Okay, straight payoffs first. Freedom. Explains Rana Mukherjee, a Supreme Court lawyer in his early 40s: "I enjoy my freedom immensely. I know happiness." Another is a sense of engagement with life: Sharupa Dutta, 34, film producer and theatre person from Delhi, says, "I have a life that isn’t mediocre; why trade it in for a dull married life?"

Shahrukh Annu Rutta, Delhi A World Bank consultant in her mid-30s, she indulges her passion in sculpting in Delhi when she’s not in Washington, or touring Africa, South America and Asia.

Two recent bestselling books neatly illustrate the contrasts between yesterday’s and today’s singles. Four years ago, New York Times Magazine featured an article by journalist Ethan Watters that looked at why his generation of Americans was postponing marriage—the group between 25 and 39 that is unmarried is one of the fastest growing in the country. Watters eventually spun his analysis into a book, the runaway success Urban Tribes. In it, he suggests that for the educated people in this age group, the network of friends, acquaintances and co-workers plays all the roles that the family traditionally did—protecting, nurturing, encouraging, inspiring. So much so that this has almost obviated the need for marriage.

While this is essentially true only for people like Watters himself (college-educated, white and at least middle class), it’s clear that the theory may also sit well among a small yet significant section of urban Indians. Like people Watters describes, they are less keen on following the nesting instincts than on finding meaning and fulfilment in the larger community of friends to which they belong. The other book, Sasha Cagen’s Quirkyalone: A Manifesto for Uncompromising Romantics, also accurately identified an entire cohort of people that had thus far eluded easy categorisation. These are people who are quite happy being single. Though they enjoy being alone, they also enjoy company, which is why relationships do develop. But one key caveat: though they may enjoy being in a relationship, they certainly do not pursue one just for the sake of being one half of a couple. The things that matter to quirkyalones—self-respect, confidence, creativity—are not necessarily connected with their relationship status at all. This is very different from a couple-centric social order, where so much is defined by relationships and their formalisations, like matrimony, child-rearing, inheritance, taxation and the law. In India too there is an excellent tome by Sunny Singh—Single in the City: the Independent Woman’s Handbook.

Of course this still begs the question of whether singlehood by choice is simply a matter of ducking the seriously big responsibilities of adulthood—marriage, procreation and parenting. Is today’s rising number of singles simply a sign that this is a generation of shirkers more interested in hedonism than hard work? After all, on the issue of responsibilities, not everyone is as upfront as Bangalore-based playwright Mahesh Dattani, who says marriage and comparable serious partnerships require careful negotiation and restraint, for instance, the need to be faithful, for responsibility, or to raise children in a certain way."This is completely unacceptable to me," he says. "I guess I am a bit of a hippie at heart." For Dattani, singlehood therefore becomes a natural state of being.

Responsibility aside, it doesn’t help that in much of common social perception, single people are assumed to be loose, if not outright deviant (see box: Sex and the Pity). Pritha Sen, a social sector consultant in her forties, describes the intrusive questioning women in particular have to face while they’re house-hunting (Questions about age, salary, drinking habits and the sort of ‘friends’ who might be visiting are normal): "A cousin who was looking for a house for me was asked if I was a ‘virgin’! He almost beat up the man till he realised he was actually only being asked if I was single!" she says. Several single heterosexual men have had to explain that no, they are not gay, and no, they aren’t immediately interested in matrimony or children either. It’s more than just sexuality that gets called into question. Sen talks about an acquaintance who assumed single women had no structured life or routine, went out all the time, and ate junk food. Aseem Mishra, an advertising filmmaker in his late thirties, who recently moved to Mumbai, has also faced this. Which is why he’ll swear that he bathes every day, wears clean underwear, and, surprise, surprise, even loves staying in at home.

Personal hygiene and personal discipline aren’t the only issues. There’s a sense the single person is somehow incomplete, especially if she’s a woman. Tuba Jain is in her early thirties, from a prosperous business community in Old Delhi. She took over her family business after her father died. She continues to run the business, drives her own car, and defines the contours of her life. She is in several ways her own person and the envy of younger women in her social group. Yet for her, "Family functions are a nightmare. Older women just don’t stop throwing me questions about marriage. My only defence is my sense of humour." This apart, living alone comes with many irritants, annoyances and genuine problems (see box: 10 Hassles of Being Single). So is there something quite special about the contemporary state of single life that attracts individuals like Sen, Mishra, Dattani or Jain?

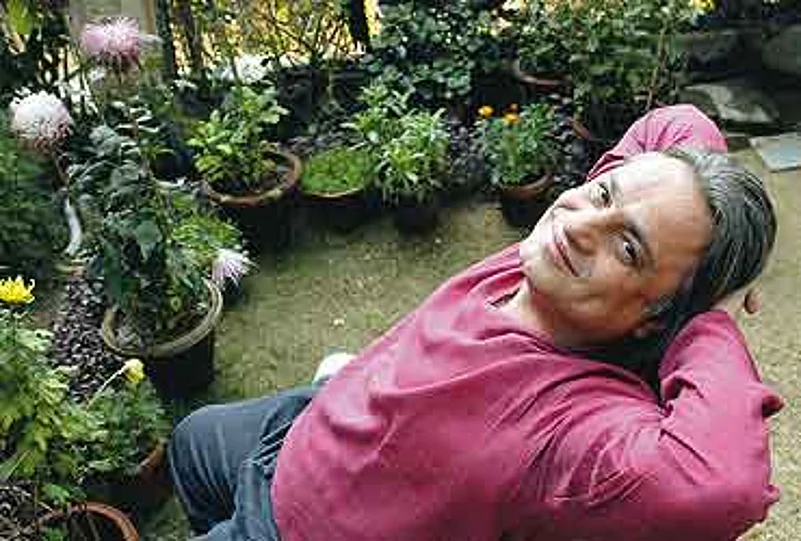

Rana Mukherjee, Delhi A Supreme Court lawyer in his early 40s, who turned single after 10 years of marriage, says he now "knows happiness". "I can choose which side of the bed to wake up.I’ve now taken charge of my life."

Those luckless bachelors and spinsters of yesteryear rarely had the luxury of choosing their status. Until recently, polite civil society simply lacked the syntax to say that bachelor uncle was gay or had psychological problems that precluded healthy relationships. And it certainly grappled with spinster aunt’s remarkable lack of good looks or her terrible horoscope.

Sharupa Datta, Delhi Says this 34-year-old film producer and theatreperson from Delhi, "I have a life which by no means is mediocre, why should I trade it for a dull married life?"

Today, for many middle-class Indians, the socio-economic world has changed faster than language or attitudes. Which is why we still struggle—and fail, of course—with early 20th century terms of reference to describe "spinster aunt" who went to IIM Ahmedabad, makes almost a crore a year as an investment banker, and really gives a rat’s tail-end about what some clown thinks about her looks or horoscope.

Choice.Rising incomes and the possibility of a decent quality of life mean that it is no longer financially imperative for two or more people to stay together.This has created a viable option for men. But for women it means much more. The choice to adopt children to experience motherhood. Mamta Govil, a teacher in Delhi, has still not met the man she wanted to marry.But she did not want to miss out on motherhood. So, she adopted a baby girl last year. "I had a full life on my own but this is moving on in the most beautiful way," she says.

Dattani’s understanding is that the modern world no longer derives identity and self-worth purely through marriage and procreation. There are other avenues. Sometimes this is as simple as having the power of self-determination, or the freedom to choose who you are.Consider Oindrilla Dutt, 46, an event manager from Calcutta who comes from a family of "doctors and doctorates", who chose never to be married. When friends tried to hook her up, she found herself "thinking too hard for excuses to cop out". Today, with a flourishing career and vast network of friends, she could not be happier. "I love my freedom. I love being my own person and never having to be answerable for any lunatic thing I do."

Sarita Ganeriwal, Bangalore For this textile designer from an orthodox Marwari family of Calcutta, "singlehood is a deal you cut with yourself.... It is all about guarding your space."

It’s also why Sarita Ganeriwal, a Bangalore-based textile designer, says "singlehood is a deal that you cut with yourself". She comes from an orthodox Marwari family from Calcutta but has carved out a life of her own. Having studied in Delhi and Baroda, she now has a life full of work, friends and freedom. "My singlehood is not about banishing others; far from it. But there are also times when I don’t want anybody around. I guess it’s the same with married people." She quotes, appropriately enough, from psychiatrist Victor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning: "I am happy because I choose to be happy."

Kushal Biswas, Calcutta An Eng Lit lecturer just on the other side of 40, he loves being able to take snap decisions, go out for dinner at short notice or be with friends without having to worry about if his partner will mind

Freedom with responsibility is likewise a cornerstone of Kushal Biswas’s life. The English lecturer from Calcutta talks about how he can take snap decisions, go out for dinner at a short notice and be with friends without a worry about whether his partner will mind or not, while at the same time being there for his three sisters and elderly father. World Bank consultant and sculptor Annu Ratta also chose freedom for its flexibility. She spends part of the year in Washington and touring Africa, South America and Asia, and is a sculptor the rest of the time. She sculpts in a recently bought flat in South Delhi, a four-hour drive away from Chandigarh, where her parents live. "I love life too much and would not get stuck in one place. I have found love in many places and people and never found the need to be married."

Going Solo, Mumbai A singles club of 1,800 members who meet up twice a month. Many young people who come to the city work long hours but like to meet people like themselves and have someone to celebrate with

Freedom also means financial independence and spontaneity.Says Rekha Sethi, a senior director with CII in Delhi: "I go to interesting places all over the world with my friends whenever I can." Ganeriwal would agree: "The other day my friends and I thought we should go on a holiday, so we just packed our bags and left." Despite the connotations of loneliness, singledom’s particular brand of freedom can also mean community, something from which the people described by Watters and Cagen draw enormous sustenance. In Mumbai, radio jockey Malini Aggarwal has set up a social club, Going Solo.The 1,800 members meet as often as twice a week. "Many young people come to Bombay, work long hours but like to meet people like themselves so they don’t feel alone and have someone to celebrate special occasions with," she says.

Going Solo is no matchmaker.Its roots, and those of today’s new singles, derive from the thinking of a hapless psychiatrist the Nazis flung into a concentration camp. Victor Frankl spent his time at Auschwitz putting together one of psychology’s most germinal works. He was one of the first to disagree persuasively with Freud’s theory that man’s sexual instinct determined much of human behaviour. Frankl passionately believed that a need to search for meaning and purpose was more important.

There is, and it’s called choice.

Amit Saigal, Delhi The publisher and editor of Rock Street Journal who was "un-married" three years ago, says he rediscovered the rhythm in himself and had taken up playing after many years.

Rock Street Journal editor Amit Saigal, thrust suddenly into singlehood not long ago, would agree with those issues of meaning and purpose. "I love a lot of people and a lot of people love me back. I think I had started taking life a tad more seriously than I should have.Life’s just a little act," he laughs. With a happy middle and a happy ending.

By Sanghamitra Chakraborty with Labonita Ghosh in Calcutta, Sugata Srinivasaraju in Bangalore and Saumya Roy in Mumbai