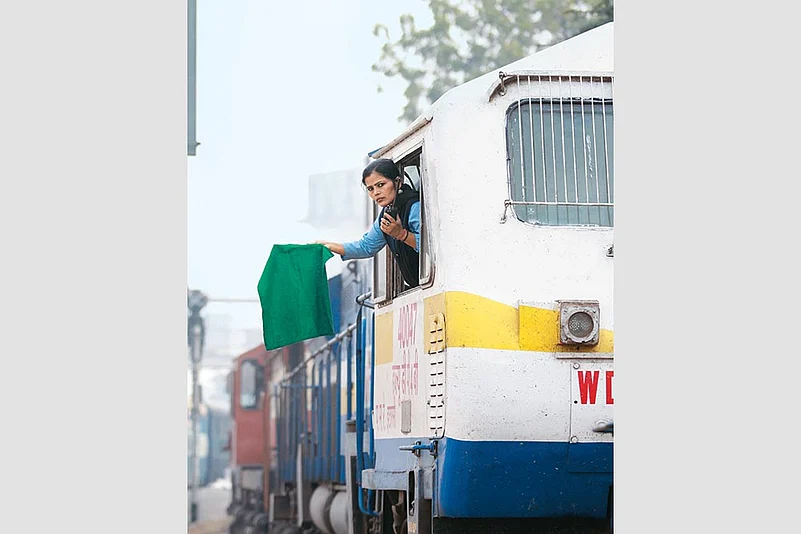

A locomotive pulling more than fifty freight coaches rattles through the countryside, its headlight piercing the moonless darkness, the horn occasionally blaring to alert wildlife and humans alike. It’s a chilly night; almost ghostly with the ululating owls and bats doing their back-and-forth, up-and-down loops. The train fords jungles, fields, hamlets, rivers and streams noisily—the clackety-clack brutal on bridges. And behind the wheels, or rather the levers on the loco’s console, the driver sits tight, looks straight and immediate pressing matters runs through her mind.

Her? Yes, she is a she—one of the over 500 woman train drivers with the Indian Railways. Yes, she is among a handful to challenge stereotypes and social prejudices that a woman’s place is at home, and trigger a change among people who harbour a general disapproval of working women. But first, she had to overcome her own doubts and fears of running a train. She had to get comfortable working night shifts and working in positions traditionally held by men, carrying out tasks many in this conservative society have only seen men do before.

The train presses full steam ahead and the driver gets impatient. She needs to use the washroom and change her sanitary pad. The driver’s cabin is a tight squeeze; doesn’t have a toilet. The next station is 50km away. Can she make an unscheduled stop? That won’t reflect agreeably on the log book. She prays for a forced halt—the stops goods trains often make to let a passenger express pass. She can get down and complete her ablution by the tracks. But won’t her co-driver, a man, notice? He won’t. It is pitch-black outside. The thought brings some comfort, flittingly.

Coaches of passenger trains have toilets but drivers cannot access them. Freight trains have none at all. The absence of a loo is among a range of occupational hazards woman drivers face every day. And they have, or had, adopted harsh measures to circumvent the hurdles—sort of self-flagellation in some cases. Samta Kumari, a goods train driver, avoided drinking water for 10 to 14 hours while on duty after she joined the railways as an assistant loco pilot in Lucknow in 2010. “Gradually, I opened up with male co-drivers. I have no option but to relieve along the tracks and away from the view of the male co-driver during night shifts. Getting off in rural areas at night is very unsafe,” says the 30-year-old.

The problem exacerbates when a driver is menstruating. “During periods, we don’t get time and place to change sanitary pads. How can a girl from a conservative family ask a male colleague to vacate the engine for her to change the pad?” said a female assistant pilot from the Allahabad division, wishing not to be identified.

Sure, the working conditions of all train drivers— man or woman—are harsh. Recruits start as assistant pilots, a role that requires them to investigate problems and emergency “chain-pulling” halts. This involves getting down in pitch darkness and inspecting different coaches. Duty hours of freight drivers can stretch from 18 to 36 hours. “Freight trains have no timings. Sometimes they are halted in deserted areas, dense forests, for five to ten hours. Even a male driver can’t think of getting out of the engine,” says Sanjay Pandhi, working president of Indian Railways Loco Running Men Organisation.

The conditions are keeping many woman drivers grounded. Responses from 60 of the 67 railway divisions across the country on a right to information application suggest that not more than 20 per cent are deployed gainfully to do their primary job. Railway officials say a woman driver should log around 70,000km each year, but the RTI reply suggests they do much less. For instance, in Raipur division, there are three woman drivers and the senior-most has logged 11,0556km driving goods trains in the past 13 years. That’s an annual average of 8,500km. In some cases, the average is less than 500km. Most divisions don’t put women on night duty and give them short-distance trains. Some drivers were shunted to desk jobs. And the alibi, officials say “we have to engage them somewhere. They are voluntarily asked to do stationary job in other departments such as crew controlling unit, stationary division, etc.” Drivers’ association chief Pandhi is unhappy with this arrangement. “They are not officially transferred to other departments but are asked to do that voluntarily. So who will fill the gap?” Pandhi asks, underscoring that the male colleagues have been asked to soak the additional burden.

A woman driver faults senior officials for the indifference. “Seniors don’t want to encourage women to drive trains because they know if they do, they will have to create amenities and take responsibility.” Another employee, an engineer, alleges that the officials are not supportive since “they feel that if something happens, it might land them in trouble”.

Another big challenge is social conditioning. “Since women are not conditioned to believe they can or should perform a job that keeps them on the move, they often prefer sedentary duties,” said Arundhathi, a Tata Institute of Social Sciences scholar working on a pan-India research project on woman train drivers. It also works the other way round as many drivers don’t support their female colleagues. There have been cases of sexual harassment too; not surprising in a country rife with sex crime. Last year, two male drivers allegedly molested an assistant on board a train in Jhansi. The case is being investigated.

Surekha Yadav, one of India’s first woman train drivers in 1989, feels lucky to have started her career in Mumbai. “Though I did face a hostile environment in a completely male-dominated industry, it was better than the current environment in the northern states such as UP and Bihar,” the 53-year-old says.

The railways has taken initiatives to bring facilities for woman train drivers, a praiseworthy effort, though those in the field feel a lot needs to be done. “Implementation of women-centric policies is the biggest challenge. Even other woman employees such as guards and ticket collectors find a tough time on the job because of dismal facilities,” says Padhi. Some train engines have bio-toilets now, and there are ladies-only accommodation and washrooms at several stations. Many stations have sanitary pad vending machines; some stations are managed entirely by an all-women crew such as Jaipur’s Gandhinagar. “The process is on but it will take time to have bio-toilets in all engines. We are concerned about the troubles woman train drivers face and we are trying to solve them one by one,” says a senior official of India’s national transporter that has 1.3 million employees on its rolls, among them over 1,00,000 women.

For Madhuri Manish Urade, she got what she dreamt of as a schoolgirl to do something different and challenging when she became an assistant driver in 1993. “No doubt, this is one of the toughest jobs but I enjoy it. When I started, there was no separate toilet for us. Facilities are available in some of the stations now. The railways is making efforts,” says the freight train driver with the Nagpur division.

Driving a train doesn’t require muscle any longer; the days of shovelling coal on steam trains are dead. With lipstick in place, eyes darkened with kohl, black dupatta adjusted over her blue churidar, and phone at the ready, the plucky Kumari does what was a male preserve not so long ago. She is punctual and professional too. She has overcome the gender stereotypes, but there are obstacles that bewilder and upset her—the old wives’ tales of seduction in the driver’s cabin. “The wives of male drivers harassed and threatened me on many occasions for accompanying their husbands on long journeys,” Kumari says. The spunky woman took the problem head-on, instead of suffering in misery. “In 2013, I filed an FIR to give them a befitting reply.”

.png?w=200&auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max)