For 42-year-old Rajdeo Ranjan, Friday, 13th May 2016, would have been a usual day like any other. But unfortunately, for him, it was his last. He was shot dead at point blank by criminals in an open market place.

Ranjan was the Bureau Chief of Hindustan—a leading Hindi daily— posted in Siwan in the state of Bihar. For decades, he had been vocal in his writings about the misdeeds of local politicians involved in serious crime and corruption. Prominent among these were the acts of former Member of Parliament Mohammad Shahabuddin. Presently, he is serving a life sentence in a case involving him in abduction and murder of two people in 2004.

This was the second such case in less than 24 hours in India. A day earlier, another journalist, Indradev Yadav, from a Hindi news channel in Jharkhand was shot dead.

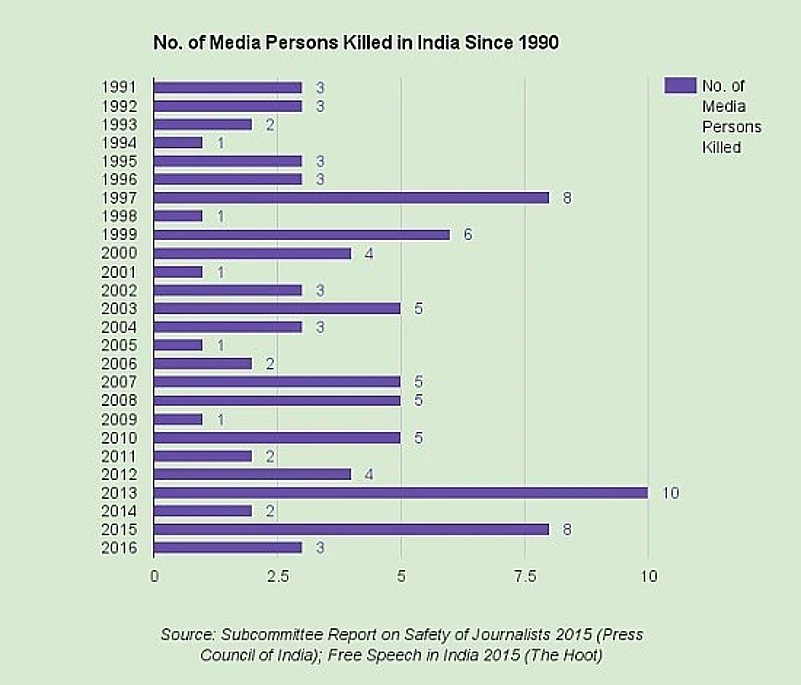

In 2015, as many as eight journalists were killed in the country.

How serious is the situation?

According to the 2016 World Press Freedom Index published by Reporters Without Borders, India ranks abysmally at 133 out of 180 countries. The rankings are a reflection of the relative degree of freedom journalists enjoy in a country. The factors that determine the index are - pluralism, media independence, environment and self-censorship, legislative framework, transparency, infrastructure and abuses. (The details of the methodology can be found at https://rsf.org/en/detailed-methodology)

Until 2014, no separate data on the cases of crimes against media persons was officially maintained in India. The National Crime Records Bureau, since 2014, has started collecting this data.

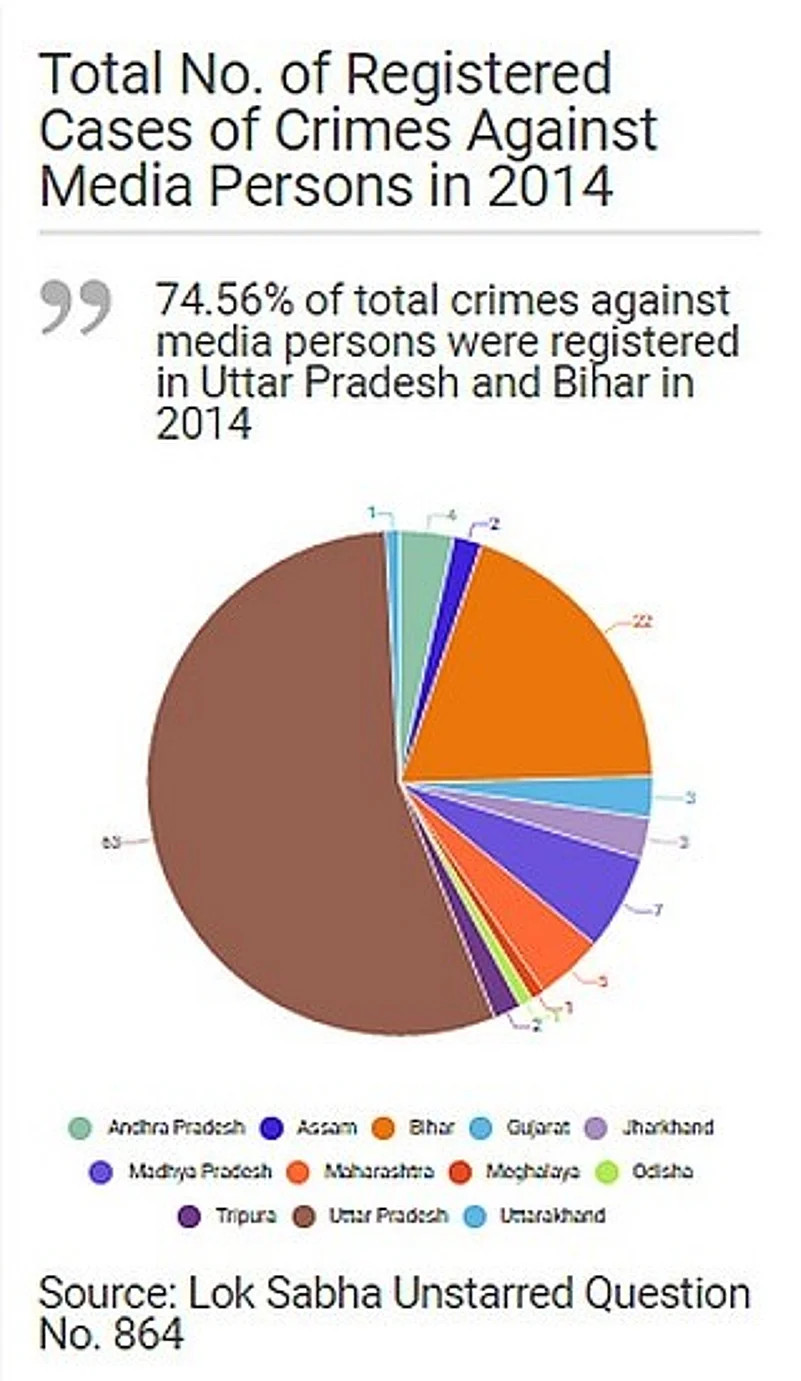

The government in response to a question in the Parliament recently stated that "as per the available data, a total of 114 cases were registered and 32 persons were arrested under attack on media person during 2014".

This effectively means that every week at least two media persons are attacked in India. (Given the country's poor rate of registering cases with the police, this figure can actually be higher on ground.) Interestingly enough, the crime statistics is not evenly distributed across the country. 74.56 % of the total registered cases of crimes against journalists in 2014, occurred in the two states of Bihar (22) and Uttar Pradesh (63).

The Parliament of India, in 1966, established the Press Council of India (PCI). In papers, this is to serve as an authority where complaints against (and by) media persons can be registered and investigated. It is headed by a retired judge of the Supreme Court. However, in practice, the council is best described as a 'toothless tiger' because its ruling has no binding effect on the guilty. The council only has the power to recommend.

Furthermore, broadcast journalists are not covered under the PCI.

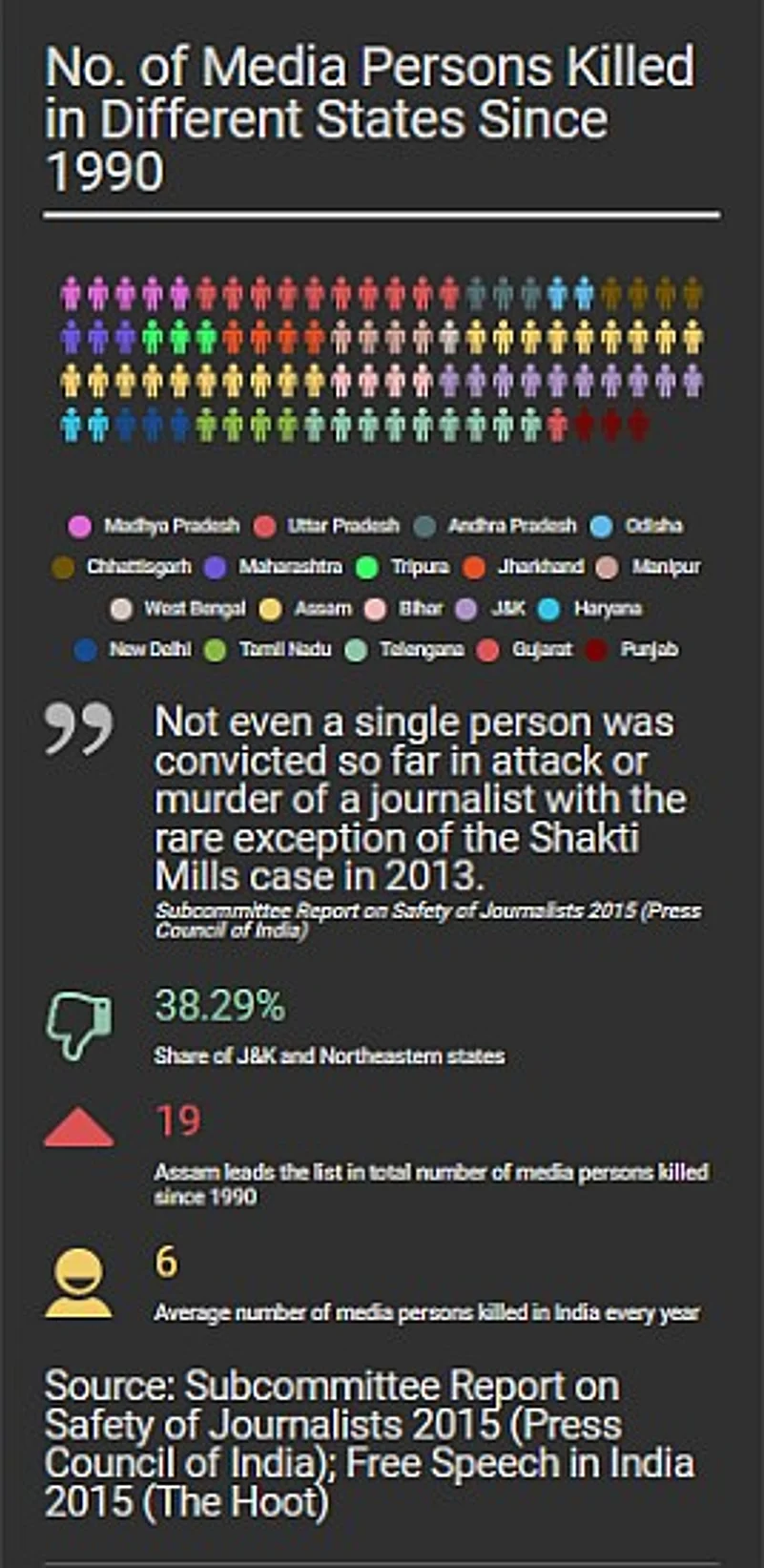

According to a 2015 report by the PCI, titled 'Subcommittee Report on Safety of Journalists', 80 journalists and five media persons have been killed in India since 1990. By May 16, 2016 the total figure has risen to 94. (See infographics)

In the report, it was also found that "in states like Assam, Andhra Pradesh, Manipur, Jammu & Kashmir, Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand, not a single person was convicted for killing or attacking the journalists."

Veteran journalist Rahul Jalali, the President of the Press Club of India, explains the ground reality of journalistic freedom in the country. On a Facebook post he writes, "Nowadays being an honest journalist is one of the most hazardous jobs going. As Press Club of India President, almost every day I get appeals from journalists in small towns of the perils they face. In the absence of any redressal mechanism we have nowhere to go."

"Also the manner in which our politics and society is moving, we are easily targeted and often lose our lives. The latest are our two colleagues from Bihar and Jharkhand. In other professions they might have been called martyrs who died to defend the truth, but alas we don't even acknowledge this fact."

Even though the figures suggest that the problem is alarming, it would be preposterous to say that India is a graveyard for journalists to work in. Crimes against scribes is a law and order problem in India. It is not a state policy to kill or attack scribes like in dictatorial regime elsewhere. This distinction should be maintained.

However, the government (Centre and State) cannot escape answerability.

Reporting in an environment of economic uncertainty:

Journalists in India face threats on several fronts. Criminal violence is just one of the many such threats. Apart from this, media persons in India are vulnerable to financial uncertainties in the form of inadequate salaries and large scale job cuts.

Technically, the Working Journalists and other Newspaper Employees (Conditions of Service) and other Miscellaneous Provisions Act, 1955, does protect the interest of working journalists in India. It does mandate several safeguards for gratuity, working hours, leave and revision of wages according to the recommendations of the Wage Board.

However, the Act is rendered meaningless by Section 18 of the Act which states that "if any employer contravenes any of the provisions of this Act or any rule or order made thereunder, he shall be punishable with fine which may extend to two hundred rupees ($2.99 only!)." A fine of just $2.99 is meaningless to act as a deterrence. Furthermore, if the employer is convicted for a second time under the same provision, the fine may extend to five hundred rupees ($7.48 only!).

The scenario gets further complicated with frequent large scale job cuts in the name of 'down-sizing' and 'multitasking'.

The PCI report quoted above, also mentions these problems being raised by journalists in different states.

To silence, drag the reporter to the court:

Apart from the violent attacks and economic uncertainty, the freedom of the media in India, in certain measures, is also curtailed by the sinister use of defamation and sedition laws to silence journalists. Journalists and media houses, more often than not, find themselves dragged into courts under these laws. Repeated court summons force most media houses to impose self-censorship on their reporting.

According to the annual report on free speech titled 'Free Speech in India, 2015' by The Hoot—an independent media monitoring website—there were 48 cases of defamation and 14 of sedition registered against media persons and artists in India in 2015. Furthermore, according to a report in The Telegraph published in December 2015, the Jayalalithaa led Tamil Nadu government alone filed a total of 190 defamation cases in its tenure.

The Supreme Court of India in a recent verdict has upheld the constitutional validity of criminal defamation.

If the present infatuation for using defamation and sedition laws to silence journalist goes unabated, the 'world's largest democracy' will be soon brokering hard hitting investigative journalism for political correctness.

A note of hope:

Criticism of media is no doubt a healthy exercise. It is absolutely necessary in a democracy. But should we also not spare a thought when journalists are murdered in broad daylight and defamation suits are slapped with malafide intent to censor the media?

Unless the society as a collective supports the freedom of press, the tragedies like that of Rajdeo Ranjan and Indradev Yadav will continue unabated. The headlines will fall on closed eyes. The cries of the families on deaf ears.

Whether a democratic society can afford such restrictions on the media, it is for the society to answer it.

Mukesh Rawat is a New Delhi-based freelance journalist. Twitter: mukeshrawat705 Mail: mukeshrawat705[at]gmail[dot]com