The quest for the elixir of life began the time man walked the earth. Though the magical potion is still elusive, the abundant tips on the internet and good medical care have been a ready substitute and probably have had some effects on longevity in urban India, while fresh air and simple living continue to be the basis in rural areas. Certain religious texts put the span of human years as 70 and, if one is strong, then 80. Some communities mark 84 years with special prayers for the one who has witnessed a thousand full moons. That seems to be a threshold age that many struggle to cross.

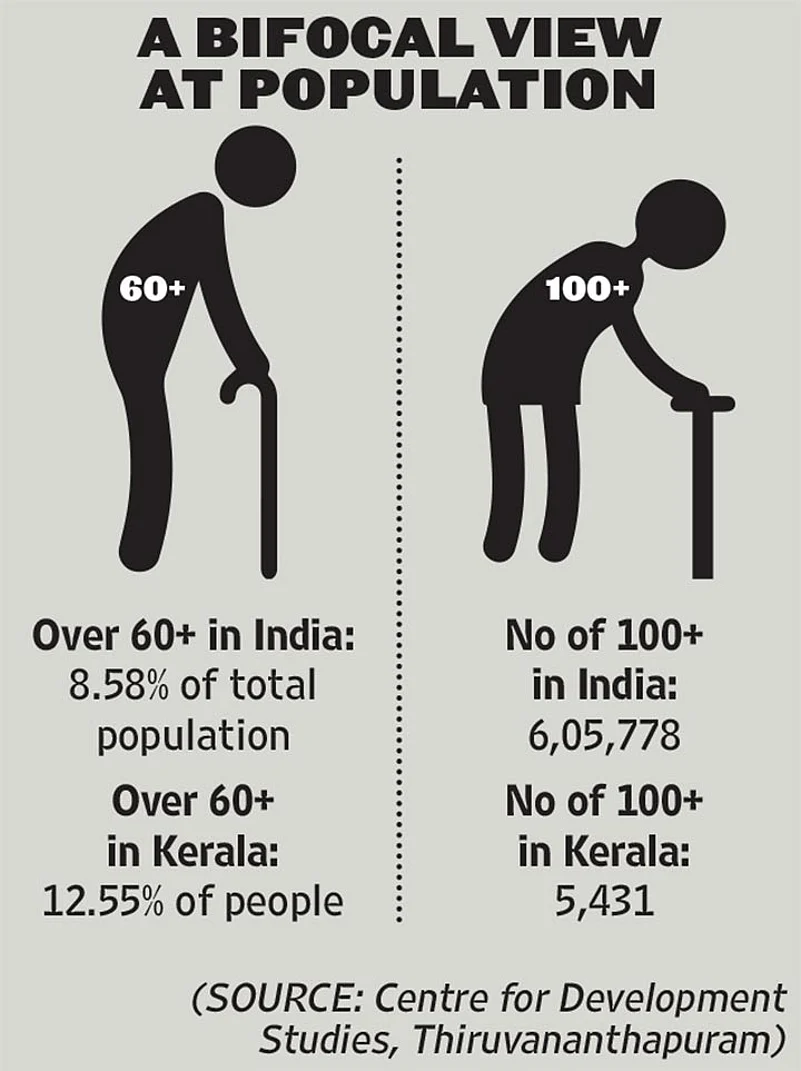

But not in Kerala, which has India’s highest life expectancy among the elderly, percentage-wise. Keralites are ageing and, ageing well into their nineties and sprinting past the 100-year milestone with considerable ease. The 2011 census says that no less than 75,151 people in God’s Own Country are in their nineties, while 5,431 people have crossed the magical figure of 100. S. Irduaya Rajan, an expert on the Kerala demography, is cautious about the absolute numbers. “The number of 100-plus people may be exaggerated. Many of them don’t have proof of their age and most people have an inclination to round off their age,” says the scholar at Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram. “They may be still in their nineties.”

A few of Kerala’s public figures are celebrated nonagenarians. Former chief minister V.S. Achuthanandan is 93, courtesy a disciplined lifestyle, while his one-time Communist party colleague, ex-minister K.R. Gouriamma, is four years older. Both hail from coastal Alappuzha district and retain remarkable memory. Some among the more ordinary people have surpassed the politicians’ indefatigability, and added another decade to the magical 100. In 2015, the oldest woman in Kerala, Rosa, died at the age of 112 in Thrissur.

Interestingly, Wikipedia lists those who have crossed 110 from various parts of the world, but that doesn’t feature Padmanabha Marar. Residing near Palai in south-central Kerala, Marar is well into his 112th year, according to his children, though does not have anything to prove his age. The academic records remain untraced after the Government LP school where he studied till class four was reduced to rubble long ago.

Musician-drummer Ramapuram Padmanabha Marar at his home

At his home in verdant Ramapuram, the frail Marar chants Ramanarayana, and lets on the big secret for his long and contented life: “I’ve never got angry with anyone. I have always been friendly with people. If people didn’t have enough to eat, I fed them.” His son, Gopalakrishnan P.M., says it has been only in the last few months Marar stopped playing the edakka because he is too fragile to stand and sing, playing the hourglass drum without support.

Marar has been singing and playing the instrument at the neighbourhood Sree Ramaswamy temple since he was eight. “I was employed there. Back then, the temple had a lot of paddy fields leased out. I would go to collect the rent. The temple used to pay me in kind: 2-3 kilos of cooked rice a day. That was sufficient for us. Anyone without food would come here and eat with us,” he trails off. “I then took on the job of blowing the conch at the shrine and then play the edakka during the morning and evening pujas. Every day, we used to get payasam in the temple. I loved the pudding. I have always been a vegetarian and these days I enjoy just rice and buttermilk curry.”

From when he was eight till the age of 105, Marar went twice or thrice a year to Sabarimala. In younger days, he would tie the bundles for fellow pilgrims to the hill-shrine. “Those days, we could hear the roar of the tiger as we trudged through the forest. It’s another matter we feared the wild boar the most.”

Another Kerala centenarian lives in the state capital. K. Ayyappan Pillai, 103, shares the secret of long life simply as “malice towards none and goodwill to all”. An advocate and a politician, Pillai had met Mahatma Gandhi in 1934, when he was 20 and was to lead the freedom struggle icon on to the dais. “It was on January 28. Gandhiji asked me what I was doing and I told I was doing my degree and planned to take up a government job that was promised to me. (My father was a senior officer in Divan Muhammad Habibullah’s office.) Gandhiji told me not to go for a job, but to do social service.”

Pillai says his father was sorely disappointed when he declined a government job after graduation; instead turned to law. He joined the Travancore State Congress in 1938—before he enrolled at the Bar. In 1942, when the Trivandrum Corporation was formed, Pillai stood for councillors’ election and won. What he holds most dear is the negotiator’s role he played between the Maharaja Chithira Thirunal Balarama Varma of Travancore and the State Congress to sign the instrument of accession.

“The divan, C.P. Ramaswamy Iyer, had wanted Travancore to remain independent. The people were angry with him and when he attended a function he was attacked. The State Congress leaders like Pattom Thanu Pillai and others were thrown into jail,” Pillai recalls. “The king asked me to go and meet them. The leaders said he should sign the instrument of accession and I conveyed it to the Maharaja.” Like Marar, Pillai too rises early at 4 am and works through the day. Even today, he does not sleep in the afternoons and sleeps only at 11 pm. His only sadness is that the cleanliness of the city has come down terribly.

On the banks of the Maramon river in semi-hilly Pathanamthitta district lives Rev Dr Philipose Mar Chrysostom. The 100-year-old bishop of the Mar Thoma Syrian church is just back in the chair after blessing a bakery and housing contractor’s workshop. “I am up at 5 am, earlier I used to rise at 4. I am ready by 7 to meet a stream of visitors,” he reveals.

Chrysostom, whose life is entwined with the growth of the Mar Thoma Church, is known for inter-religious dialogue and sense of humour. “I began my relationship with God from when I was in my mother’s womb. I used to love school but I was not too fond of studying. I was an average student,” he says. Chrysostom narrates a funny incident from those days when the classroom had only benches and no desks. “We used to stick our buttocks out and put our book on our laps to study. I once got my maths problems wrong and the teacher who was passing by beat me on my buttocks and asked me to write it again. I got it correct the next round as if by reflex.”

The Mar Thoma church, which had broken away from the parent Jacobite Church, was poor then. “In the church, people sat on the floor. There was simplicity and compassion for the poor.” Today, the bishop feels spirituality has taken a back seat with the church having grown amid increasing finances. “It’s not just the people, even the priests love comfort,” he adds.

So, what is the recipe for such a long life? “Well, secrets should never be divulged,” the bishop laughs.

Up the state, 40 kilometres north of Kozhikode, Chemanchery Kunhiraman Nair had celebrated his 100th birthday two monsoons ago. Living in his quiet Malabar village near Koyilandy, diminutive Nair continues to occasionally perform the art he likes most: Kathakali. If it was as Krishna that the actor-dancer debuted and gained fame in his more active days on the stage, the mischievous mythological character continues to be the favourite role for the bespectacled centurion who runs a cultural school in Cheliya since 1983.

“I am a thorough believer of god,” the artiste says, also noting that Gandhian ideas have had a role in his mild manners. Pacifism, he knew as a youth himself, was essential to existence. For, a tragedy hit Nair at 38 when he lost his wife after six years of marriage during which she delivered a child who didn’t live for long. He never remarried, instead focused more on the arts that were anyway his passion since childhood.

Nair, with no health problems whatsoever, isn’t known just as a Kathakali artiste. He has had trysts with other dance forms, including a couple of experimental forms that found stages across his state in the last century. “But these aren’t exactly what makes him a great,” notes Kathakali buff Prasanth Gopalan of nearby Vadakara. “You seldom find people with such a clean heart. Ashaan (master) brims with innocence that even children don’t have today. And his bhakti for the arts…imagine somebody starting a Kathakali institute channelling the entire money from partitioned family property!” he notes about Nair, a winner of Kerala Sangeetha Nataka Akademi award and fellowship.

Recently, in early June, at the 80th birthday celebrations of Kathakali maestro Kalamandalam Gopi, Nair shook a leg at a forenoon get-together, much to the fun of the crowd at Thrissur.

Amid all the sad tales Kerala generates about its geriatric crowd left unattended by younger members of the family who migrate to other places of the country or abroad for livelihood, the state manages to announce celebration of old age as well. The centenarians are a validation of what 19th-century English poet Edward Fitzgerald says: It’s for the last of life for which the first was made, for youth shows but half. The best is yet to be.

By Minu Ittiype in Kochi