Large stretches of Uttan Road in Bhayandar, a distant Mumbai suburb, are brightly lit urbanscapes. There are modern residential complexes, a mall, a McDonald’s and several other restaurants. But a short detour from the main road takes one to the shockingly different world of Murdha Gaon. It is pitch dark and swampy. There are salt pans around and the air carries on it the fungal notes from the Vasai creek nearby. Alongside the bumpy path are huts built from tin sheets and assorted scrap.

In these challenging surroundings, a small movement of wrestlers is afoot. Every morning and evening, boys and girls from the neighbourhood head to Jai Malhar Kushti Sankul (wrestling complex), a ramshackle but fairly large space comprising a big round blue mat, an akhara (traditional wrestling school)-style mud-pit smelling of camphor and lemon, and two thick, 25-foot ropes for students to clamber up and down. A few feet away, standing in semi-darkness, is a black and white cow, whose job is to provide milk for the trainees. The sankul was built about a year ago by its president, Gorakh Khaladkar, along with Netaji Subhas National Institute of Sports (NSNIS )Patiala-trained coach, Premchand Akkole, and other well-wishers.

The sankul encourages girls, even though it has strict rules. Their hair must be short and occasionally Akkole smacks erring students with a cycle tyre tube. Not the most inviting context for a female wrestling aspirant.

Their star, however, is 18-year-old Aishwarya Sanas. True to the pehelwan (wrestler) tradition, she touches the feet of all elders around, including this reporter’s. “When I started wrestling, people would say, ‘What is she going to do?’ They would say a lot of things behind my back,” says the bespectacled Sanas. “But I have my parents’ support.” Sanas is a third-year Arts student at SST College in Ulhasnagar. She is also in the process of appearing for physical endurance tests for a job with the Mira-Bhayandar police force.

As a wrestler, she is aiming high. “I want to make it at the international level,” she says. Being a young collegian, doesn’t she want to grow her hair? “Savay zhali,” (I’m used to short hair now) she says. “We live like boys.”

Coach Akkole, slightly apologetic, explains his reasoning. “We are not saying, ‘Do only wrestling and nothing else’. But there is a time in life for enjoyment or dressing up,” he says. “The day your career is made, you do as you wish. But for now, it’s ghodyacha chashma (a horse’s blinders).”

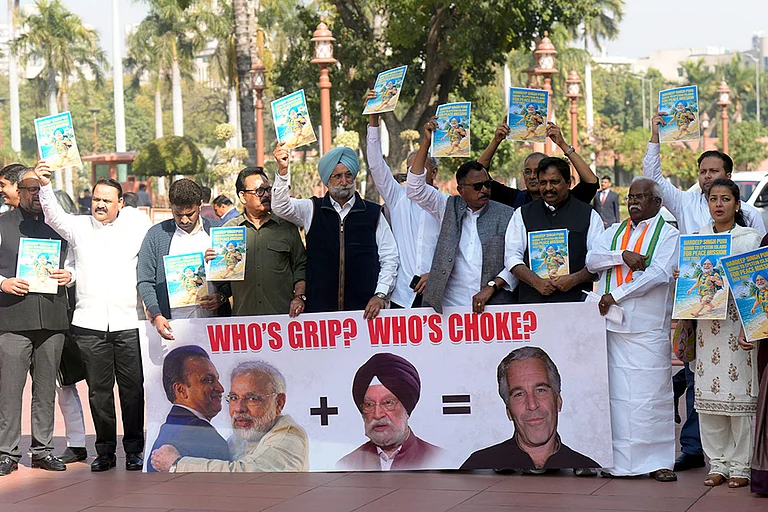

A few days ago, star Indian wrestlers such as Vinesh Phogat, Sakshi Malik, Bajrang Punia and Ravi Dahiya accused the Wrestling Federation of India’s (WFI) president, Brij Bhushan Sharan, of sexual and mental harassment. When Outlook asked Kaka Pawar, Arjuna Award winning grappler, coach and administrator from Maharashtra, for his response to the matter, he declined to comment. But he did speak about the importance of providing a safe environment for girls to train in.

An old-school son of the soil from Latur, Pawar would rather have girls train and travel with a woman coach or staff. “I have some 400 students but I haven’t trained women wrestlers precisely for that reason. I feel women wrestlers are better off training with female instructors. Things are more open abroad but then our culture is different.”

With or without female instructors to protect them, Indian women have walked a brave path towards sporting excellence in wrestling. Not everything is gloom and doom for Indian women athletes. But rare is the Indian sportswoman who has not faced gender discrimination, overt or subtle.

“Though I do believe things are getting better, what we have to address and accept is that we are living in a man’s world more than in an equal world,” tennis star Sania Mirza once said. “Stereotypes and biases exist in every profession. You need to speak up for yourself and command the respect you deserve. I have been taught that as long as I am doing the right thing, I need to speak up.”

Mirza recently retired after a path-breaking career in which she reached world No. 27 in singles and no. 1 in doubles. Coming from a middle-class, urban family, she was spared the socio-economic horrors that female athletes from rural India have to endure. But she did have to face several other challenges—such as criticism from conservative quarters on matters such as the propriety of her tennis outfits. Playing in the internet age also meant judgments about her body and guilt-tripping her about the amount of time she was spending with her son.

“Patriarchy is present and it needs to be acknowledged,” Mirza said in an interview. “If you’re asking me where my child is when I’m sitting at a press conference after winning a tennis match, then do the same to my husband. And if you are not asking him, then don’t ask me.”

Gender-based Stereotyping of Women

The world of sports has long operated as a site of the perpetuation and celebration of a type of (heterosexual) masculine identity based on physical dominance, aggression and competitiveness. Men are paid more than women, treated better and given more publicity.

The feminist movement of the 1960s and 70s, across the world (including India) has not fought enough for women in sport but the creation of laws like the Title IX law in the US, which prohibits gender-based exclusion in any educational programme or activity opened the door for greater participation of women in sports and its many aspects, such as administration.

There is no doubt that women’s inclusion in the top echelons of sport is now greater and more visible. At the recent football World Cup, Stephanie Frappart of France led the first all-female refereeing team in men’s World Cup history. Frappart, along with Brazil’s Neuza Back and Mexico’s Karen Diaz Medina, officiated the Group E match between Germany and Costa Rica. Yamashita Yoshimi and Salima Mukansanga were also among the referees at the World Cup. “There are hardly any female referees in the Middle East, so I would like to see that change, with the Qatar World Cup as the catalyst,” Yoshimi says. “The fact that women are officiating for the first time at a men’s World Cup is a sign to people that women’s potential is always growing and that is something I also feel strongly about,” she adds.

In cricket, Australia’s Claire Polosak became the first woman to work in a men’s Test match. She was the fourth official in the third Test between India and Australia in early 2021.

A few days ago, Vrinda Rathi, Janani Narayan and Gayathri Venugopalan became the first women umpires to be chosen to officiate in men’s Ranji Trophy matches.

Tennis gold badge referee, Sheetal Iyer, is among the few Indians who have made a name for themselves as officials in an international sport. Initially, she had to work hard to gain the confidence of male players. But now she and many Indian women officials are fixtures at international tournaments. A few years ago, Iyer even oversaw a sensitive Fed Cup meeting between Israel and Ukraine in Ukraine.

“It was quite tense and I wasn’t sure how it would play out,” says Iyer. “I had not only to ensure the smooth functioning of the matches but also that all the players were safe. Everyone was cooperative, however, and it went off well.” A few days ago, Iyer was the chief official at an all-women team of umpires at an International Tennis Federation event in Pune. The very next day, she was heading to Lithuania, which she estimated was the 51st country to which she was travelling. The mother of a teenage boy, Iyer says she still gets raised eyebrows for leaving her husband and son behind. “To that I say, if a father can travel for work, so can a mother,” says Iyer.

When her son was little, Iyer herself would feel guilty about the travel, even though her family and in-laws supported her. “I missed many of his birthdays and school functions. But I knew that if I didn’t do those assignments, I wouldn’t have gone far in my career.”

Iyer points out that there was a woman— Louise Engzell of Sweden—in the umpire’s chair for the Australian Open men’s final between Novak Djokovic and Stefanos Tsitsipas. She also mentions former tennis player Manisha Malhotra and her current role as head of sports excellence and scouting at JSW Sports as examples of women’s importance at various levels of sport. “Women’s inclusion is no longer just out of tokenism anymore,” she says.

A Change in Mindset

Divya Kakran, a wrestling bronze medallist at the Asian and Commonwealth Games, believes there is a change in mindset of people towards women’s participation in sports. Originally from Purbaliyan village in Uttar Pradesh and now a resident of Delhi, Kakran observes this change even in the country’s smaller towns, which are typically highly conservative.

“When I started wrestling, it was difficult. Our outfits are figure-hugging, and we have to wear shorts. People would object to that,” Kakran told Outlook. “On top of that, we were poor. My mother would stitch wrestling ‘langots’(underwear worn by wrestlers) and my father would sell them. But I always had their support. They also explained things to others and gradually things changed. And then I moved to Delhi, where people’s attitude towards a girl taking up sport was much better. In fact, even in my village, there are now two or three girls who go to Muzaffarnagar for wrestling.” Kakran is also grateful for the government’s cash incentives for athletes, which, she points out, are the same for men and women. In 2020, she was conferred the Arjuna Award, which came with a purse of Rs 15 lakh. For her bronze in the 2022 Commonwealth Games, she received Rs 5 lakh from BJP MP Manoj Tiwari. This is the year of the Asian Games, for which the UP government has promised Rs 3 crore, Rs 1.5 crore and Rs 75 lakh to gold, silver and bronze medallists, respectively.

“This is a big thing for athletes who rise out of poverty,” Kakran says. “It inspires us to work harder. And there is pay parity between men and women as well.”