Do I dare

Disturb the universe?

The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,

-- T.S. Eliot

We are all witness to the difficulties faced by the Alternative Law Forum and Pedestrian Pictures, and other agencies based in Bangalore, who have organized in their city the recent festival, Films for Freedom (FFF). This film-festival is a continuation of Vikalp ("The Alternative"), a successful set of screenings that came in response to the censorship faced by Indian film-makers at the last Mumbai International Film Festival (MIFF).

Documentary film-makers like Sanjay Kak and Amar Kanwar, Rahul Roy and Saba Dewan, Rakesh Sharma and Anand Patwardhan, have been targeted at both MIFF and FFF, and in retaliation have mobilized the entire documentary community not only within India but also more widely in the Southern Asian region, first to organise Vikalp in Mumbai and then to speak out at FFF in Bangalore. Both events have generated a tremendous turnout, by directors as well as by critics and viewers, taking on the flavor of mini-movements.

Censorship of films, intimidation of film-makers as well as their audiences, threats to the safety of cinema-halls as well as alternative screening venues - these kinds of undemocratic and downright lawless tactics have been used by both governmental and extra-governmental forces.

It has not mattered whether the site for such challenges to the freedom of expression has been one supposedly liberal city or another, whether the government at the center has been the BJP-led or Congress-led. The past year has been a telling one for the public record on film-censorship in this country, regardless of dramatic changes in the larger political climate.

What does this indicate?

It appears that the impulse to curb free speech is not limited to authoritarian and patriarchal cultures such as that prevalent in a city like New Delhi, nor is it peculiar to political parties of the right. The reflex of those who rule, anywhere, from any ideological camp, is to prevent people from speaking out. If some people from among the People seek to express their dissent against or rejection of the ruling structures through literature or the arts, then these individuals come in for naked demonstrations of power that can go all the way from the banning of their artworks to death threats.

What is the driving impulse behind censorship? What forms does it take? How have fellow-citizens, especially artists, film-makers, activists and writers, done battle against it?

On February 14 2004, Valentine’s Day, new media practitioner Shuddhabrata Sengupta, of the Raqs Media Collective, organized a forum to protest against censorship, at Sarai-CSDS, New Delhi. Speakers included the legal activist Lawrence Liang of the Alternative Law Forum, the collective of documentary film-makers who organized the ‘other’ film-festival in Mumbai late last year, ‘Vikalp 2003’, and left-secular feminists like Tannika Sarkar and Shohini Ghosh, who talked about the banning of the work of Bangladeshi novelist Taslima Nasrin.

My brief was to speak about censorship in academia; others gave reports from the fields of law, film-making, and literature. The day yielded an intense conversation spread over eight hours. At first I was heartened by the passion and eloquence of the participants as well as the audience; I was also amazed by how well the whole event came together. Only on some reflection did I realize that the coherence of the day’s proceedings was a sign of something alarming - censorship has become a reality in several walks of our public life. We were all making sense to one another and comparing notes so animatedly precisely because we had all had similar experiences, or had noticed in our respective fields similar phenomena.This was cause for worry, not celebration.

On further reflection, it struck me that while the discussion at Sarai on 14/02 revolved mostly around forms of expression and the freedom of expression, what is really at stake, with censorship, is not so much expression itself, but the perceptions and reactions that form the referents of expression. This means that what the censor is actually getting at is not what a writer, a film-maker, a scholar, or indeed any citizen says, but what s/he must be seeing, hearing, or feeling in order to come out and say those things.

Thus the real objects of censorship are not words, but Arundhati Roy’s persistence and Taslima Nasrin’s desire; Medha Patkar’s anger and Amar Kanwar’s concern; intelligent and sensitive people everywhere noticing their environment and responding to it with insight and honesty. Censorship would like to shut down not mouths, but minds. Censorship would like to contain not just the production of works of art and works of knowledge, but the very emotional and intellectual impulses that go into such production. This is cause for even more worry.

After that memorable but disturbing day at Sarai, Sanjay Kak was good enough to show me his award-winning film, Words on Water, which followed the Narmada Bachao Andolan at the height of the anti-dam movement. In this documentary, his camera is unobtrusive, but unflinching. It misses nothing.

A couple in a boat, the woman pointing to the swollen waters that cover her lost fields. Exactly here, she announces in the middle of what is apparently the river Narmada, is my property. You can flood the earth but not the woman’s memory. A great crowd of protestors at a dam site, confronting an indignant government official. He is shouting with fury. Not because the people are threatening, not because his truck-loads of armed men cannot manage the situation, but because he is accused of being an agent of multi-national corporations. Hundreds of thousands of tribals and villagers stand to have their homes and lands be inundated if the height of the dam is raised, but the official is angry that his dedication to the nation and his respect for the law are being questioned.

You can take away someone’s livelihood, even his life, but you cannot impugn the integrity of an honest man. Sanjay Kak must have special eyes, to catch these scenes as they unfold. Kak’s eyes could be dangerous to a ruthless state.

Now he has shots of Medha Patkar, as police personnel try to remove her from some place or other that she is not supposed to be. Her body is resistance itself, sheer uncooperative mass, as though lacking muscles to walk away, to flee. No expression animates her face. "Main nahin hatoongi,’ she says calmly, "I will not move." Implacable human will. I will not move. She looks her captor in the eye. It is as though silence falls for an instant, everything goes quiet, there is Medha saying ‘no’ and the policemen of the world are disarmed.

Some years ago I was at a meeting in Udupi, Karnataka, where Medha came to address the gathering. She spoke for three hours straight, after which she ate dinner with a few of us, and then got on the bus to her next destination. I remember thinking that this must have been how it felt to be in the presence of Gandhi. A soul in a voice, a mind in a tongue, no bones and no clothes between intention and articulation.

On screen before me now is the same Medha, satyagraha personified. I will not move. Empires have fallen in the face of such determination.How could it be safe for the Indian government to let Kak see this, to allow him to record it, to permit him to make available to millions of ordinary people a glimpse of their true moral strength that could resist, non-violently, all of the state’s brute force? No means no. This is what the censor is after.

Back at Sarai, lawyer Nandita Haksar is speaking, on another occasion, about her client S.A.R. Geelani, the Kashmiri college lecturer who was arrested under POTA on charges of conspiring to blow up the Parliament House in the December 13th attack, sentenced to death, and later released for lack of evidence.

Professor Geelani has come with Ms Haksar; he sits in the audience while she tells us of his harrowing experiences in jail, in the courts, in the media.

I am a couple of rows behind him, to his left. I can see part of his face, the back of his head. He seems very young, and extremely gentle. He blinks a lot behind his glasses. He is wearing a jacket, he listens intently to what is being said. What does he make of all this talk about war, about news, about television? The subject is him, or sometimes Iraq, Afghanistan, Kashmir. I am Lazarus come back from the dead. I try to reconstitute a vision of the room from Professor Geelani’s slow-blinking eyes. He must recall in his body the torture he was subjected to while in custody.

A few months ago he was preparing for the hangman’s noose. Now he sits listening to his lawyer, and to Shuddha, master of ceremonies, who spells out the evening’s theme, "Crisis / Media". I am Lazarus come back from the dead. I cannot recollect in that context, tense as I am from being in the presence of so much pain, what the character of Lazarus did, what death he died before returning to the world of the living. But in our country, there are laws to curb speech, and laws that can take away a man’s life. Take it away and never return it, for all that he may go free after some beatings, some burnings, some deprivations.

Censorship is not directed at the appropriateness of what we might say. Censorship is directed at the inappropriateness of what we notice, what we think, and what we remember, of injustice, of corruption, of cruelty. My friend Achal Prabhala, the writer, told me that he once had the opportunity to shake Nelson Mandela’s hand. From the way he described this brief encounter, it seemed to me that Achal had never expected to be so affected by the touch of another person.

This goes back to my intuition of what it might have been like to be in the presence of Gandhi. In our times, the greatest human beings are those who, when confronted with power in all of its nakedness, especially the overwhelming power of the state, say no, and mean it. Who resist the ubiquitous censor’s drive to take a hold of their mind and their moral sense, and against all odds, retain their humanity. Who look squarely at what’s before them, and then say it like they see it: I will not move. I will not be afraid. I will not go quietly into the night, but rage, and rage, against the dying of the light. When someone says this, s/he flares up, for an instant, against a horizon enveloped in darkness.

If there were enough such individuals, flaring up with the brightness of belief, ablaze with conviction, how could even the darkest, the most enveloping, the most totalitarian of political structures remain standing? The censor is a candle extinguisher. It snuffs out the smallest of questions, the tiniest of doubts, the slightest of observations, lest freedom spread like a forest fire. After what is happening in the Narmada Valley this Monsoon, perhaps we should liken the censor to the dam that rears its undemocratic walls until communities are drowned in the stifling waters of state repression and political unfreedom.The submergence of Tehri is frighteningly real and even more frighteningly metaphorical.

Historian Prithvidatta Chandrashobhi suggests that "freedom of expression" may not be an effective paradigm, not because freedom isn’t desirable, but because undue emphasis on freedom fails to take cognizance of the idea of responsibility. He would like "expression" to be replaced by "interaction". Why not think in terms of a conversation, rather than mere speech? Why not try to come up with a framework that would allow for a considered and considerate dialogue between different interlocutors, instead of defining the rules for a speaker as though s/he were going on in isolation, participating in a monologue?

The censor finds an opening in the public space of discourse precisely because there is too much conflict between isolated speakers, social actors expressing themselves without regard to or respect for one another. In place of this cacophony that is periodically shut down into dead silence through acts of censorship, Chandrashobhi calls for the conviviality of the conversational paradigm. Let’s not talk at one another, let’s talk to each other. This may indeed be an effective way to deprive the censor of its role in society - granting, for a moment, that it has any in the first place.

In Poona, following the vandalization of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute by Maratha chauvinists in January 2004, and the banning of American scholar James W. Laine’s recent book Shivaji: Hindu King in Islamic India (OUP 2003), historian Gajanan Madhav Mehendale swore off his on-going research. Reportedly, he disowned his own published volumes on Shivaji’s life and on the Maratha dynasties, and declared that he would abandon further work in this direction. What seems to have upset him particularly was the attempt, by the same Maratha vandals, to physically blacken the face of another esteemed Poona Indologist, Professor Bahulkar.

I have met and talked to G.M. Mehendale, sometime in 2001. I have seen his books and used them in my own research, since they are thoroughly useful compendia of all available sources on Shivaji and the Marathas, in which each fact of the Chattrapati’s life is presented after evaluating the entirety of available information. In my meeting with him, which took place at the home of Ninad Bedekar, Mehendale came across as a sensible and down-to-earth kind of scholar.

I asked him for his opinion about the work of another eminent Maharashtrian historian, Ramchandra Chintaman Dhere, who was, right around that time, slated to come out with a controversial new book in Marathi on the ancestry of Shivaji. His own idea of what counts as reliable historical evidence is quite different from that of Dhere, and for a third-party like me, both have their merits. Mehendale disagreed with his colleague, but didn’t express an outright condemnation, since Dhere is very senior and has a lifetime of history-writing behind him. Instead, the younger scholar reacted with a low-key sense of humor that allowed him to show respect for Dhere without agreeing with his historical method.

Against this background, when I heard of the emotional way in which Mehendale had allegedly reacted to the BORI incident, then, I was startled. From what I know of him - which is admittedly very little - but more from the quality and tenor of his history-writing, the violence of his reaction appears to be completely out of character. I would contend that when a historian wants to undo her / his own work, when s/he becomes self-destructive, as it were, it is time for a society to pay serious attention to the state of its civil liberties. A suicidal historian is surely a bad portent for Maharashtra, and for India.

What happened to Laine’s book, to Bahulkar’s face, and to the Bhandarkar Institute’s archives obviously drove Mehendale to despair for the possibility of continuing to read and write history in any reasonable fashion. How can we allow censorship to persist to the point that it frightens our scholars and intellectuals into abandoning their vocation? How can we accept it when thinking persons begin to self-censor, to shut down their own work before it is forcibly curtailed and their physical safety endangered? Should our greatest living artist, M.F. Husain, cease to paint because his works seem to invite more and more threatening gestures from different quarters? Should Salman Rushdie have given up fiction? Where will this intimidation of creative minds and impoverishment of public life end?

On 14 / 02, we ended the day by listening to Debjani Bhattacarya read out her translation of a new essay by Taslima Nasrin.

I do not read Bengali. I had heard from many friends whose critical judgment I respect, that the novelist is not a very admirable writer. But when I heard Taslima’s essay that evening, in her translator’s deeply felt rendition of it, I was moved.

I tried to follow the account that was being presented, of a tumultuous life, of a woman’s continuous battle with sexual violence, patriarchy, personal betrayal, trans-national exile, political interference, academic strong-arming, legal pressure, religious bullying; her confrontation with any number of individuals and institutions bent on abusing her body, curbing her opinions and breaking her spirit.

How can you be just about forty and the sky have fallen in around you like this; how can you be Taslima and still keep on, not just being, but being who you are? Whence comes the courage to combat the censor that will attempt ceaselessly to control what you think, who you love, how you live? How could anyone fault her for the lack of literary elegance; who cares about how accomplished a writer this woman is or isn’t, when the fact is that she is an extraordinarily accomplished human being?

Earlier this year, in January 2004, at the World Social Forum in Bombay, I had heard other such women, whose accomplishments cannot be measured except by reference to the stupendous force exerted by their governments and by states across the world to keep them silent - force that is wasted, evidently: Nawal al Saddawi, Egyptian human rights activist, Saher Saba, leader of the Afghan women’s resistance against the Taliban, Irene Khan, head of Amnesty International.

No, they said -- no to rape, no to custodial violence, no to cultural policing, no to forcible displacement, no to all the evils of the modern state and the excesses of patriarchal society. No means no. How could anyone not be moved? Is Taslima’s real role that she should be our standard of literary excellence, or that she should be our talisman of moral rectitude? Is it more important that she write novels competently, or that she remind us, by risking or even forfeiting her own freedom, of the value of our right to think, speak and act freely?

At the eye of the storm of censorship is the lone human voice, saying the same words to governments and gods, to men and machines, to the powers of heaven and earth: I will not move.

Let this be our mantra.

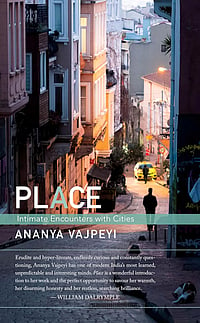

Rhodes Scholar Ananya Vajpeyi has a doctorate from the department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations at the University of Chicago. She is a Scholar of Peace 2004-05 with WISCOMP: Women in Security, Conflict Management and Peace, a non-profit think-tank based in New Delhi under the aegis of the Foundation for Universal Responsibility of His Holiness the Dalai Lama.