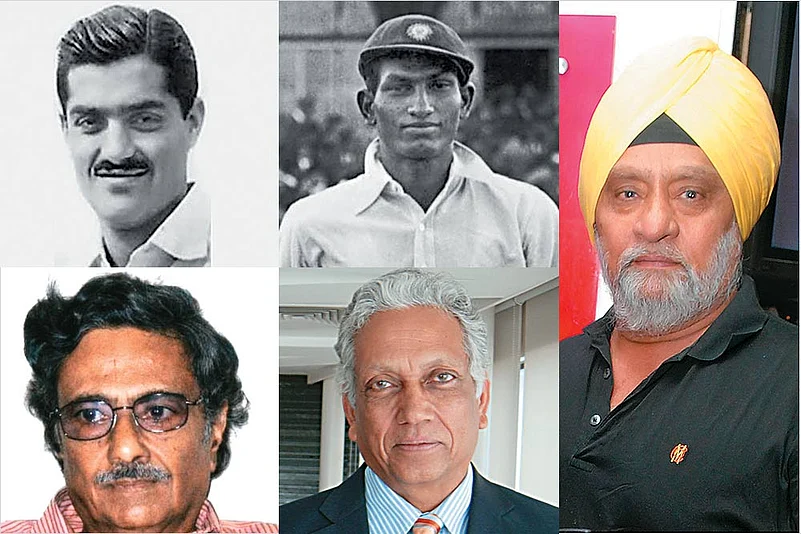

The doughty Mohinder Amarnath, the only Indian batsman of his generation who had the technique to regularly employ the hook against the fastest of bowlers in an age of untramelled short-pitched stuff, and who is also known for his many comebacks to the Indian team, was recently felicitated by the Delhi and District Cricket Association (DDCA), which also named a stand at the Ferozeshah Kotla after him. At the event, another stand was named after Bishan Singh Bedi. Unbelievably, it is only now that these legends of Indian cricket have got a mark of recognition in their home ground. In some ways, the gathering, at which almost all Delhi Ranji captains were present, marked the breaking of ice between the two Delhi stalwarts and the DDCA.

Both Bedi and Amarnath have captained Delhi to Ranji Trophy triumphs. Bedi was the pioneering captain who broke the Ranji hoodoo for Delhi in 1978-79. The illustrious left-arm spinner led the team to triumph in 1979-80 as well and after losing the next final to Bombay, Mohinder, whom Bedi had brought from Punjab to strengthen Delhi, emulated the feat in 1981-82.

However, both Bedi and Mohinder, who also represented Baroda, never got the due commensurate to their achievements and stature, either from the DDCA, Punjab, Baroda or the BCCI. Of course, both have been national selectors and have served as coaches of various states/national teams, and received BCCI’s C.K. Nayudu Award, the one-time benefit and get the Board’s monthly gratis for retired first-class/international cricketers. Also, Bedi became India’s first cricket manager in 1990. Yet Bedi and Mohinder have always been outspoken critics of cricketing matters and were seen as anti-establishment. So, both the BCCI and the DDCA never gave them their rightful due, until Delhi High Court-appointed administrator of DDCA Vikaramajit Sen decided to honour them, as well as Virender Sehwag and former India women’s skipper Anjum Chopra, besides Delhi Ranji captains.

“Of course, it’s a different time altogether. I am happy, and I wish these things continue in the future. Those who have contributed to Delhi and Indian cricket should get credit, their services should be recognised and they should be given respect,” Amarnath, whom Imran Khan once ranked as the world’s best player of fast bowling, tells Outlook. Sen, a former Supreme Court judge, is encouraged to do more. “Several cricketing legends from Delhi have now approached me with the offer to shoulder some responsibility. This response has brooked no opposition. If some of these greats, possessing administrative flair, can be drawn into running cricket, it will only benefit the game,” Sen says.

Amarnath, who famously called the national selectors a “bunch of jokers” in 1988, after being ignored for the Indian team, is not the only one to be treated shabbily. Although some cite the one-time benefit purse that the BCCI presented to Test and select first-class players in 2013 and the monthly amount that retired players/umpires have been receiving since 2004 as ‘recognition’—besides other awards and tournaments named after the greats—there are many who feel deprived.

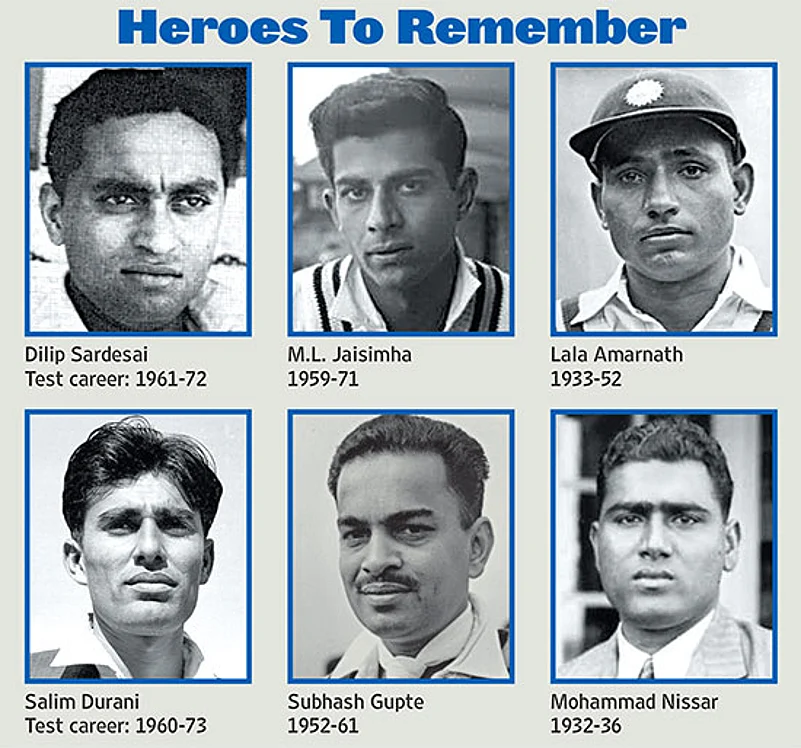

Players who haven’t got their due proportionate to their achievements and contribution are mostly from old times, when money and facilities that are taken for granted now were almost non-existent. This list (including some who are deceased) could easily include the likes of Mohammad Nissar, Syed Mushtaq Ali, Subhash Gupte, Deepak Shodhan, V.V. Kumar, Nari Contractor, Salim Durani, M.L. Jaisimha, Dilip Sardesai, Manoj Prabhakar and the Amarnath family—Lala and his sons Mohinder, Surinder and Rajinder. This, of course, is not a comprehensive list. Then, there were players, like Rajinder Goel and Padmakar Shivalkar, who were simply unlucky not to represent India, thanks to the selectors.

Some of these stalwarts have reconciled to their fate, though they at times fail to hide the tinge of regret that still pinches them. For example, Contractor, who was completely ignored by his home state, the Gujarat Cricket Association, tries hard to put up a brave face. “Recognition is such a broad word. There is no limit to recognition. Whatever comes, comes; whatever goes, goes. If people think of giving you something, you accept it. If they don’t, you don’t. After a certain stage, you have to have this attitude. I am a very contented man,” the Mumbai-based Contractor, 83, tells Outlook.

Although Contractor received a one-time purse of Rs 60 lakh from the BCCI, he was treated very shabbily by Gujarat. Narhari Amin, who was GCA president for 16 years (1993-2009), admits that the contribution of Contractor and other Test stars like late Jasu Patel and Deepak Shodhan were not recognised. “Yes, there are no stadium stands or any tournament named after these cricketers,” he says. There was talk that some years ago a stadium was proposed to be built in Godhra, Contractor’s birthplace, and was to be named after him. Old timers say that Contractor, so far the only Gujarat cricketer to captain India, at the time expected it to be the “only recognition that was going to come his way”. But even that did not happen.

The debonair Mushtaq Ali (1914-2005), the first Indian to score an overseas Test century (112 vs England, Old Trafford, 1936), didn’t get his due during his career and even afterwards. BCCI officials/selectors didn’t give him enough opportunities in Test cricket, despite his 32-year long first-class career. Then, in 1996, the Madhya Pradesh government gave the green signal to a cricket museum that Mushtaq Ali wanted to build in a bungalow in his hometown Indore. But an unexpected litigation ensued and his dream remained just that. “After his retirement, he was not even appointed selector, because he was a straight-forward person. He would say what he felt about something to someone’s face. That went against him,” says his son and ex-first-class player Gulrez Ali. Gulrez’s son Abbas also represented Madhya Pradesh and is now its Ranji team manager-cum-fielding coach.

Legendary leg-spinner Subhash Gupte, who bagged 149 wickets in 36 Tests in the 1950s, also apparently paid for an off-field indiscretion. “He asked the BCCI for a benefit match, but was not given one. I once asked Gary Sobers about the most difficult bowlers he had faced, and he said ‘Gupte’,” recalls well-known commentator Ravi Chaturvedi. He also reminds that Mohammad Nissar, who with Amar Singh was India’s greatest fast bowling pair, and which opened the bowling in India’s first-ever Test in 1932, also didn’t get the due he deserved. “He was a gentleman fast bowler, who bowled the first ball for India in Tests,” says Chaturvedi.

Another illustrious spinner, Bishan Singh Bedi, also got the rough end of the stick for being critical of the BCCI, though he has mellowed considerably. “Nothing went against me for my outspokenness. I don’t react anymore; I respond now. The naming of the Kotla stand is not a milestone for me. It just happened; I didn’t ask for it. Similarly, it just happened that I represented and captained India,” Bedi tells Outlook.

All-rounder Manoj Prabhakar—at one point he opened both the bowling and batting for India—was known for his tenacity. Banned for five years for his alleged role in the 2000 match-fixing scandal, he was a bit like Bedi and Mushtaq Ali—blunt. Naturally that was held against him. On his return after the ban, he became Delhi Ranji coach, but was soon shunned by the DDCA, while the BCCI hasn’t released his benevolent fund. In fact, at least Rs 1 crore (including the benevolent fund) of his is with the BCCI, which isn’t releasing it. “I have written several letters to the BCCI and to Vinod Rai, head of the SC-appointed CoA, but haven’t received even one reply,” he says. A born fighter a cricketer with guile, his services could also have been utilised as a bowling coach for the Indian team.

The Amarnath clan, perhaps, suffered the most of all. Lala Amarnath was a known anti-establishment man and his candid views antagonised the powers-that-be. And that, in some ways, impacted his three sons’ careers. Delhi and national selectors ignored Surinder, the eldest of the three and who scored a century on his Test debut, as he was part of the Bedi-led ‘revolt’ in 1979-80 against the then DDCA administration. After scoring heavily in domestic tournaments, he was a contender for the 1979 tour of England but was denied it. He was also ignored for the Australia tour in 1981. “It hurts when you are ignored after having given your best and performed better than the others. But that is past; I now want to serve the country and cricket, and I can prove that I can do it,” says the former left-handed batsman.

Recognition, however, is a subjective term and it isn’t necessarily about money alone, insists well-known commentator Narottam Puri. “The sentiment should be to remember the contribution of a person who has made a difference on that site or venue for the sake of history and posterity,” he says. Sudhir Vaidya, the doyen of cricket statisticians, has an advice for administrators. “Every cricketer should be honoured when he is at his peak, not after 10 or 20 years after his retirement,” he says. He is right. But those who have seen Bishan Bedi and Mohinder Amarnath play cricket in their heyday will still cheer for a stand in their name in their home-ground, Feroze Shah Kotla—if they can see it at all through the thick, polluting smog—even if it has come a few decades too late.

***

Nari Contractor

Tests: 31 (1955-62)

Runs: 1,611

100s/50s: 1/11

Wkts: 1

He represented Gujarat in domestic tournaments, but his home state never cared for him

Syed Mushtaq Ali

Tests: 11 (1934-52)

Runs: 612

100s/50s: 2/3

Wkts: 3

First, the Indian team’s politics impacted him. Then, the MP govt failed to ensure a museum he envisaged

V.V. Kumar

Tests: 2 (1961)

Runs: 6

100s/50s: 0/0

Wkts: 7

Selectors unjustifiably ignored this superb leg-spinner after he bagged 5/64 and 2/68 on debut vs Pakistan

Mohinder Amarnath

Tests: 69 (1969-88)

Runs: 4,378

100s/50s: 11/24

Wkts: 32

His gusty batting was often ignored by selectors and never got the recognition he deserved

Bishan singh Bedi

Tests: 67 (1967-79)

Runs: 656

100s/50s: 0/1

Wkts: 266

Considered one of the best left-arm spinners of all time, he was dropped unceremoniously after the 1979 England tour