More than a century after Edwin Lutyens first began work on British India’s imperial capital, the neo-classical architect remains a household name in New Delhi, the city he designed. But until now, Lutyens’ Delhi has honoured him only in name. No museum bothered to introduce the public to the great architect, his work in India.

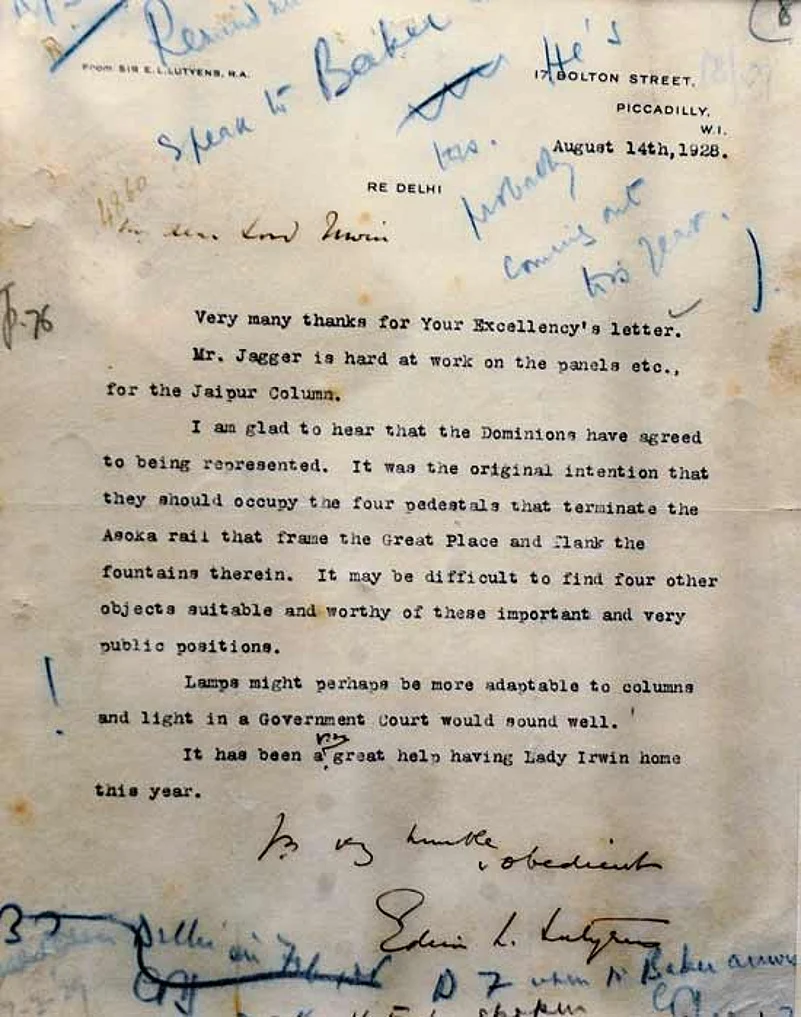

| A 1926 letter from Lutyens to Lord Irwin regarding progress on ‘Viceroy’s House’ |

The renowned museum-maker, Saroj Ghose, has designed it as a ‘storytelling museum’, a concept still new to India though it’s all the rage internationally. When the London museum group Historical Royal Palaces (its properties include the Tower of London and Kensington Palace) took to storytelling, its chief curator Lucy Worsley wrote: “We realised that our resources consist not only of five wonderful buildings, but also a rich store of stories.”

At its core, the Rashtrapati Bhavan Museum tells the story of New Delhi, covering a period stretching from the Delhi Durbar in 1911, when the shifting of the capital from Calcutta was announced, to the birth of the republic and the swearing in of Rajendra Prasad as the first President in 1950.

The New Delhi story is narrated in the coach house, while the stalls where once horses were stabled display a collection of kitsch or valuable gifts that various presidents got, such as a Chonma Chong gold crown from South Korea and a gold scabbard studded with precious stones from Saudi Arabia.

There is also a dramatic arms gallery recreating the Anglo-Sikh and Anglo-Afghan wars and a room dedicated to the President’s Bodyguard, the oldest regiment in the Indian army, raised in 1773 by governor-general William Hastings.

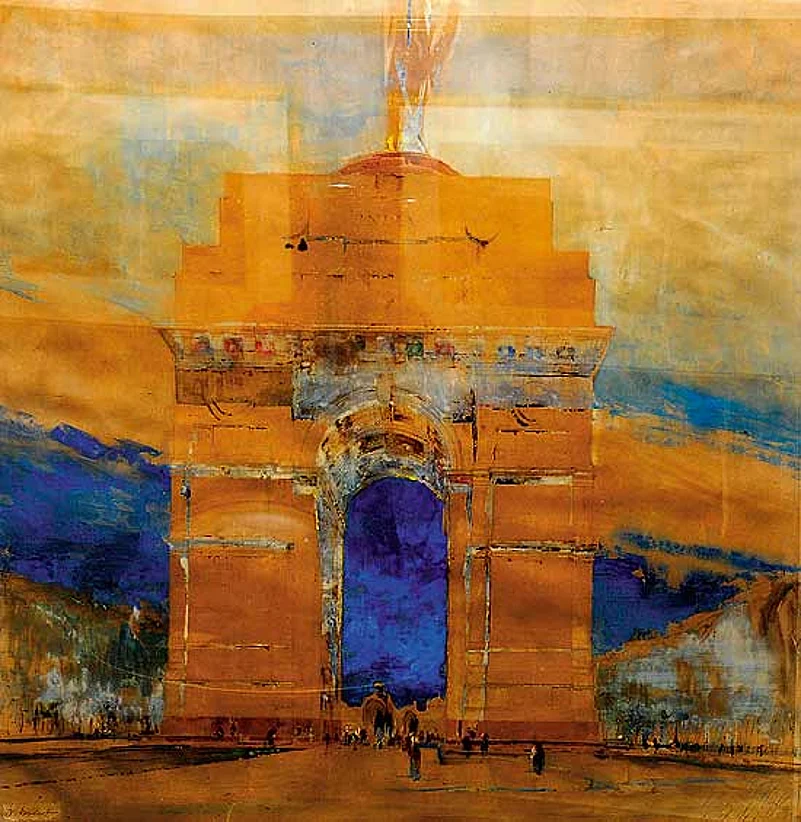

But for me the real highlight of the new Rashtrapati Bhavan Museum is its focus on Lutyens. On display are his letters, architectural drawings, furniture sketches and watercolours (often done in collaboration with an assistant), including a classic of India Gate that should be turned into a museum poster, and several of Rashtrapati Bhavan interiors. Watercolours by Lutyens’ rival, Herbert Baker, who designed the North and South Blocks, are also exhibited.

Lutyens’ letters provide a glimpse into his obsessive attention to detail, fretting about where a painting should be hung or how much of the furniture should be painted (rather than polished). Spread across almost all the stalls you can see the distinctive, often quirky furniture designed by Lutyens—tables, benches and five different types of chairs. They demonstrate the architect’s playful sense of design, inspired not just by geometry but also by natural forms, like a flower or even a spider’s web. As Candi Lutyens’ furniture reproduction website says of her grandfather’s style: “Precise and intricate mathematical details lend an element of surprise and Lutyens’ well-renowned love of jokes and ‘visual puns’ is self-evident in many of the tricks he employs.”

It’s not so well-known that a lot of the unique furniture that went into the 340-room Viceroy’s House (later the Rashtrapati Bhavan) was designed by Lutyens. A product of the Arts and Crafts Movement in Britain, he was an eclectic and prolific designer. From magnificent palaces and grand memorial arches to tables, chairs, garden fountains and even door handles, nothing escaped his keen and lively eye.

Some of Lutyens’ furniture has ended up in decorative arts museums, like the v&a in London, and even reproductions fetch high prices. The Rashtrapati Bhavan design demonstrates Lutyens’ ability to synthesise diverse influences, and create something unique. This quality is reflected in his furniture too. His granddaughter sees a connection: “The result is, like many of his buildings, absolutely controlled yet somehow astonishing—at first sight conventional, yet encompassing at a second glance both the whimsical and the paradoxical.”

A watercolour of India Gate by Lutyens

Lutyens, for instance, designed around 18 different types of chairs for Viceroy’s House. Unfortunately, after independence, due to neglect and misuse, quite a lot of the original furniture was destroyed or lost. Even the viceroy’s bed is missing. But a significant number of pieces were recovered and restored after Pranab Mukherjee became president, and some of these can be seen at the new museum.

Sadly, though the exhibits are a delight, no attempt has been made to tell Lutyens’ story or to introduce visitors to his architecture and furniture design. In a talk at the National Museum recently, historian Romila Thapar spoke of the importance of providing information that helps museum-goers understand the significance of exhibits. Lutyens, unfortunately, is let down by the grossly inadequate and sometimes incorrect labelling at Rashtrapati Bhavan Museum.

What’s worse, in the stables section of the new museum, visitors are not allowed to enter the stalls, making it impossible to properly view the exhibits. This misplaced concern with security has provoked the octogenarian Ghose to resign and return to Calcutta. But the new museum is only the first step in the president’s plans to ‘democratise’ Rashtrapati Bhavan and open it up to ordinary Indians. A 10,000-sq-ft museum space is being created opposite the stables, converting the old garages into a three-storey underground structure at a cost of `60 crore. Without Ghose, this ambitious expansion project will be a big challenge.

In a city with a rich history but a real paucity of museums (China opens 100 new museums every year), the birth of the Rashtrapati Bhavan Museum is something to celebrate. But though the new museum pays tribute to one colonial Englishman, it totally ignores another. New Delhi is popularly known as Lutyens’ Delhi, but its real founder was the viceroy Lord Hardinge (just as Shah Jahan was the founder of Old Delhi).

Hardinge is totally forgotten today. His statue, which used to stand at the foot of the Jaipur Column in Rashtrapati Bhavan, was removed to Kingsway Camp in the 1950s, and his portrait, which hung in the State Banquet Hall, was taken down in the 1960s. Elsewhere in the city, even Hardinge Bridge was renamed after Tilak. The story of New Delhi reconstructed in the Rashtrapati Bhavan Museum includes King George V and Queen Mary (and their heavy silver-and-gold chairs from the 1911 Delhi Durbar), but no Hardinge. It’s time the real founder of New Delhi also got his due.

(Maseeh Rahman writes for The Guardian from Delhi)