Eudora Welty, whose writings were defined by a sense of place, once said, “Geography is fate.” Last week at the Eudora Welty lecture at the National Cathedral in Washington DC, Salman Rushdie told us of his father learning with dismay that he was going to be a writer. A piteous cry, almost involuntary, came out of his father’s throat. “What,” he cried, “will I tell my friends?”

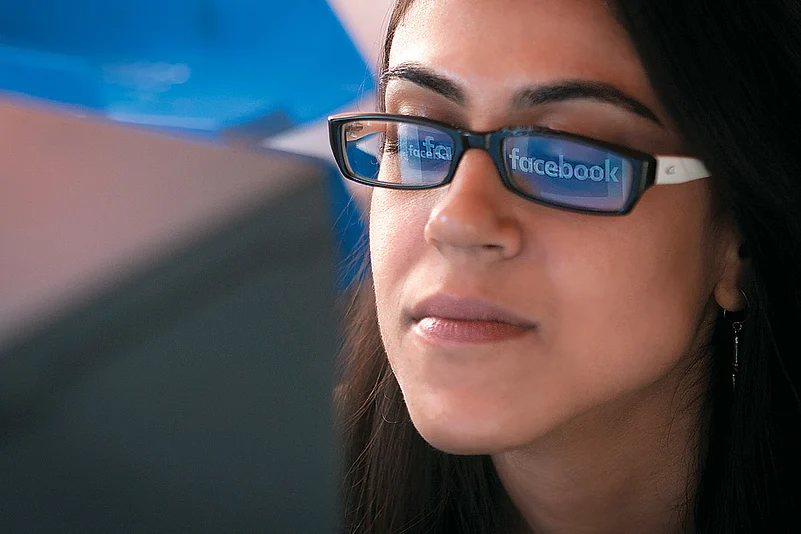

Facebook, launched in 2004, recognised this truth about the centrality of friendships. It gave the world snapshots of lives at six degrees of separation unfolding 24x7—a mountain climbed, a toilet leak fixed, a daughter married off. Teenagers bought into it at once, the rest followed. Its overlapping Venn diagrams of networks transcended time zones, and geography was no longer fate. Between a sweet birthday cake and a bitter divorce, we got a perfect haiku and a grainy TBT (throwback Thursday) picture of better times.

A dozen years later, we have almost two billion Facebook MAUs (monthly active users)—more than WhatsApp (500 million) and Twitter (284 million) and Instagram (200 million) combined. So much for its doomsday predictions every few years. And contrary to rumours of millennials fleeing this space after baby boomers stumbled upon it, the most common age demographic is still 25 to 34. Smartphones have helped enormously. Half of the younger users go straight to Facebook upon waking up, and almost half of marketers report that Facebook is vital to their business. Work or play, there’s no dodging its grasp. Facebook Messenger, at 900+ million users, has caught up with WhatsApp (also a messaging app, now owned by Facebook) and has a host of new features, and its web articles load an ample 10 times faster than elsewhere. Facebook, along with the expanding Facebook Messenger, is all set to be the one-stop shop catering to every possible need an internet user has, thus freeing up time for the real stuff. It has changed how we consume news, with the blessings of not only big names like the New York Times (among the first to capitalise on the value of shared links), but also small non-mainstream sites that function only within Facebook and attract a whopping number of eyeballs.

To all of which we can only say “aiyo yo”, officially an English dictionary word as of this month.

It’s funny when I remember how some of my friends saw Facebook as the gateway drug to dangerous groupthink, a massive online con job, a Zuckerberg money machine, a scam for targeted ads and a ticking identity-theft timebomb. Yes, it does have 83 million fake profiles and, yes, it can potentially be a schmoozing site for shallow agendas or needy narcissism. But used creatively, it can also be a thing of wonder and beauty. Attention-seekers and vaguebookers may crash and burn, but empathy has no expiry date.

This week, a Calcutta-based MTech student’s clever Facebook post criticising undue government expenditure on Durga Puja immersion carnivals, and the West Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee’s plan of a 10-day Durga Puja from next year, was magnified into a huge hoarding outside her house, where a gang of protesters collected and ordered her to apologise. She refused. The hoarding had to be taken down after media attention, but she was too upset to complain to the police. A few years ago, the same Trinamool Congress government had arrested a professor for posting a rather funny cartoon on a minister’s dismissal. This was one of several arrests in the country over Facebook posts. In less free countries, social media has tried to support uprisings, with mixed success.

Off-wall Closed Groups are the soul of Facebook—they offer hangouts for common interests with like-minded people, away from prying eyes, and often create deep, lasting friendships. There are hobby horses and retro photos, stockpiles of fascinating trivia, support groups with advice for every affliction or app. Being invisible to your own Timeline while sharing stimulating debates and inside jokes with nerdy, creative types can be extremely liberating. Facebook Closed Groups are not entirely anonymous like other sites. But they carry the confessional side of Tumblr, with greater depth; borrow the problem-solving of early chatrooms within a safe space; create time-sucks like Twitter, but without its intimidating trolls.

A wall is anything you make of it—cute kitten videos to political catfights. It can enrich or distract. Each like, share or comment shapes your feed and narrows it down to exaggerate bias, or highlight that one off-shoulder purchase or song choice for target ads, to the exclusion of other opinions or brands. If you’re not careful, you’ll end up with an echo chamber of more extreme versions of your views and buying/reading history in your news feed—broader, free-ranging posts will be crowded out. Sadly, that’s how algorithm rankings work. It’s complicated. Don’t worry, KJo, Uri and a former 007 refusing to chew tobacco will still be high on your feed.

Mark Zuckerberg at a developers’ conference in San Francisco

You can discuss cough remedies, compost pits or cartography, leverage Facebook solely for business contacts, hawk passion projects, shamelessly direct friends to emotionally blackmailing chain posts and gofundme pages. If faking bonhomie or manufactured outrage is important to your process, that works too.

Your clueless great-aunt shares anything—“breaking news” from three years ago, annoying inspirational quotes, and clickbait. She posts non sequitur comments on your public convos and tags you on awkward family photos. You love her anyway.

A gentle slacktivist comments on a belligerent know-it-all’s thread, but then posts smileys at the end so as not to upset his feelings. There are ex-boyfriends to stalk, comments to judiciously sprinkle, rude retweets to get huffy over and cross-post.

A name-dropping, party-hopping, vaping grad makes her friends wallow in FOMO (fear of missing out). One of them takes huge satisfaction in not telling her that her no-privacy settings have made it easy for any future employer to google her.

A pansexual doula midwife looks at a dating marathoner’s badly-angled cover picture, hoping she breaks up, because she has a thing for her. Maybe paradoxically, she also hopes she will soon be pregnant, and will employ her for a delicate water birth. A stranger sends a creepy message to her—it lands on her Other folder where she will never see it.

A schoolgirl uploads an instagram on her Wall—three hours pass and there is not a single “like”—she is finished! Everyone hates her! A meme is worth a thousand status updates. It is also totes easier to share. She will only do memes now. Posts are so lame anyway.

Not every Facebook friend is worth the upkeep. I use the sliding scale of “mute”, “unfriend” or “block” for the Nasty Women and Bad Hombres out there. There’s the friend who imposed his wingnut views rudely and repeatedly on my wall. And the other one who took every sexual assault news story (Steubenville onwards) as a call to proselytise men’s rights. Both were called out on their lack of courtesy and logic. One unfriended me. I muted the other. Politics, religion and gender are sticking points on Facebook, as in life. What’s the beef? Taking the middle path is rare. Medium, rare.

I discover that people have multiple identities. Shy stutterers reveal sparkplug online personas, full of repartees. Friendly, educated coworkers turn out to be anti-Semitic climate-change deniers on their walls. A feel-the-Bern liberal poet can be an anti-vaxxer and borderline conspiracy theorist.

Facebook is not always a shiny happy place to be. Casual chats bring out smells and sounds easy enough to place but tough to reach, and heartlessly redefine for me my idea of home. A disturbingly large number of online Facebook memorial pages remind me of people I’ve known mostly offline—some young, some vibrant, all sorely missed.

Confession: I took a Facebook daily-fix break before writing this article on Facebook. How very meta of me. Now please share this post, for the health of this magazine and the future of your soul.

Meanwhile, it’s a weekend here, there’s advice on statins (good/bad?) or grad schools (here/there?) to crowdsource, messages to reply to online, offline meet-ups of online literary groups to save in my calendar, the old instagrammed Chandni Chowk sheermal and nihari to nostalgically upload to Facebook. If only I was there. Wait. Beef isn’t allowed, it’s 2016. Nobody can eat it back home now. I begin to feel better about my ubiquitous steak for some reason. I like mine medium rare.

(Nandini Lal is a columnist based in Washington DC.)