They are the bunch who keep running in—week in, week out—when the command comes to ‘play’. No rules govern the drawing of the schedule for the overworked Indian cricketers; nobody in the BCCI seems to be bothered about the crucial factor of fatigue. It has been thus for years. The question regarding players’ workload and the punishing schedule are either cleanly avoided or answered evasively, sometimes resulting in unintended humour. In the mid-1990s, when a BCCI secretary was asked about the reason for delay in announcing the itinerary of a particular tour, he said in all seriousness that the Board was trying to ascertain whether the next February had 28 or 29 days!

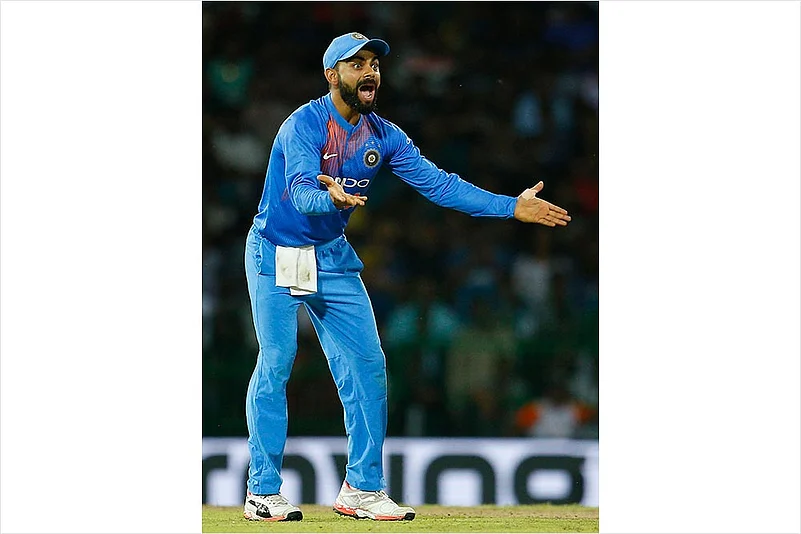

However, when captain Virat Kohli spoke his mind on virtually no breathing space between the end of the ongoing home series against Sri Lanka and the upcoming, tough tour of South Africa he was dead serious. “...Unfortunately, we get only two days before we fly to South Africa after this series gets over. So, we have no choice but be in a game situation and think of what’s coming ahead for us. Had we got a month off, ideally, we would have done a proper preparation in a camp sort of scenario,” he fumed at the pre-Test press conference when asked if he had requested for a green-top in Nagpur. It was the first time that an exasperated India captain had spoken so emphatically on the sensitive issue of match schedule.

Kohli, as if anticipating not a viscerally dominant performance in South Africa as his team has been showing at home, went on to add, “As usual, cramped for time, which I think we needed to assess in future...we don’t look at how many days we have got to prepare before we go to a particular place. And everyone starts judging players when results come after Tests, but it should be a fair game where we get to prepare the way we want to and then we are entitled to be criticised.” The cogency of his remarks can’t be disputed. The Sri Lanka tour to India ends on December 24; within a couple of days the team leaves for South Africa; the first Test starts on January 5.

That leaves almost no time for players to acclimatise to conditions considered to be one of the toughest and prepare for three Tests, six ODIs and three T20s. India are No.1 in Tests, but No. 2 South Africa could potentially displace Kohli’s team by the end of the series. Vinod Rai, head of the Supreme Court-appointed Committee of Administrators that is presently administering BCCI, has lent his ears to Kohli with ‘empathy’. Even the Lodha Committee had noted the excess workload on players and recommended that there should be a 15-day respite between a bilateral series and the start of IPL, which usually starts in April. The unrelenting BCCI, however, contested that advice. “Coming to these tours, you definitely need more time. You need to acclimatise to the conditions, for better preparation, especially when the team is doing well and your aim is to do well overseas. Two-three days between tours is hardly any preparation,” says former India Test batsman Vikram Rathour, who was a national selector for four years.

Unfortunately, the story of the last few decades is the story of the ascent of money in cricket. Now, it overrides all other considerations and is the sole determining factor for the BCCI on the number of matches that India would play in a season. This depends entirely on the kind of deal the BCCI has with the TV company that wins the rights. Once the Board commits a certain number of matches to the broadcaster, it has to deliver. When the present six-year (2012-18), Rs 3,851 crore deal with STAR India was inked in 2012, the BCCI pledged 96 matches, with an assured return of Rs 40.11 crore/match. Later, matches against Pakistan were added and the number crossed 100. So, effectively, even if the present home series against Sri Lanka hadn’t been scheduled, it wouldn’t have made much of a difference, as the BCCI has already met the promised number. In 2016-17, the BCCI organised 21 international matches at home—the maximum in a season ever—and earned well over Rs 1,000 crore. It’s clear where BCCI’s loyalties lie.

“So, what will happen in those situations is that players who would have played 15 years will burn out in 10 years. Is money bigger than the game? At the moment India is doing well. But tomorrow, god forbid, if the team performs badly, there will be no following—TV viewership will fall, automatically sponsors will come down, ultimately players will suffer. You don’t kill the hen that lays golden eggs, isn’t it?” argues Anshuman Gaekwad, a former India Test opener and national coach.

The BCCI has, rather arrogantly, been saying for some years that players who feel fatigued are free to opt out. But it gives no guarantees that on return they would automatically get their places back. “The fatigue factor will be kept in mind. No player would be forced to play. This has, in fact, been a stated policy of the BCCI. The calendar is always tight and there are so many commitments to be met,” Rajeev Shukla, chairman of the IPL governing council and senior BCCI official, tells Outlook. The ‘commitment’ he was referring to was that made to the official broadcaster. But how about a counter argument: what if the likes of Kohli, Ajinkya Rahane, K.L. Rahul, Shikhar Dhawan and Rohit Sharma seek to rest or get injured at the same time? Will the Indian team remain the same force without them?

Like Kohli, many experts feel that either a camp in India or reaching South Africa early and playing a few practice matches would have been more productive than playing Sri Lanka. Unfortunately, the BCCI doesn’t consult either players or selectors while chalking out the itinerary. Sanjay Jagdale, another former national selector, concedes that he and his co-selectors couldn’t do much about the itinerary, as it was decided beforehand. But he points out that schedules in the 1990s had much more breathing space than today’s crammed-to-the-brim calendar. “What the BCCI is doing now—the cramped tours—we didn’t have that. For example, this home series against Lanka is a purposeless tour. It was better if they had instead scheduled the Indian team’s matches against some Ranji teams. We have just toured Sri Lanka (in August-September for 5 ODIs and 1 T20),” he says.

Despite the BCCI’s back-handed offer of rest, few players opt out voluntarily. That is partly due to insecurity about their fiercely contested and hard-won places in the team and perhaps due to financial considerations. M.S. Dhoni pulling out of the 2008 Test series in Sri Lanka was a rare occasion. But Dhoni, then India’s influential ODI captain, could afford to take that step. On other occasions, Sachin Tendulkar had also opted out of some series, but he too had a larger-than-life stature. How many lesser mortals can think of that bold step?

The Indian team at the nets in Colombo in August 2017

A rare recent example is of Ajinkya Rahane, who straightaway walked into the playing XI on return from an injury-induced layoff. Kohli included him in the team for the Test against Bangladesh in February, replacing Karun Nair, who had on debut scored a triple century against England in just the previous Test. “That (insecurity) bit is true to an extent. But even senior players don’t take a voluntary break...because so much money is involved and they consider records as well,” says Jagdale.

In a perfect world, there should be a fine balance between rest and play. “Ideally, you should have two or three series, or close to—or less than—100 playing days in a year. That would give players time to recoup and recover from injuries/niggles, and to also correct faults in their game that might have cropped up,” avers Gaekwad. So what is the most acceptable solution to the perennial question of cramped scheduling and the inter-linked issue of massive revenue at stake?

The team management and the selectors need to concur that if somebody needs to rest he would also be assured of a comeback, irrespective of how his replacement performs, feels Rathour. “They are basically telling you that you are an important player for us and you need this rest. Then the players are also okay. But the players at times feel a little insecure: ‘If I ask for rest and my replacement does well, then what’?” he says. For Gaekwad, players’ input is absolutely crucial. “My suggestion is that whenever fixtures are drawn, the captain, the coach or some senior players should have a meeting with BCCI officials and tell them what they need. The fixtures can then be drawn,” opines the ex-captain of Baroda. “There should be a consistent and transparent policy of rotation and resting players. It should not shake the confidence of players,” says Jagdale.

Kohli—who has been rested for the upcoming ODIs against Lanka—has done his bit by speaking out on the back-breaking schedule. Now, the ball is in the BCCI’s court. When the TV broadcaster deal comes up for renewal at the end of March, the BCCI/CoA will have to keep Kohli’s suggestion in mind. After all, he is the hen who is laying the golden eggs right now.