Alpha, omega, tau, proclaim the signs on the highway. Beyond the Greater Noida sectors named after Greek alphabets, a dirt underpass branches off from the spanking Eastern Peripheral Expressway to the dusty village of Bisaich. It is located on the fringes of the National Capital Region, but is a world apart from the neighbouring upscale sectors.

However, Bisaich, which gets power supply for only half the day, has something in common with Japan and Scandinavia—many of its residents are old or getting there. In the courtyard of a house close to the Baba Mohan Ram temple, eight men between 50 and 70 sit around a hookah, immersed in animated conversations. When asked about the elderly population, they estimate that three out of 10 people in the village are above the age of 60.

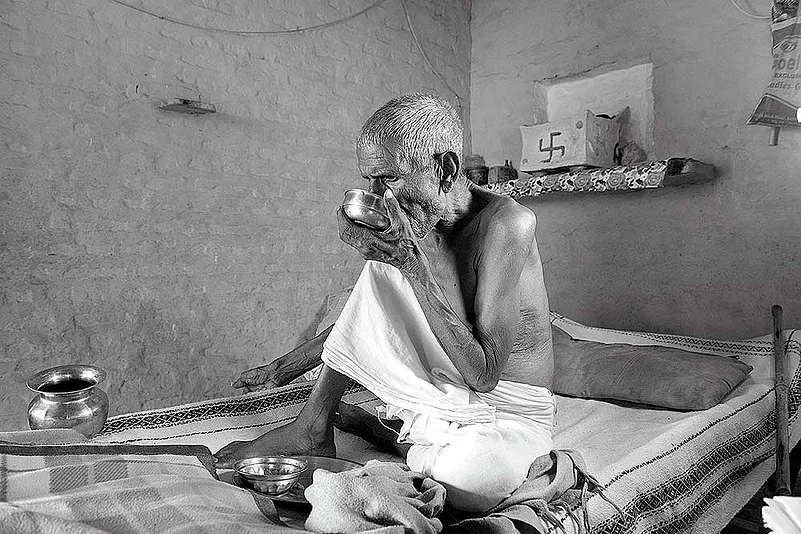

Sadi Ram, a 74-year-old farmer who has lived here since he was born, is reclining on a khaat. He is a proud father of six children—five boys and a girl—all of whom are married and don’t stay with him any longer. “If they don’t work, how will they fend for themselves and feed us,” he says. Two of his sons have set up a car-repair shop in Delhi and send Rs 8,000 every month for his expenses. Three to four bighas of land isn’t enough to feed him and his wife, who was in Noida at that time with her daugher-in-law. Sadi Ram didn’t go there—he can’t move like he used to because of a spinal condition.

Desh Raj, 70, never married. His nephews tend to him..

Four houses down the alley, 70-year-old Desh Raj sits on a charpoy. His house is not cemented and there is not even a ceiling fan in the room despite the temperature edging to the mid-40s outside. Smoke from a hookah suffuses the air. He doesn’t respond much to questions, but breaks into a chuckle when asked if he puffs on the hookah regularly. A farmer all his life, he grew jowar and wheat, but is unable to anymore. “Inko is taraf lakwa maar gaya hai (He’s paralysed on this side),” his nephew says, pointing to his uncle’s right. Desh Raj is a bit of an outlier for his time—he didn’t get married. His brother’s children now look after him.

Bisaich presents a microcosm of what is happening across the country—although more than 50 per cent of Indians are below the age of 25, the population of baby boomers is significant. Children are migrating to richer pastures while parents fend for themselves or rely on money sent by their kids. Healthcare is expensive and awareness about problems that creep up in old age low. An RBI report from August 2017 says that in 2016, a mere 23 per cent of the population was saving or planning for retirement.

It is a problem which will only get worse as life expectancy continues to increase. According to the National Policy on Senior Citizens 2011, the demographic trends indicate that between 2000 and 2050, the overall population of India will grow by 55 per cent whereas the population of those above 60 will increase by 326 per cent. The number of 80+ will swell by 700 per cent, making them the fastest-growing group. According to census data, 10.7 crore people were above the age of 60 in 2011, that is, 8.6 per cent of the population. This figure will rise to 21.1 per cent in 2050.

The social dynamics in Bisaich reveal another aspect of this issue. When a woman in her fifties tried to interrupt the hookah fix, the men told her to buzz off. This is self-entitled patriarchy. In this society, women have less resources and support to deal with the problems of old age. Those who married older men have it worse. Government data reveals that widows outdo widowers by a ratio of 3:1. “Women, especially widows, have no social and financial security,” says Aabha Chaudhary, founder of Anugraha, an NGO which runs three elderly daycare centres in the country. “About 80 per cent of the aged live in villages and about 70 per cent have not been educated. Those who live in far-flung areas have less access to healthcare.”

“Women live longer and have different health issues,” says Sailesh Mishra, founder of Silver Innings Group, which has several offerings for senior citizens. “When a man makes a will, he often divides it amongst his children but forgets his wife. Women sometimes don’t possess basic skills like how to withdraw money. They need joint accounts and property rights. ”

Under the Integrated Programme for Older Persons (IPOP), the government provides aid to over 400 old-age homes. However, Subash C., the general secretary of Indian Red Cross Society’s geriatric home in Faridkot, Punjab, isn’t enthused. He says that people can’t afford privately-run old-age homes. Others aren’t able to maintain standards or manage the bare minimum. “Jeena hai toh jee rahe hain (The people are somehow surviving),” he remarks, referring to the elderly there.

His facility hosts about 20-30 people at a time, three-fourths of whom are women and need female attendants. “We haven’t been getting funds for the past five-six years (from the government). When we began 20-25 years ago, it was regular. Then it got late and stopped altogether. We have applied again this year. For now, we make do with Red Cross’s funds,” he says.

The lack of geriatric care in the country is an acute problem. “People don’t want to work for old people or clean anybody. They just want white-collar jobs,” explains Mishra. Government policies should be ‘ageless’, he says, citing the 18 per cent GST on eldercare services and the recent draft of the education policy. “The government of India stops the policy at 40. There are millions of illiterate people above 60. Why can’t they learn? Sports policy in India is for the youth. The policies of the ministry of women and child development don’t talk about older women,” he says.

At the Anugraha centre in east Delhi’s Shahdara, people have gathered on a Saturday to celebrate the birthdays and marriage anniversaries of the month. Children and grandchildren provide back-up entertainment as the elderly croon Bollywood hits from the sixties.

Rajkumari, 75, works as her daughter’s assistant.

One of them is former educationist Rajkumari, 75, who is an invaluable asset to her daughter Aabha. “I work as her assistant,” she beams. The centre assists its members with facilities like legal aid and a clinic, aside from being a community space where everyone participates in day-to-day activities. As we speak, music can be heard in the community hall outside. “If they dance in their homes, people will say buddha pagal ho gaya hai (the oldie has gone senile),” she smiles.

Pradeep Vashisht, 64, is a doctor.

“I started coming to the centre in December and nowadays I’m here daily,” says Pradeep Vashisht, 64, who lost his wife last year. “We were both doctors,” he smiles. He lives alone and runs a clinic where he attends to patients between 7 and 11 in the morning and evening. His son works in Mumbai and they meet about every two months.

Bimla Sharma, 78, visits the Anugraha daycare centre every morning.

Another regular visitor is 78-year-old Bimla Sharma, who comes for two hours in the morning. Her husband died when he was 45. Her son resides in Canada and her daughter, who lives nearby, often visits her at the centre. “Never be scared of anyone. Be afraid of fear,” says Bimla, making mock-fear gestures.

However, old-age homes are not a solution as many consider these a place to die rather than live. Most geriatric homes do not have any activities for community-building, regulatory standards or monitoring procedures. Another problem is that senior citizens collectively lack a political voice—they are not as organised as an interest group, nor have they made a consolidated push for their demands.

To truly empower the elderly community, there should be daycare facilities, 24-hour healthcare centres as well as services at home like meals and doctor visits. That is what will help the old folks of Bisaich, who now sit idle on charpoys and puff on hookahs, watching time slip by.