Outside the gates of a residential society in New Delhi, in the shadows of the trees, Bhavna Paliwal quietly steps out of her SUV. She is in disguise, dressed like a domestic help in a cheap orange polyester salwar-kameez, chappals from the local market, plastic bangles and chipped nail paint. Her story is that she has been spurned by her lover and is in desperate need of any work she can lay her hands on. There follows a week of gossiping and complaining with the other maids, including one in particular who is working in the house of the suspect, and Paliwal has all the information she needs. Case: pre-matrimonial investigation. Period of investigation: three weeks. Result: not suited, the groom is having an affair with the maid.

The 40-year-old Paliwal is India’s very own Precious Ramotswe in the flesh. Plump and jolly, she is a master of discreet disguises, with a gamut of investigative skills to her credit. She can tell you if your partner is cheating on you, help you fight wrongful alimony or battle false criminal charges. She can detect frauds in your firm and sniff out corruption, to list a few items in her repertoire. She is one of a growing number of women who live the thrilling life of private detectives, veiled by the garb of ordinariness.

But no, she is nothing like Miss Fisher of the hit Australian detective series Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries. She is not wrapped in designer trench coats, a hat covering half her face, sporting dark shades and red lips as she chases murderers and marauders with one hand on her Colt. Most of the time, hers is a tedious job that consists of going through reams of call record statements and credit card bills, or reading copious numbers of emails. But some cases do require action beyond the computer, and women like Paliwal are in high demand.

“Women are excelling in the field because of their ability to blend in, and make people comfortable to open up to them,” says Shaumi Sharma, investigating officer, Kapsi Detective Agency. Honey trapping is a key advantage women have, being able to use their ‘charms’ on men and women alike. In 2006, Sharma had taken up a documenting job at a detective agency after college, when she was handed an investigative assignment that needed a “woman’s touch”. She still came to work in knee-length suits and short heels; what had changed was her location. Now she was in the field, her camera tucked away, following the suspect, waiting for endless hours in his office complex, and trying to get into his inner circle.. “Patience is the key,” she says. She has never looked back since.

Indeed, many of these women stumbled upon the profession. Ketaki Dutt Paul was a detective and crime fiction writer whose stories were published in Detective Digest. Her publisher, who also ran a detective agency, offered her a job as an investigator. Nidhi Jain, director, Sleuths India Investigations, holds an MBA in finance and was an investment banker before deciding to become a private detective. “Growing up on Byomkesh Bakshi, I was fascinated by the world of investigation, and when I was introduced to it by Naman Jain, a promoter at Sleuths, I decided to join him part-time,” says Jain. This became full-time soon afterwards.

Nidhi Jain

Jain is particularly proud of her success in a recent insurance scam case. A Delhi group was befriending elderly people and selling them fake insurance policies with a promise of a 300, or even 500 per cent bonus within a year. Jain took up one such couple’s case. It took a month of staying with the couple as their daughter, luring the suspects to come back for more cash, and working with undercover police, before nabbing an accomplice, who led them to the main suspect. The woman, who was convicted, would take the cheque from the victims, and sell an actual policy to another couple for cash..

"It is a combination of working for yourself, good earnings, and also being able to help others around you,” says Paliwal. Recently, she tracked the activities of a schoolboy at the request of his parents, who had noticed a change in his behaviour. Within a week of simply following the boy on his way to and from school, it was found out that he was taking drugs—rat kill cubes—with aerated drinks. And it hardly ever required hiding behind bushes, trees, or buildings as the movies often show. The key is to blend in with the environment and think on your feet, in order to change roles seamlessly. You must be ready, at the drop of a hat, to become someone who is looking for directions, chit-chatting, or casually strolling in the neighbourhood. The fee for a preliminary investigation can be as much as Rs 10,000 per day. “It can go up substantially based on the risk involved and the equipment needed,” says Sharma. The danger of backlash from the suspects often looms over detectives.

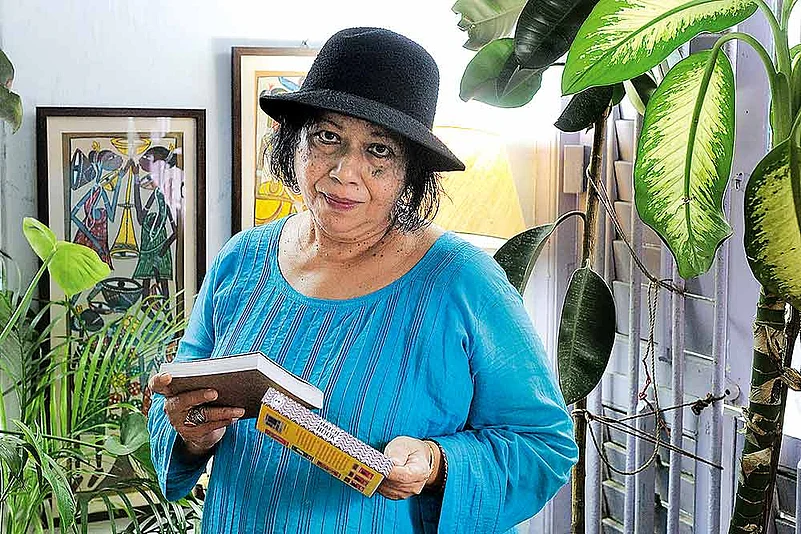

Bhavna Paliwal

It’s never easy on the home front. The women’s families worry about what people will say about their daughter’s profession. “Coming from a conservative family and quitting a stable profession of banking did mean a lot of resistance from my parents,” says Jain. Today, she is happily married, and even has relatives coming to her for pre-matrimonial advice and enquiry. “Yet, there is perceivable risk in the profession, and a vulnerability to exposure which the detectives account for by going out of their way to be ordinary,” says Anandana Kapur, director of Jasoosni, a documentary on the lives of women private detectives in India. Much of the time, men and women detectives are assigned to a case together.

Of course, technology has aided the investigations to a great extent. “I remember a time when investigation meant long physical enquires, discreetly following people, and keeping tabs without the help of technology,” says Paul. Many remember using bigger digicams that were easily detectable, but today there are high-definition spy cameras that can be concealed practically anywhere—your diary, a cup, bangles, earrings, pens, glass cases—and gadgets like sunglasses that allow you to see what’s happening behind you. “And these things are easily available in Palika Bazaar,” laughs Sharma. Then there are higher-end gadgets, such as the night vision glasses which come from abroad and require a great deal of investment. Her company has also invested in a forensic lab where they have the equipment to recover any kind of data—encrypted, deleted, or destroyed.

Even with everything in place, a case need not necessarily come to a satisfactory conclusion. Paul remembers investigating the case of a boy who went missing in Mumbai. Outpacing the police, they had already traced the abduction to Uttar Pradesh—but to no avail, as nothing could be found afterwards. “The one thing that goes unshielded is the impact that these cases can have,” says Paul. After a few years, she was discouraged by the seamy side of life and went back to being a writer of detective fiction. Some conjecture that this hardened view of life may be the reason that there are fewer women than men in the industry. “And bad timings!” says Jain, who has little time to herself, given the late night and out-of-station investigations that she must undertake. The work is certainly not for the faint of heart, but if you have the talent for it, there’s enough money to be made, and it’s certainly more exciting than the average nine-to-five job.