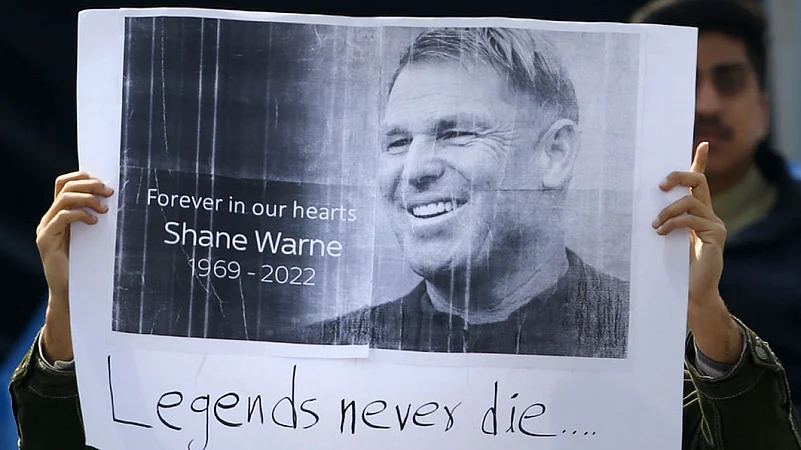

One moment he was there, large as life, perhaps larger as he often was, and the next he was gone. Unbelievably so. Unfairly so. Shane Warne lived his life in public, in the full glare of the media, but died in private on a holiday in Thailand. (More Cricket News)

Writers dug into their sack of familiar stories and cliches. Greatest. Ball of the Century. Upper body strength. Lifestyle. Liz Hurley. Sexual escapades. Rajasthan Royals. Best man never to have led Australia.

Warne’s life was an open book – but the pages didn’t tell you the whole story. As with his bowling, you always felt there was something more, something that unexplained. He loved to say that cricket found him, rather, one presumes in the manner that painting found Picasso.

Fifty-two is no age to die. Even if he lived more fully in those five decades than the average public figure lives in eight. From the time he was thrown out of the Australian Cricket Academy as a 20-year-old, Warne has never been out of the news. Yet what he achieved on the field still outweighed all the controversies he generated off it.

Cricket forces the bowler into physically challenging movements. He runs straight up to the wicket, then abruptly goes side-on putting pressure on his hip, back and shoulders, and that’s even before the arms come into play.

A leg break is a difficult art within a difficult craft. The wrist has to rotate with ball in hand and propel it towards a target some 20 yards away. Any one of a myriad tiny adjustments needed to do this can go wrong and ruin everything.

The googly causes even more difficulty with the arm having to semi-rotate, putting increased pressure on the shoulders, as the ball comes out of the back of the hand. Warne’s 708 Test wickets are testimony as much to skill as to body strength; the list of injuries is unsurprising.

A Force Of Nature

The most telling line about Warne comes from Gideon Haigh, who wrote in his magnificent study of the bowler that “what could not be taught was always there,” in Warne’s bowling.

He said he aimed not for a particular spot of the pitch but imagined rather the shot he wished the batsman to play. His strength was two-fold: the ability to give the ball a rip and spin across the bat, and the ability to suggest the big spin but bowl straight. He hardly bowled the googly, preferring instead the top spinner and a ‘slider’ which he inherited from Richie Benaud through his own coach Terry Jenner. It was like a family formula.

Warne was a force of nature, insanely gifted, perhaps a genius even. Off field he could be indisciplined and raucous. He always reminded me of Mozart in the movie Amadeus. Lesser men asked how such extravagant skills could be bestowed upon such a larrikin. Lesser men cost him a well-deserved shot at the captaincy.

It may not all have been his fault, but Warne was at the centre of some of the biggest issues of modern sport: match-fixing (he was reported for sharing information – however innocently – with a bookie in Sri Lanka), drugs (he was banned for a year after – innocently – taking a masking agent to reduce weight), sex (he was photographed in a threesome in England).

He had the aggression of a fast bowler and the self-belief that could lift an entire team. In this he was the spiritual successor of the Aussie fast bowler ‘Demon’ fast bowler Fred Spofforth, who, with England set 85 to win still believed that “This thing can be done”. And he did it, to signal the start of the Ashes legend.

The Greatest Chapter

Warne believed at all times that “This thing can be done,” whether claiming the last three wickets in 11 balls to snuff out Sri Lanka’s victory charge or seven against the West Indies a season later to finally match talent with performance after that one for 150 debut against India for whome Ravi Shastri made a double century and Sachin Tendulkar an unbeaten 148.

His first ball in England pitched nearly a couple of feet outside the leg stump and took Mike Gatting’s off stump. The look of stupefaction on Gatting’s face set the template for batsmen around the world who had been similarly done in by Warne. It is perhaps the single most written about delivery in cricket alongside the googly from Eric Hollies which cut off Don Bradman's career average at 99.94.

Nearly 15 years later, Warne bowled a similar ball to left hander Andrew Strauss at Edgbaston to which the batsman offered no shot as the ball turned and hit his leg stump. Ball of the 21st century, they called it.

And More

Warne manifestly enjoyed the game. He loved to keep everyone including the umpire involved, chatting to them on the way back to his bowling mark, occasionally calling out a one-liner to mid off and sometimes picking a fight with the batsman just to get his adrenaline going. He was a maker of events, a doer of the impossible, and millions turned up to watch him play for the promise of the unexpected.

When he led lowly Rajasthan Royals to the title in the first IPL, he had quit international cricket but his competitive spirit never left him.

In his autobiography No Spin, Warne wrote, “I have lived in the moment and ignored the consequences. This has served me both well and painfully, depending on which moment. I’ve tried to live up to the legend, or the myth in my view, which has been a mistake because I’ve let life off the field become as public as life on it.”

One over by Warne told us more about him than 400-plus pages of that autobiography did. He bowled like a millionaire and lived life the same way. In the end only memories, and Youtube videos, remain.