Of late, my LinkedIn account is a regular recipient of an unexpected kind of proposition. Business-like in tone, promising customer satisfaction, are male sex workers catering specifically to women. Armed with a clear rate card and corporate tone, these provide a detailed menu—from erotic massage to cunnilingus to penetrative sex. They are a stepped up version of accounts on Tinder, self-describing as gigolos, alongside Tinder profiles of Tarot card readers claiming to predict your romantic future, thereby revealing, perhaps, the twin quests of intimacy.

This is how I connected with Amit (name changed on request) a nondescript, but neat looking man in his 30s with an unassuming manner. A software engineer by day, he said he liked servicing women, as it gave him a certain pleasure and peace to see them happy. “Women should be loved, you know.” This may have been an affectation, but to me, it sounded entirely sincere.

Did he have a girlfriend? Sometimes. Were his clients regular? Sometimes.

In most accounts of gigolos, clients are always older women married to rich, travelling men. But Amit surprised me by saying most of his clients lived in Mumbai’s Western suburbs, were aged between 28-35, working in media and corporate jobs. “I think they are not from the city. They live alone and don’t have time and maybe they don’t meet good men,” he offered as explanation. “But they are clear about what they want. Afterwards, we also talk for some time, as I am interested in their work too,” he added.

There was something unexpectedly relaxed and collegial about the account. At the best of times, assumptions are a dodgy proposition—but never more than in the world of sex and desire, unpredictable and ungovernable by definition, half concealed and half revealed by nature. And certainly not in the present moment, as most stereotypical ideas about Indian sex lives visibly do not apply.

Just this last week, I’ve sat next to a young Indian woman on a plane to Bangkok who complained about her bad marriage, listing amongst her several issues that, “our sexual relationship is also not good; we don’t have sex for months at a time”. It’s not that she shared this with a total stranger, but that she did so matter-of-factly, conveying a natural sense of sex being part of a decent, happy life.

Two days later, I met an Indian man in a bar in Yangon/Rangoon, who informed me that he was an entrepreneur. “Isn’t everyone?” I thought to myself, until he added that his new start-up was a sex toy store. The government may want to expunge the word sex from sex-education. But Indians are talking more about sex, starting more sex-related businesses, consuming more sexual goods and services than ever before, without euphemisms.

Numerous sex surveys done since the late 1990s have tracked these shifts in sexual culture—from dating to pre-marital sex to the decreasing expectation of virginity. The discernible narrative arc of a decade of such surveys is this--sex and committed relationships are drifting apart. Whether people call it casual sex, premarital sex or dating, they no longer pretend that a committed relationship is no longer the declared prerequisite or rightful location of sex.

In a 2011 survey in this magazine, on casual sex, 32 per cent of respondents had a passing sexual encounter with a complete stranger. Of these, 38 per cent had lasted no more than an hour, while some had lasted a few days. A third, were initiated by women. One-third of respondents had had over five one-night stands in a three-year period. But perhaps most interesting of all, a fair percentage of respondents claimed that they would forgive their committed partner for a casual sexual encounter. Nothing is more indicative of the fact that the human need for sex is being accepted and acknowledged with far less drama than before.

The Libido is definitely out of the closet and happily on fire. One of the things it is doing through its unstoppable energy, is, as always, creating new markets. For, sex and the bazar are old bedfellows. Even while commercial sex work, often called prostitution, continues to struggle for recognition as work, a large number of people do earn their living from sex today.

The dating app market (as distinct from matrimonial sites) is currently valued at $130 million and growing, with about six million singles in India having joined dating sites, according to dating site reviews. Tinder India claims to have 14 million swipes a day (up from 7.5 million a day in September 2015). Truly Madly has about two million downloads with 1,00,000 active users, who on average spend 42 minutes a day on the app in about eight to ten sessions. Of these users, 40 per cent are aged between 18-26 and mostly from smaller cities and towns.

The boisterous new kid on this block is the sex toy business, currently estimated at Rs 3,000 crore and expected to touch Rs 9,000 crore by 2020. New players are entering the field—biggies like I’m Besharam and That’s Personal, mid-sized players like Kinkpin.in and Its Pleazure, and more niche feminist inflected groups like Love Treats and, of course, the gentleman I met in the bar. They offer everything, from edible underwear to floggers, vibrators to handcuffs. A recent article revealed an unexpected niche market for second-hand (or foot) women’s shoes, stockings and socks on sites like Olx. The buyers—men with a shoe or socks fetish, of course.

OYO has made finding inexpensive hotels easier for people who don’t have a place, or who can’t use the place they have in the case of extra-marital affairs, or maybe for loud sex in small houses. Stayuncle.com goes one further by connecting hotels willing to rent rooms by the hour to couples for unambiguous reasons.

The digital changed the intimate in Indian life as soon as it entered homes in 1998. According to We Are Social, India has about 350 million active internet users, of which around 289 million active users belong to urban areas. A notable percentage of these access the internet on their mobile devices. Under 25 per cent of these users are women. The internet altered something fundamental in the structure of Indian personal life. It afforded Indians privacy, otherwise very hard to get in a family-oriented space, without having to make a radical break with family, to which Indians continue to feel connected. Where this once might have constrained sexual journeys, keeping them shadowy or shameful, it now became possible to explore this personal space, both literally and metaphorically. You could be at home after dark as mandated, but be anywhere in the world talking to anyone about anything—on your phone or laptop. This has flagged off a journey of random play—roaming about the by-ways of the internet, chancing upon others who share your sexual fantasies, finding names for your sexual preferences, charting new sexual and romantic destinies.

Its notable impacts was the LGBT world, as queer folk found lovers, friends and community via the internet in an exciting yet relaxed manner, making something that was once never discussed a routine part of the mainstream discussion today—no matter what the law says. And it is to the gay location based hook-up app Grindr that heterosexuals owe the joys of Tinder and its ilk.

Sexual communities and expressions have only grown with time. The BDSM community has become more defined, with groups like the Kinky Collective exploring new understandings of consent and mutuality available in the kinky lifestyle. The wonderful project, Sexuality and Disability, creates a range of discussions on sexual possibilities for those with disabilities. Indian Aces is a fledgling community of people who identify as asexual or demisexual.

Along with rendering many identities visible, it has also been a journey of simple articulation—of cyber sex, phone sex and sexting, of talking sex, not just about sex. With an increasingly unlimited ability to play out fantasies from a safe space behind the screen, before actualising these IRL, or In Real Life, Indians have learnt about their own sexual appetites and preferences, setting off a full-scale socio-sexual symphony of experiences and self-discovery.

On Agents of Ishq, a digital platform I founded a year ago, the number of narratives that have tumbled in—tender stories of first kisses, exhilarated accounts of posing in the nude, the joys of masturbation, the need for regular STI check-ups, the beauty of the penis, the shifting relationship between body hair and sex, explorations of ethical polyamoury and determined monogamy, the joys of bisexuality—all reveal a steaming, teeming interior life and people restless and excited about sharing their sexual journeys and discoveries, as well as and what that has meant for their understanding of life and themselves.

An entire generation has grown up taking this highly diverse digital space as a natural environment. Even as ties of community loosen—families grow more nuclear, people migrate to other cities for work, new economic and social mobility redefine the emotional and the personal as much as the social—so individual journeys, including the sexual, have multiplied. Now everyone’s life is a self-scripted movie, playing out on their individual screens as they travel further afield to search for personal sexual fulfilment.

In 2010, Manjima Bhattacharjya and Maya Indira Ganesh interviewed a group of urban women on how they used the internet, as part of a study called Erotics: Sex, Rights and the Internet. They found, “Young women were vocal about the excitement in making friends with strangers online through chatting, and social networking sites allow them a certain freedom in being able to mingle with the opposite sex and display themselves wearing ‘sexy’ clothes.... This gives them a sense of agency and thrill.” The thrill overrode the risk of discovery by family or known people and possible consequences, including restricted access to the internet.

Today their numbers have grown, and any number of Facebook pages and accounts bear testimony to the adventure of being appreciated for such ‘sexy’, semi-clad photos—in a sari and petticoat or wrapped in a post-bath towel—dozens of admirers, male and female, write words of appreciation below: ‘looking hot/sexy/butiful’. Poonam Pandey may have turned this peekaboo eroticism into a business model. But for many women, it is the frankest flowering of self-expression, which is both sexual and affirming, a kind of public presence in the world. Also proliferating is the number of amateur porn videos Indians are uploading to diverse porn sites. “Tired of having your intelligence insulted by set-up videos, surreal plots and corny-fake titles? Tired of getting what was supposed to be a home made video of an intimate moment between a REAL couple and finding out it was a set-up shoot?” asks one site, then adds, “Your search ends here”.

Actually your search begins there, because there are hundreds of amateur videos on each site. The thrill of exhibitionism is only a part of it. Even a casual glance uncovers a peculiar kind of innocence or ‘realness’ attached to the videos. It suggests a certain tender confidence, the display of real bodies, so far away from mainstream porn’s pneumatic, overblown bodies, having relatable sex, rather than predictably categorised sex.

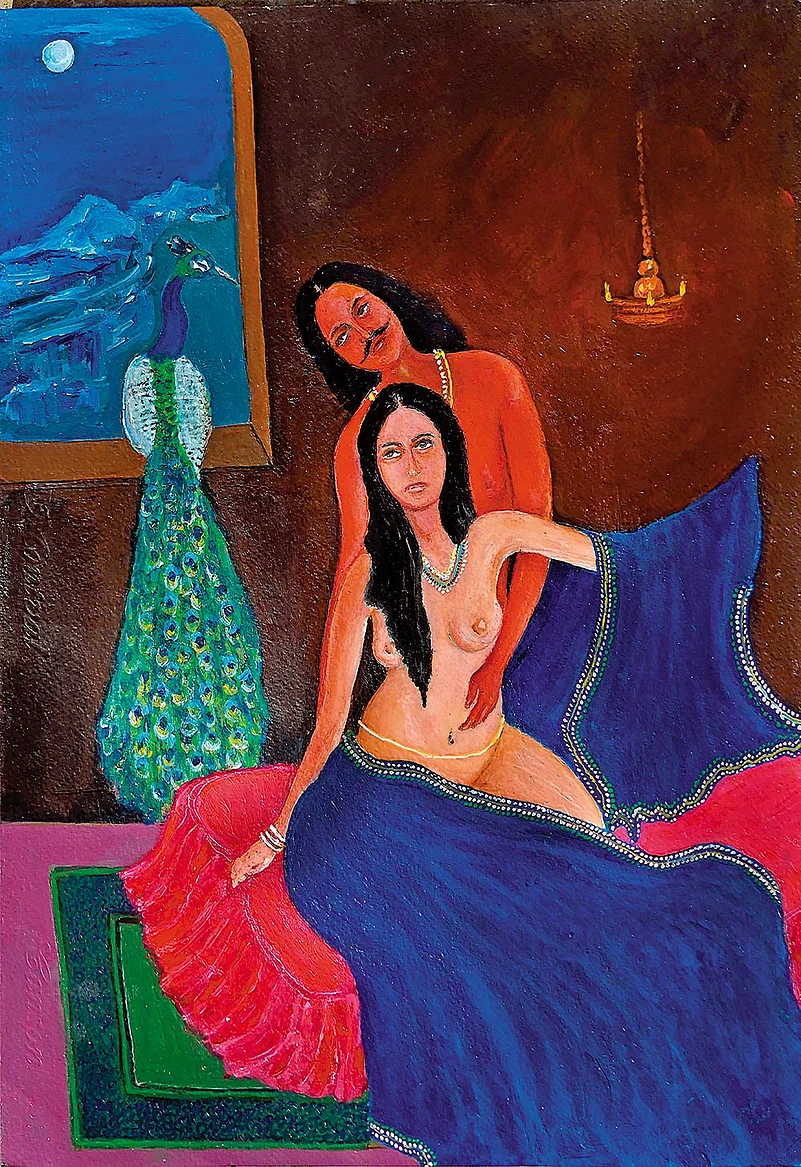

A Raja Ravi Varma painting on Radha-Krishna love inspired contemporary artist Narendra Raghunath to go for this 2016 work. Brown man’s aspiration for a fair woman is not limited to mythology, he notes.

When fantasy and reality merge, it is like a declaration of independence—in this case, of a personal relationship with sex. Just a bunch of people having good, unclean fun. If the porn market won’t give lovers what they want, why, they’ll just make it for themselves—and thereby, one day, create a new market. After all, it is always that which is somehow outlawed, the space at the margins, where new ideas are worked out before they spread through the world like a virus and transform it. When the infidelity-based site Ashley Madison was hacked it revealed Indians had one of the highest sign-ups to it. Given how many Indians there are in the world, perhaps it is time to stop exclaiming at numbers. And what, after all, is notable about infidelity, a behaviour as old as marriage?

What is new, though, is a recently reported trend—that of couples involved in relationships outside their marriages going to couple counsellors. It is almost as if new kinds of relationships are being institutionalised at an accelerated speed, giving emotional life new meanings, new validities.

So, if so much has changed, what hasn’t? The travails of dating app use provide some clues. Female sign-ups to dating apps remain relatively low. The reasons are many—but are deeply rooted in the differences between how men and women think about casual sex. Most surveys, as well as cultural evidence, show that a persisting disrespect for female sexual agency and consent exists. Simply put, it translates into the idea that women who are open to sex are automatically seen as available for sex to anyone who approaches them. The idea of consent, as something negotiated in a mutually enjoyable manner, and eventually linked to the larger idea of consent in the world, is highly underdeveloped. This can make the dating app space not only occasionally hostile and abusive for young heterosexual women when they refuse someone, but also dissatisfying as a place to play, though not without its success stories.

In other words, gender remains a sticky issue. More and more women explore their lives in every way, finding greater freedom and self-expression, sometimes through sex and sometimes to sex. The sheer effervescence on display at Delhi’s recent Queer Pride event was as much about freedom as it was about the expansion of Pride to include the idea of queerness beyond divisions of gay and straight, as an idea which recognises desires and relationships, where marriage may be present, but is no longer central, and certainly not in its traditional, heteronormative image.

In this context, a significant percentage of heterosexual men, still clinging to patriarchal notions of gendered and sexual roles, are the wallflowers at the Big Indian Sex Party—anxious and paralysed, misogynist and toxic, self-hating or self-doubting. In different ways, they are struggling to cope with these changes and remain an unaddressed population who need to redefine a more joyful, perhaps more fluid, masculinity for these times.

This imbalance also manifests in matters of safe sex practices. Emergency contraceptive pills, like the I-pill, are often touted as a great aid to freer sex for women. Their rising use as a routine contraceptive, rather than an emergency morning after pill, when considered alongside dropping condom use, is far from reassuring. At a recent panel on how dating apps have changed erotic life, Sachin Bhatia CEO of Truly Madly suggested that women are searching for more committed or meaningful relationships, as opposed to men who largely seek casual sex. He was loudly contradicted by women in the audience, who averred that they too were often looking for uncomplicated, physical pleasure. Just that they also wanted it to be with mutual respect.

It’s possible that many women simply say serious relationships are what they want, or that it is what they eventually want, with fleeting relationships and encounters preceding marriage not taken so seriously, because moral judgment of women’s sexual agency is still pervasive. Or that they recognise that many Indian men display greater respect for sex with women they are committed to. More simply, it demonstrates the elusiveness of clear definitions when we step away from the private sphere of sexual desire to the more public space of relationships, which carry certain social meaning.

In response to the articulated social preference for “meaningful relationships”, many apps have been at pains to present themselves as not simply sexual. They provide more verification, claiming this means they will attract more ‘serious’ and ‘better quality’ potential matches, but results remain mixed.

Tinder, whose abiding image is of a place where hooking-up is the central premise—where sex is near the table, if not definitely on it—also tried to recast itself in India as a place where people generically connect. Their film, presenting Tinder as a sanitary app you could take home to mom, earned more eye rolls than eyeballs and made no dent in its image as hook-up headquarters. In the end, Tinder, with its extremely open-ended, minimal and voluntary verification platform, continues to be the most popular. While this may point to an Indian enthusiasm for casual sex, it also relates to the fact that people use dating apps in multiple ways. Some do it to kill time at traffic lights, others, to make friends. A few, even to network. Some are looking for love, some for an unending series of mini affairs, extra-marital or regular, some for validation, some for someone with enough shoes to orgasm into and others for they don’t quite know what.

Sometimes, the same person is looking for some or all of the above. The less prescriptive the space, the more likely people will play in it, notwithstanding risks. People simultaneously long for the gossamer connections and intimacies that we call love and the glittery excitement of sexual play and exploration with low stakes.

Perhaps it is only colonisers, who love anthropological catalogues, and corporates, who love excel sheets, who expect this to be otherwise. They prefer subjects and consumers to behave in homogenous and hence controllable ways. The world of sex and desire is radical precisely because it defies this, pulses with a polyphony and libidinal caprice, upends categories and alters norms, ferrying people from one cultural phase into another.

Change happens in waves, not in one go, so various tendencies will always co-exist in any society at any time. But, confronting the co-existence of both, the sexed-up and the prim, the media too loves to wag its finger at its favourite cliche—‘hypocritical Indian society’. While cultural double standards doubtless exist, this notion of hypocrisy seems to draw on the tired polarity of tradition, i.e. repression versus modernity, i.e. liberation.

Think for a minute about India’s diverse sexual cultures. The Kama Sutra, aimed at gentlemen of leisure, and the Sattasai, poems about love and longing among common men and women (‘Who is not captivated by a woman’s breasts?/That like a good poem are a pleasure to grasp?’). Or 18th century Deccani texts on aphrodisiacs and the Gita Govinda, drenched with desire (‘Sagely its deep sense conceiving/And its inner light believing’). Or Urdu Rekhti poems, featuring smoking hot neighbours and queer relationships of all intensities; also, queer identities of all kinds in mythology, as also, Khajuraho and Chola bronzes and pattas, where sex positions nestle naughtily behind the Dasavatara.

Think of lavnis and thumris laden with husky innuendo and a million folk songs where sex is a matter of fun, longing or just a rite of passage. Heck, think of a whole nation enthusiastically crooning along with Nazia Hassan, Har kissi ko chahiye, tan man ka milan, in 1980. Perhaps, it is the opposite. Sexily wriggling out from under a monochromatic cloak of colonial prudery lined with Brahminical censoriousness, perhaps Indians are simply going back to tradition. Finally, sexually sanskari, that is.

(Paromita Vohra is a filmmaker and writer and the founder of Agents of Ishq, a digital project on sex-ed and sexual culture in India)