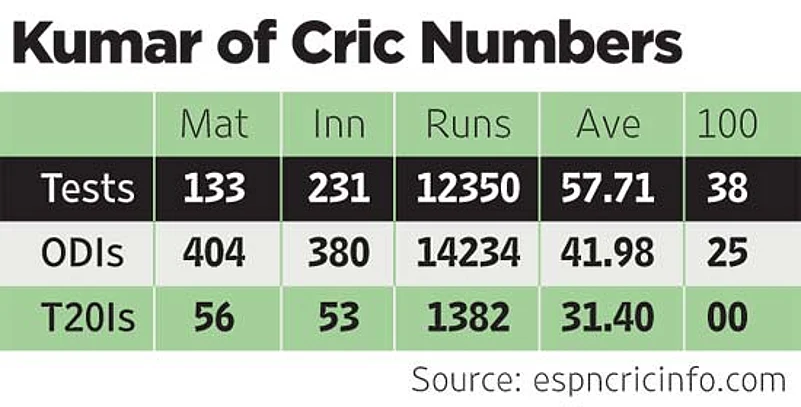

Great sportspersons inevitably leave behind a legacy. In the case of most, this is easily measured; by runs or goals scored, wicket taken, matches won.... But in the case of a few, such measures become wholly inadequate. Even if seen from the prism of only the first one, Kumar Sangakkara’s achievements are monumental. Before his farewell Test against India, he was the fifth highest run-getter in Test history (12,350), fourth highest century maker (38), and had the tenth best average (57.71). These amazing Test statistics alone would embed him deeply in the highest echelons of the sport. Add to this his wondrous exploits in limited-overs cricket and Sangakkara emerges without doubt as a once-in-a-lifetime cricketer.

But to assess him only on the basis of statistics is not just restrictive, but a travesty, for Sangakkara’s been a near-transcendental figure on the Sri Lankan psyche. He epitomised not just cricketing excellence but, through a strenuous and prolonged process of self-actualisation, gave pride, aspiration, hope, expression and direction to his small nation in finding its place in the big world.

My earliest memory of Sangakkara is from a dinner hosted by former Sri Lankan wicket-keeper Ranjith Fernando during the Asia Cup in 2004. Sangakkara and Mahela Jayawardene were the upcoming stars, having shown great promise, but yet to reach the greatness they did in the years after. Mahela was then perhaps the better-known player: of nimble footwork, highly nuanced technique and delectably stylish, a dapper artist who could use the bat like a paint brush or a magic wand. He was also the more uninhibited, easily drawn into conversation.

Sangakkara kept to himself. But his silence seemed deep then. The eyes were alert, sizing people up and assimilating everything around him. At that point, Jayawardene was clearly the bigger star, Sangakkara the side-hero. But Fernando, if I remember correctly, pointed out that a great deal more would be heard of the latter. To a lot of us, that appeared to be a fraternal feeling at play, since Sangakkara was also a wicket-keeper.

His progress till then had been modest. As a wicket-keeper he had been efficient, as a batsman more functional than heavy-duty run-maker. He was not a natural left-hander stylist like Frank Woolley or Gower, not a cussedly gritty one like Border: all told, a decent find, but hardly the kind who would rewrite record books and draw the most hardened cricket writers into purple prose. Shortly after, though, Sangakkara’s career took a trajectory that can be best described as meteoric. With every match, every month, every year, he not only got better, but hungrier for runs. He scored them everywhere, and in all formats.

With time, he surrendered wicket- keeping in Tests to concentrate on batting, and made big scores even more frequently, finally reaching a pedestal with which the sobriquet ‘great’ becomes associated. From a batting point of view, Sangakkara’s climb to such dizzying heights is fascinating. He was not a precocious youngster like Tendulkar or Lara who took his appointed place among the masters. He liked cricket, was reasonably good at it when young, but wanted to be a pilot. He was not to the manner born, so to speak. He was made into a great batsman—essentially by himself.

In his wonderful book Who Wants To Be A Batsman, former Middlesex all-rounder and now TV analyst Simon Hughes draws out Sangakkara into revealing what turned his career around. “...at 25 I had this epiphany where I suddenly realised a lot about myself,” the Sri Lankan says, in resonant words. “I realised the way I thought. I had a really good idea what my motions were like when I played well and when I played badly. I took stock of what I could do and what I couldn’t (and there was a lot of what I couldn’t do!). So I thought I’ve got to be able to improve what I can do, or hide my weaknesses for as long as I am able to, to score the runs I need.... Once I had that circularisation about myself and I wasn’t thinking about the opposition bowler or other players, my cricket started improving. Then I knew how to train, what to train, how to control my emotions in the middle, how to let my instinct take over and be a reactive batsman. That’s the best way to do it. How not to worry too much about technique.”

Telling lines for any young cricketer growing into the game on how to master oneself and conditions, but also providing an insight into the mental make-up of the man—his desires, persuasions, regimentation, philosophy of cricket, and by extension, I would imagine, also life. In the past four years—post Sri Lanka losing the World Cup final to India—Sangakkara struck a particularly rich vein of form. Astonishingly, in his last 50 Tests he has scored more runs (5,255) than anybody else in the game except Bradman (6,786).

It has been no different in one-day cricket, as his four centuries on the trot in the 2015 World Cup at age 37 show. He has used experience and ambition to provide extraordinary heft to his career at an age when most other great batsmen slow down. But in many ways, his best performance was when he delivered the mcc Spirit of Cricket Lecture at Lord’s in 2011. It was a speech derived from deep erudition on eclectic matters and magnificent in its sweep: his passion and concern for the game that had given him so much fame and reward meshed brilliantly with a deep socio-political understanding of his country that left listeners bedazzled.

This was a virtuoso performance by a maestro: not only of a sportsperson, but a statesman, a rare quality which this great game badly needs.