In the month of July, the euphoria around the Indian cricket team’s World Cup campaign overshadowed a rare spree of achievement by the country’s less-glamorous sportspersons—boxers, shooters, wrestlers, archers and judokas. As Virat Kohli’s team broke the heart of a billion fans after losing a humdinger of a World Cup semifinal against New Zealand in England, a clutch of diehards were stretching every sinew in their bodies to win India an international medal. The returns were impressive. Overwhelming, actually. Over 31 days, across nine disciplines, India garnered an eye-popping 227 medals in various competitions, most of them overseas.

Now comes the real deal, though. In less than 12 months’ time, India’s progress as a sporting nation will be thoroughly tested at the Tokyo Olympics next July. If India can win even three per cent of its 227 medals, it would have surpassed the nation’s best tally of six medals at the 2012 London Games and five per cent would help clinch the dream “double-digit” landmark. In the Land of the Rising Sun, will it be a new dawn for Indian sports?

For the government, Tokyo is but the launching pad for bigger, long-term goals. “Excellence in Olympics is important but it’s only a small part of making an entire nation sporty in mind and body,” says former sports minister Rajyavardhan Singh Rathore, a silver medallist in shooting in the 2004 Athens Olympics. His observation is an extension of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s vision of “Jo khelta hai, woh khilta hai” (One who plays, shines) and ensuring “sports in everyone’s life”. While it will take time for India to become a sporting superpower, the signs of change are already visible.

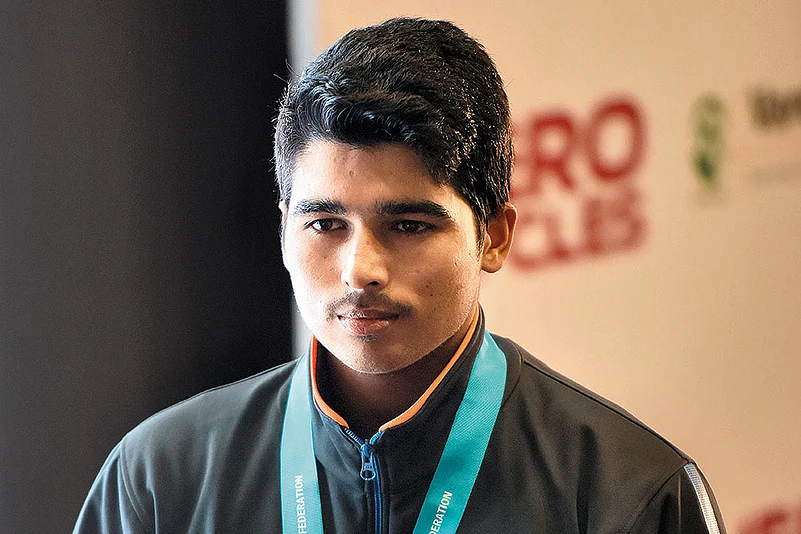

A close analysis of the 225-plus medals won this July reveals that India is awash with a new breed of athletes who are young, daring and in sync with the generation’s mood—dynamic, sharp and materialistic. While on the one hand you have boxer M.C. Mary Kom, a 36-year-old mother of three with a come-what-may desire for a second Olympic medal, and on the other we have 17-year-old pistol shooter Saurabh Chaudhary, winner of five World Cup gold and two world records, defining the flaming aspiration of the youth brigade and the huge canvas of India’s diverse representation at the Summer Games.

DATA SET IN GOLD

An in-depth study by technology and data company Gracenote (called Infostrada Sports before) says India could win 14 medals—one gold, five silver and eight bronze—in Tokyo and finish 21st in the final medal standings. With two medals—a silver and bronze—in Rio 2016, India finished 67th. In London 2012, India (2 silver and 4 bronze) were 57th. Gracenote’s virtual medal table forecast a year before the Tokyo Games (from July 24 to August 9, 2020) is a statistical model based on individual and team results in previous Olympic Games, recent world championships and World Cups. The data is updated thrice in the run-up to the Games—before 100 days, 30 days and one day.

These prediction models take into account the disciplines that a country is strongest in—Australia, for example, can win most of their medals from swimming or the US from track events and India presumably from shooting or wrestling—but their accuracy can be as high as 82 per cent. At least five data companies forecast with 80 percent-plus precision the medal hauls of the five top nations at Rio 2016. Both Gracenote and BEST Sports, another data company with an average of 80 per cent accuracy rate, predict that the US and China will finish one-two in Tokyo. There is only a difference of eight medals between the predicted haul of the top two. However, there is a catch. While there is a great degree of uniformity in the data projections of these companies in forecasting the top 10 countries, the probability fluctuates by astonishing margins when it comes to nations not expected to finish in the top 20. Against Gracenote’s 14, BEST Sports gives only five medals (2 silver + 3 bronze) to India for a 63rd finish in Tokyo.

If BEST’s prediction comes true in Tokyo, then it’s bad news for the Indian Olympic Association (IOA). According to its president Narinder Batra, if India doesn’t win medals “at least in double digits”, then the country’s bid to host the 2032 Summer Games and the 2026 Youth Olympics will get a severe jolt. Mumbai, the city of International Olympic Committee member Nita Ambani, has expressed its interest to host these Games. “If we don’t win medals in double digits, there will be very little public interest and government support to host these big-ticket events,” he adds.

SLOW AND STEADY

But the Indian government is in no hurry for medals in Tokyo. After upgrading the Khelo India School Games of 2018 to Khelo India Youth Games in 2019, the sports ministry raced to integrate the country’s youth through sports. This January, Pune’s Balewadi complex created an Olympics-like atmosphere as over 400 gold medals in 18 disciplines were up for grabs. Maharashtra, Haryana and Delhi finished 1-2-3. The seriousness was palpable and the visibility eye-catching, considering the live TV feed.

“At least the government is taking some initiative to raise awareness among youths but it’s not enough. Sports is a state subject and since it is not a vote-catching mechanism, most states except perhaps Odisha are least bothered about development and infrastructure,” says Batra, adding that Punjab and Haryana had “no interest” in spite of the fact that several international sportspersons belong to these states.

Rathore, who handled the sports ministry for about 17 months, was successful in putting a few systems in place. It wasn’t easy to activate a sarkari system to suddenly manage sportspersons and events in a professional way. But the 2019 Khelo India Youth Games saw a definite transformation that hinted at a changing mindset among a clutch of hitherto laidback officials in the government sports system. “When I was given the ministry, the Prime Minister told me that not every child can go to the Olympics but the government can set up a platform where children are exposed to an atmosphere that will whet their appetite for excellence and more importantly, inspire them to make sports a way of life,” says Rathore. “Not in 2020, the first sign of the efforts we are making now will reflect in the 2024 and 2028 Olympics,” he adds.

At least two foreign coaches involved with the preparation of Indian wrestlers and boxers for the Tokyo Games also feel the country has a better chance to excel in the 2024 Games in Paris and peak four years later at Los Angeles. Their evaluation comes from current results in international tournaments and the age-group of athletes. Wrestling, boxing and shooting are particularly in spotlight. Interestingly, the probability of women outshining men is very high. Tokyo will be the first Summer Games in which fewer than 50% of medal events will be open to men only. The proportion of women’s events rises for the 10th Olympic Games in succession, according to Gracenote.

While 24-year-old Vinesh Phogat remains a big medal hope in Tokyo by virtue of her sheer experience and form, India’s medal prospects for 2024 lie in the under-15 group that is technically stronger than the older group. Forty-year-old American Andrew Cook, who trains the women’s wrestling squad, is certain 2024 will be a watershed in India’s wrestling history at the Olympics. But only if the Wrestling Federation of India respects a fair and scientific selection process.

Indian boxing’s high performance director Santiago Neiva, an Argentinean who lived all his life in Sweden, has a similar view. With India expected to put up a boxer in all eight men’s weight division and five women’s categories, the largest ever boxing contingent could walk out at Tokyo. “Olympics are special and many world champions have failed to win at these Games. Vijender Singh (bronze in 2008 Beijing) and Mary Kom (bronze in London 2012) have shown nothing is impossible and in Tokyo, we will do something great,” says Santiago. “But 2024 will see a major breakthrough for Indian boxing,” he adds.

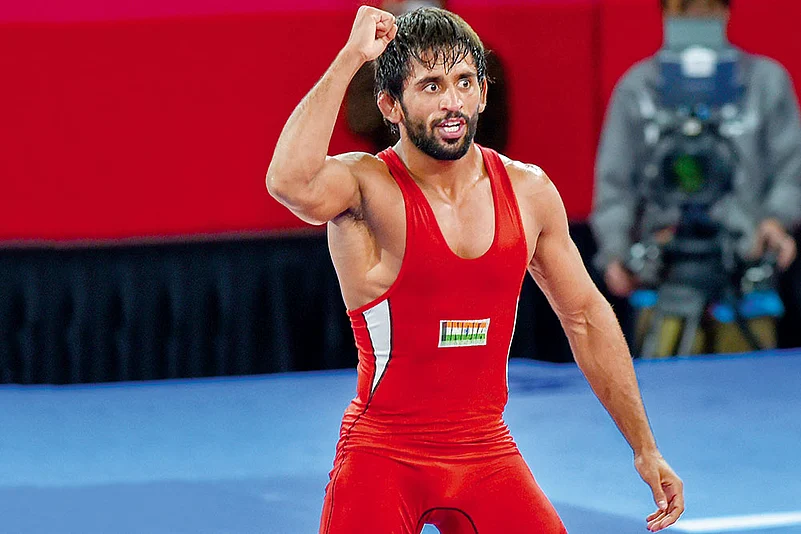

India owes a lot for this sporting turnaround to the government’s Target Olympic Podium Scheme (TOPS), launched in September 2014 but restructured last year. Under this scheme, managed by top sports managers, elite athletes are being given support, security and personal attention that was either missing or arbitrarily managed for years. Stringently reviewed, without bias and malice, TOPS is a symbol of the accountability that Indian sport needed. “My personal interaction with the TOPS managers has been great. They know exactly what we need. The individual support from the government has been amazing and I hope it continues,” says ace shuttler P.V. Sindhu. Top wrestler Bajrang Punia credits TOPS for the transformation in his career. “From the mud pits to the mat, from the best coaches to the right sparring partner, it’s TOPS that has given me the support I needed,” he adds.

Currently, the scheme supports 76 elite athletes across 11 sporting disciplines—able-bodied and para included. It works under a CEO and has representatives from the Indian Olympic Association and National Sports Federations. “I have reviewed the support being extended by the government to our elite athletes and I think we are pretty much on the right track,” says Kiren Rijiju, the man who replaced Rathore.

While there is no fixed budget, after the fresh list of athletes expected to be at Tokyo were approved in November 2018, approximately Rs 4 crore has been spent to support the players. An out-of-pocket allowance of Rs 50,000 a month is given to athletes as an incentive. “It was embarrassing when our athletes were lighting stoves in their hotel rooms to cook noodles and often setting off the fire alarm after burning expensive carpets,” Rathore remembers. “TOPS has set an example for the world to follow. I have been training in Ukraine for two years and the local athletes are amazed that our government is sponsoring everything that I need. Personally, it’s been a great help and the fact that pursuing sports in no more a financial burden makes me focus better,” says Sharad Kumar, a former world No. 1 para high-jumper who won the 2018 Asian Games gold in Jakarta.

In Tokyo, athletes will be at home in India House where they will get the food of their choice. But it’s still a long road to Tokyo and India still needs to qualify in boxing, wrestling, badminton, track and field, and hockey—disciplines that have the highest medal prospects. The shooters got a headstart. Of the 158 distributed so far, seven have grabbed ‘quota’ places through qualification processes. With a year to go, the shooters could surpass the Rio 2016 record of 13 spots. But let’s not forget that in Rio, we drew a blank in shooting—a sport that gave India its lone individual Olympic gold at Beijing 2008.

Starting August-September 2019, the quest to board the plane to Narita will begin. The likes of Hima Das, Vinesh Phogat, Sakshi Malik, Bajrang, Mary Kom, Shiva Thapa and Sindhu et al will be under the spotlight. Except for some personal glory, those 227 international medals will count for nothing if they don’t make the Olympic cut.

***

Bajrang Punia, Wrestling (65kg freestyle)

- Personal Best: first (current world ranking), 2008 CWG gold medal, 2018 World Championships silver medal

Amit Panghal, Boxing (49 kg)

- Personal Best: sixth (current world ranking), 2019 Asian Championships gold medal

PV Sindhu, Badminton

- Personal Best: fifth (current world ranking), 2016 Rio Olympics silver medal

Vinesh Phogat, Wrestling (53kg freestyle)

- Personal Best: sixth (53kg category current world ranking), 2018 CWG gold medal

Saurabh Chaudhary, Shooting (10m air pistol)

- Personal Best: second (current world ranking), 2019 ISSF New Delhi World Cup gold medal, 246.3 (personal best final score in 2019 World Cup)

- Olympic Record: 202.5 final score (Hoang Xuan Vinh, 2016 Olympics)

Mary Kom, Boxing (51kg)

- Personal Best: first (current world ranking), 2012 Olympics bronze (flyweight)

Manu Bhaker, Shooting (10m air pistol)

- Personal Best: ninth (current world ranking), 2019 ISSF New Delhi World Cup gold medal, 242.5 (personal best final score in 2018 Junior World Cup)

- Olympic Record: 199.4 final score (Zhang Mengxue, 2016 Olympics)

Apurvi Chandela, Shooting (10m air rifle)

- Personal Best: first (current world ranking), 2019 World Cup gold medal, 206.9 (personal best final score in 2015 World Cup final)

- Olympic Record: 208.0 final score (Virginia Thrasher, 2016 Olympics)

Mirabai Chanu, Weightlifting (48kg)

- Personal Best: second (current world ranking), 2017 World Championships gold, 199kg (personal best)

- Olympic Record: 97kg (snatch) + 117kg (clean and jerk) = 212kg (Chen Xiexia, 2008 Olympics)

Anjum Moudgil, Shooting (10m air rifle)

- Personal Best: second (current world ranking), 2019 World Championships silver medal, 248.4 (personal best final score in 2018 World Championships

- Olympic Record: 208.0 final score (Virginia Thrasher, 2016 Olympics)