doctrine is dominated by men. All the gurus who interpret the word of God were men. In the modern day, the raagis of the gurudwaras are men and the ones who form the administrative tiers in the gurudwaras are mostly men. Women play a secondary role, at best via lip service or through tokenism. In Sikhism, God has no gender, but we still see men privileged over women, even in the social structure of each religious establishment.

It’s the same in Jainism and Buddhism—both religions with no concept of God. They see the world as timeless and unending, and their focus is on the metaphysical levels; but here again biology plays a very important role. In Jainism, there are more female nuns than male monks and yet, incongruously, men dominate the monastic establishment. The supreme sages are visualised as men. The religion’s precepts inculcate the doctrine that the female anatomy does not allow women any chance of developing a higher status. It is only after being born a male and acquiring a male body in a future life that a Jain woman can attain the highest state of Kevala-gyana.

In Buddhism, presented as egalitarian around the world and said to espouse every rational doctrine, the Vinaya Pitaka text documents a strong misogynist view of how monks have to stay away from women. The reason: women are viewed as temptations that seek to destroy. Personifying appetites and compulsions, they must be kept away from the monastery. Although Buddha allowed women to become nuns after initial hesitation, men dominate the entire monastic order even today, with supreme leadership always given to a male. It took nearly a thousand years after the Buddha for Buddhism to acknowledge a Buddhist goddess—Tara is first mentioned only around the 6th-8th century AD. And this mention spread mostly in places where Tantra became powerful.

Thus, we see that monotheistic egalitarian doctrines such as Christianity, Islam and Sikhism as well as atheistic doctrines such as Buddhism and Jainism do not typically favour women. So, it comes as a surprise to many Indians that when the Sabarimala issue is raised, it is seen as something specific to Hinduism and does not become part of a continuum of spiritual misogyny where women are kept away for various reasons.

In Sabarimala, the argument is that the deity is a bachelor God, hence women must be kept away. But Hanuman too is a bachelor God and, at one time, women avoided worshipping him, but not anymore. In many parts of India, especially in the north and the west, Shiva’s son Kartikeya is seen as a bachelor God and warmonger, and women stay away from his temples. However, in south India, where Kartikeya is known as Murugan, he is seen as a romantic, married God, and women participate in his ritual festivities.

Thus, we find diversity in Hindu beliefs. The question is: if diversity was allowed, allowing for misogynistic and patriarchal practices in the days of yore, is it wrong to condemn them in the 21st century and homogenise them in the name of gender equality?

In the Tantrik traditions of Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism, occult powers are obtained by staying away from women. By withholding semen within the body, a certain capability advances through the spine, thereby giving rise to special powers known as Siddhi. These allow a man to fly up through the air, or walk on water, or increase in size and shape. These are said to be the acquired powers of the Nath jogi, who stayed away from women.

In Nath jogi lore, we hear the story of banana orchards (kaladi vana) where women lived and no man was allowed to enter. Any man who entered the space turned into a woman, which, in turn, frustrated the women, because they needed a man to bear children. The only men who could enter the orchards were those who had complete control over their senses, such as Hanuman and Nath jogis. But, to keep their spiritual status intact, they would not touch the women even after entering the orchards, frustrating the women further.

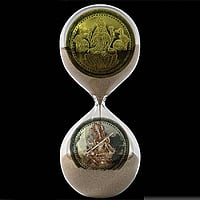

Stories like these became popular in the 9th and 10th century AD in India, which established the belief that association with women kept one tied to the material plane and withdrawal from them would elevate one to the spiritual. It is at this time that magical properties came to be associated with semen and menstrual blood. It is in this time we discover the construction of Tantrik yogini temples, in Odisha and Madhya Pradesh, where a circle of women are worshipped, in mysterious occult rituals, that gave power to the man who sat among them, engaged with them, but did not lose control over his senses and maintained his celibacy.

One must take these ancient beliefs towards women in the appropriate context as they occur in various spiritual and religious traditions. They contribute to patriarchy and misogynist cultures across the world. In the name of religious freedom, people are demanding the right to be patriarchal and misogynistic. So Christian fundamentalists in America are demanding that queer people be kept out of churches. And Islamists are demanding that Muslim children studying in Europe wear the hijab to school. If freedom is a good thing, surely freedom to discriminate on grounds of religion is a good thing too?

It makes us question the nature of laws in this world, and of what is considered appropriate social conduct. In a cultural context, must people have the freedom to oppress other groups of people? This is a complex question, which perhaps even a court, with the most venerable of judges, cannot solve to the satisfaction of all groups.

Devdutt Pattanaik writes on ancient Indian scriptures and mythology