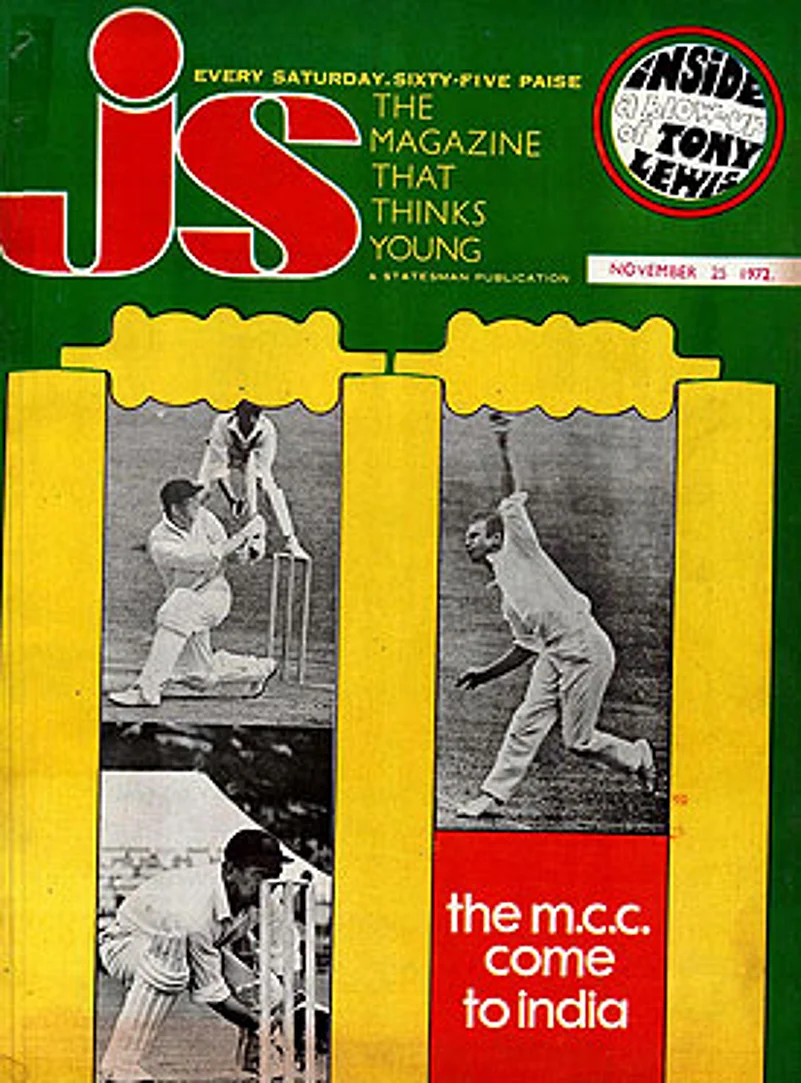

I had my first story published and met my first gay person at the same time. The connection was a magazine called the Junior Statesman. Or rather, its editor Desmond Doig, a larger-than-life figure and a legend in the Calcutta of the 1970s. Writer, photographer and artist, he was one of the stars at Statesman House when he was deputed to bring out a youth magazine. The title, Junior Statesman, was terribly unimaginative, but the magazine he finally produced was anything but. In the mid-1970s, Calcutta was the most happening city in India, and the JS, as it became known, reflected that, and lots more. For youngsters across the country, and college students like me, it was a cultural touchstone. I was in my final year at St Xavier’s College when I met Desmond at a social event. We got talking about college and careers, and before leaving, he asked me to write something and send it to him. I did, and he ran it in the very next issue. He hadn’t changed a word, which convinced me I had a future in the writing trade. I called up a friend in the Statesman to give him the good news and after the congratulations, he quietly added: “By the way, he’s gay.” Not gay as I was, having made a career choice for myself. The eureka moment, as some would call it.

| Trusty launchpad Junior Statesman was where the author, and quite a few other journalists, broke into print |

In the mid-1970s, India’s magazine market, like Mother Hubbard’s cupboard, was quite bare. There was the Illustrated Weekly, venerable and old-fashioned, and a handful of other periodicals that focused on women, sports and Bollywood. JS was the liveliest, but Calcutta-based. And while the majority of the existing magazines were Bombay-based, the capital of India’s publishing world was, well, the capital. It even had the equivalent of London’s Fleet Street—Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg, dominated by the Times of India, which had a monopoly on the magazine market, publishing Filmfare, Femina and the Illustrated Weekly. My ambition was long-form journalism, which would involve a long train journey, with the advantage of availing of the services of A.H. Wheeler, the bookstand on almost every railway platform, which stocked every magazine printed in India. Going through the ones I had bought, with employment in mind, there was one inescapable conclusion: they were as bland and boring as the food served by the railways. The only ones with some spark were the film magazines—not my chosen field. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail, and Capote’s In Cold Blood had hooked me to their method of strict adherence to factual accuracy combined with the use of literary techniques to flesh out people, places and situations to present a holistic picture of whatever or whoever was the subject.

Reading through the pile of magazines also inspired another thought: magazines tell us more about a country and its culture than its monuments and libraries. India in 1975 was stuck in a time-warp. Profiles of personalities were always in the past tense, obituaries were hagiographies, even if the subject was the biggest crook on the planet; reporters and writers were largely anonymous and there was little criticism of anything or anyone, especially politicians. The newspapers did break stories, but magazines were largely uninspiring. Then, a funny thing happened on the way to the magazine stand. It was called India Today, also not a very inspiring title—till I answered the ad and became its first (poorly) paid employee. The rest of the staff was from owner Aroon Purie’s family, plus a couple of their friends. I was attracted by their liberal views and the fact that New Journalism was their bible as well. The rest, as they say, is history. India Today, launched ironically during the Emergency, would go on to pioneer a new journalism in India, breaking the self-imposed shackles on creativity, existing taboos and holy cows, and spark a media revolution. The phenomenal success of the magazine in its initial years was proof that the Indian magazine market was ready for a totally new style of reporting, writing, presentation and photography.

The Bosses Newsweek and Time were perhaps the American magazines that were most popular in India

That style of journalism may have borrowed heavily from Time and Newsweek, but it was new for India, new and bold and innovative and inspiring. Having been part of the launch team, and having worked there for many years after, I could see its impact on the rest of the media; newspapers started to do more long-form writing, features and profiles, giving photography more space and attention, encouraging individual styles and bylines; more investigations; catchier and more contemporary formats, headlines and captions; and above all, doing what journalism does best—exposing the rich and powerful while also examining the unseen corners of society. The magazine boom that followed was inevitable and changed the Indian media landscape like nothing else before. There were magazines to cater to every interest and speciality, some would flicker and fade, others would go on to carve out their own individual space, but in the end, magazines found their place in the Indian sun. Content was king. Fast forward 20 years, to 1995, and the second magazine revolution got underway. A new generation of young readers had emerged, technology had changed the way news was covered and presented, and magazines reflected that more than the rest. Newsmagazines led the charge. Outlook was launched as a weekly, and India Today was forced to change from a fortnightly to weekly. The pace was speeding up. There was a generational change in politics (Rajiv Gandhi replaced his slain mother), in society, in consumers, in the cars we drove, the clothes we wore and the food we ate. The new generation came with new interests and concerns, and magazines reflected that change more than other forms of media.

That also introduced a new breed of journalist—the domain specialist. Till then, media outlets had political writers, a business and economy desk, crime reporters, city reporters, a sports desk, film critics and those who were in the general category. A handful had foreign correspondents. The new areas of interest and concern among readers required magazines and newspapers to bring in people with expertise in specific areas—environment, health, technology, automobiles, urban affairs, fashion, even food. There were cover stories on subjects like stress and sexuality, diets and designers, weddings and vacations, parenting and puberty, fitness and fads. It was almost an entirely new editorial menu compared to just a decade earlier. ‘What’s the cover story?’ became a familiar ritual at editorial meetings because everything was changing so fast. It was a brave new world and it required brave new journalists. The old order was changing, more so with the arrival of independent television news. Loud, in-your-face, instant, visually arresting and addictive, news television, like newsmagazines before it, would attract journalistic talent, this time with the lure of appearing live on national TV. Magazines and newspapers lost many stars, but more than that, TV news presented a new challenge: the channels were breaking news, analysing it and doing stories with powerful visual impact. It may have been shallow, short-lived, sensational, but newspapers and magazines were forced to adapt and evolve. Even as they struggled to do that, a bigger threat loomed: the internet and digital media. For a while, confusion reigned, advertisers dithered and obits started to appear for print media.

Old School India Today was launched with a team that looked up to Life, Esquire, Rolling Stone

They were greatly exaggerated, but the basic tenets of journalism were now under stress. The purpose is to give people the information they need to make better decisions about their lives, society and the people who rule them. Journalism is ultimately about credibility, and television and a highly fragmented digital media had blurred the lines. Magazines and newspapers took the only way out: launching their own digital doppelgangers, basically twin products, one a periodical and the other constantly updated and expanded. In America, the Association of Magazines changed its name to Association of Magazine Media. The cross-platform approach is now the new normal, and it comes with one advantage: greater interaction with the audience and instant feedback. The digital space may be encroaching on print but there is one great advantage magazines have—they remain a very visceral, tactile experience and many of them are brands with a reputation built over time and loyal readers. Magazines are built around passions, and in the digital era, it brings another positive. With the tsunami of content bombarding the consumer, it becomes an oasis.

Yet, the defining mantra of 2015 is that there are no constants anymore. The world is in transition, the global economy is in transition, society is in transition. What is ‘modern’ today will be history tomorrow. What will remain constant is the engagement of readers with magazine brands, regardless of device or platform. Magazines are sustained on the twin pillars of passion and community. Ultimately, they are made for writers, unlike newspapers, television or digital media. To come to the end of a compelling, beautifully crafted story, and to take a deep breath, is a feeling like no other. Which is why, at every editorial meeting, we still continue to ask the question: What’s the cover story?

Dilip Bobb was a member of the team that launched India Today in 1975. He has also done stints in Indian Express and NDTV. He has edited The Equator Line, an anthology.