Periods can be painful and messy, and it’s a public health issue no one really talks about. According to a 2012 study, 96 per cent of the female workforce (it’s 91 for males) is employed in the informal sector, where staying home due to menstrual pain usually means losing a day’s wages or, worse, getting replaced. So it did seem like a step in the right direction when a Mumbai-based digital media company last year announced that all female employees can be on paid leave on the first day of their period every month. But ensuring that the first-day off is also extended to the overwhelming majority of women is more difficult than ensuring minimum wages are paid, which too isn’t often the case.

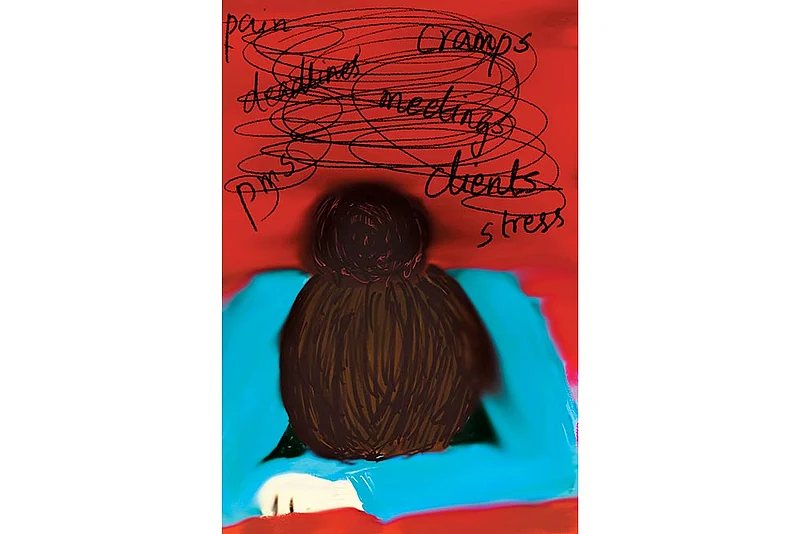

So does menstruation add to the odds stacked against women at work? Different women have different experiences with the menstrual cycle. While some breeze through their periods, many others face severe pain, heavy bleeding, headache, nausea, depression and sleeplessness. According to Dr Rishma Dhillon Pai, consultant gynaecologist at Jaslok Hospital and Research Centre, Mumbai, menstrual pain or dysmenorrhoea affects nearly half of the women in the working age group, and 20 per cent of them may suffer from endometriosis or fibroids that may cause severe pain and bleeding.

Then there are the differences related to the nature of work—for example, between work that involves standing long hours and that which can be done sitting. The way menstrual problems would affect a shop assistant’s workday would be different from the case of those working in call centres. The problems faced by those working outdoors would be different from those who work indoors. The menstrual cycle would affect someone whose job primarily involves physical labour differently from one whose work involves more mental engagement. “Overall, most women work through their menses,” says Dr Pai. “Education and information play a major role in dispelling myths, misconceptions and fears associated with menstruation. Most conditions are treatable and women do not need to suffer painful periods.”

One of those who haven’t experienced pain during their menstrual cycle is Dr Gayathri Vasudevan, co-founder and CEO of LabourNet Services India Pvt Ltd. Referring to her personal secretary, who is prone to menstrual cramps, Vasudevan says, “It became necessary for me as an employer and her immediate reporting manager to allow her to take leave during her monthly cycle. The management needs to be sensitive to women who suffer immensely during their monthly periods and allow them to work from home or grant them leave. But I’m not in favour of a policy that specifically grants leave to women during periods as I fear this will push back women to a time when they were isolated.”

“My periods have been debilitating, at times going on for 15 days with heavy bleeding,” says Kiran Manral, ideas editor with SheThePeople.TV, who was nine when she had her first period and was diagnosed with PCOS (polycystic ovarian syndrome) at 16. “But I don’t like to take a day off unless I am absolutely unable to function. That has rarely happened. But I also understand that a woman may feel she needs the day off to care for herself, and that’s completely fine. I think women should be given a few additional days of sick leave for this.”

Won’t more leaves accentuate the hiring bias against women, given maternity leave is sometimes informally cited as a reason to avoid hiring them in the reproductive age bracket? But even the idea of maternity leave had faced much resistance from employers, and is one of the gains of the struggles of women workers for their workplace rights. Women organised and agitated against the conditions that turned their capacity to be mothers into a disempowering factor for them vis-à-vis their employers—more cost-efficient as workers than men as they could be made to work more for less wages, with employers weighing their wages against the risk that they might have to be replaced on becoming mothers. As there were always others out of work and looking for a job, women mostly had to settle for lower wages and their average wage across sectors has been lower than men doing the same or comparable work.

Now that the concept of maternity leave has gained acceptance and has been written into labour laws in most parts of the world, including India (Maternity Benefit Act, 1961), doesn’t ‘period leave’, which too relates to a physiological process unique to women—and one encountered every month from puberty to menopause—deserve similar attention? Currently, menstrual leave is available to women in Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and some provinces in China.

In India, the directive principles of state policy enshrined in the Constitution contain provisions recommending that the State should enact laws for the welfare of woman workers. Article 42 says it is among the State’s goals to ensure just and humane conditions of work, including maternity relief. This means a law enacted in that light would be upheld as constitutionally valid.

“Menstrual problems must be addressed by passing a law entitling women to menstrual leave,” says Abha Singh, former civil servant and an advocate practising in the Bombay High Court. “All eyes must now turn to Parliament, which, having enacted the Maternity Benefit Act in 1961, is at an opportune moment to undo the injustice that has plagued women for ages.”

With rising social awareness about the hardships women face in the workplace, there is a gradual realisation that menstrual problems cannot be brushed under the carpet. Just like a few companies are now offering free egg-freezing options to their women employees, some may also offer menstrual leave as a way of showing concern for their welfare. Obviously, not every company would agree on this. “It’s simply not feasible to have an employee missing from work each month, for something like a period that can be managed,” says Richa Singh, CEO of Niine Sanitary Napkins. “Everybody at some stage suffers from allergies, headaches or gastric issues, and we can manage these and maintain our work schedules. There should be no stigma attached to openly talking about it, and a woman should be able to take a sick leave if she is having a particularly tough period.”

Dr Veena Aurangabadwala, a gynaecologist at Zen Multispeciality Hospital, Mumbai, says, “Instead of asking for period leave, women should focus on improving their pain endurance and fitness, by having certain minimum hours of physical exercise every week.” Many women manage their periods with pain relievers, warm baths or hot fomentation. If the discomfort is so much that it stops a woman from working, then she must be evaluated by a gynaecologist to rule out any pathological cause such as endometriosis or fibroids.

Employers too can explore options other than granting period leave. “They can increase the number of casual or sick leaves for their female workforce. They can leverage technology wherever possible to offer telecommuting and work-from-home options,” says Rituparna Chakraborty, president of the Indian Staffing Federation.