In March 2015, Balbir Singh Senior was given a Lifetime Achievement Award by the Indian hockey federation (Hockey India). Interestingly, the award was named after Dhyan Chand, a man with whom he shares the pedestal in debates on India’s greatest hockey player ever. Balbir Singh died on May 20 at the age of 96. While opinion remains divided about ‘the greatest’, Dhyan Chand and Balbir share a common story—that of being denied and ignored.

While Sachin Tendulkar getting the Bharat Ratna in February 2014, within three months of retiring from Test cricket, gained ready acceptance, the government’s mulish overlooking of the two legends who, with three Olympic gold medals each spanned the glory years of the national sport, remains one of the greatest mysteries of Indian sport. “Maybe they did not have the right connections at the government level,” says 1975 World Cup-winning Indian hockey captain Ajit Pal Singh. Dhyan Chand won three (1928, 1932, 1936) successive Olympic gold medals before Independence and Balbir was part of another three straight gold-winning teams in the London (1948), Helsinki (1952) and Melbourne (1956) Olympic Games.

Historian Ramachandra Guha explains the lack of peripheral vision of the men in charge of sports in India. “If we didn’t win the cricket World Cup in 1983, hockey would still have been our favourite sport. Dhyan Chand has not got his due because he played hockey; Ramanathan Krishnan, who reached the Wimbledon semis twice, didn’t get his due because he played tennis; world champion Wilson Jones didn’t get his due because he was in billiards and five-time world champion Viswanathan Anand hasn’t got his due because he plays chess. All non-cricketing sporting greats don’t get their dues in India and Balbir was one among them. We are obsessed with cricket, we pamper them, give them too much value and forget other legends,” says Guha, adding that Anand deserved the Bharat Ratna more than Tendulkar.

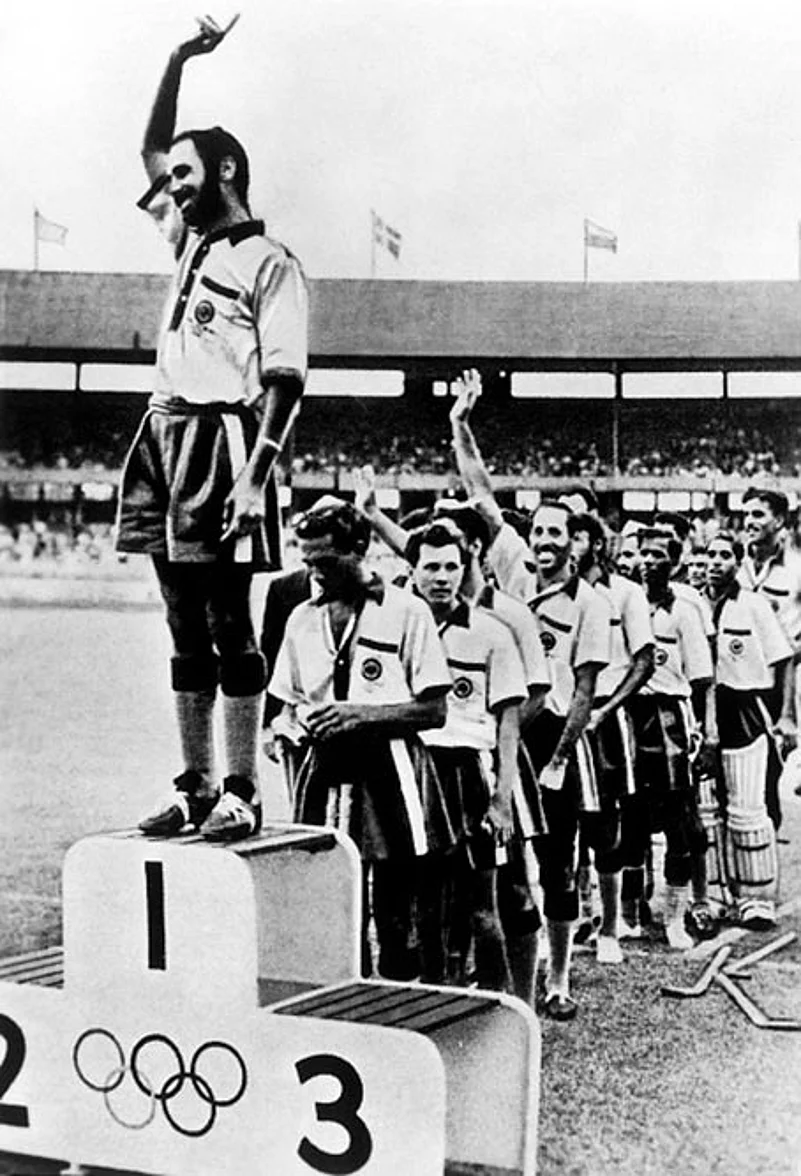

Balbir Singh leads the Indian team at the medal ceremony in the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne

Having grown up on stories of Balbir and his two inseparable partners in the forward line—Udham Singh and Raghubir Singh Bhola—Guha had a chance meeting with Balbir Senior in Vancouver in 2005. “I was there for a talk on Gandhi and Balbir showed up. I wanted to touch his feet; he stepped back and was happy to shake hands. Sikhs believe in equality and that was the measure of this man in his 80s,” recalls Guha. “Balbir and Dhyan Chand were easily as great as Kapil Dev and Tendulkar or Dhoni and Kohli, may be greater. They should have got the Bharat Ratna before Tendulkar.”

And though they live on in countless memories, lack of government recognition has left both families bitter.

Professor Swaran Singh, who wrote Balbir’s biography in Punjabi, points out that the International Olympic Association had acknowledged Balbir’s contribution during the 2012 London Olympics. “He was among the 16 chosen sportspersons to represent the history of the modern Games. Balbir is the only Indian to be on such an elite panel that had Jessie Owens, among others. Even Dhyan Chand was not there. The IOC made him an Olympic ‘ratna’, but it is unfortunate that the Indian government still hasn’t.”

Prof Singh says Balbir, who saw Dhyan Chand as his guru, never yearned for anything. He would never express his frustration, but his family wanted him to get the Bharat Ratna. In 2015, when Balbir was over 90, Swaran Singh published his biography Golden Goal. Balbir himself had earlier written two books—Golden Hat Trick (1977), his autobiography, and Golden Yardstick (2008), on coaching. “Over the past two years, Balbir was in an out of hospital. He said he was living in extra time and the moment the golden goal would be scored, he would be gone forever,” says Prof Singh.

Balbir after scoring in the 1948 London Olympics

Balbir’s close associates always saw him as a more deserving candidate than Dhyan Chand to win India’s top civilian honour. “Dhyan Chand played at a time when hockey was not even a competitive sport. He played for British India and the Union Jack would go up at medal ceremonies. There is no denying Dhayan Chand’s calibre as a player but Balbir’s goals came against teams that had quality players. Also, he played for independent India,” argues Prof Singh.

Indeed, the debate about their competitive merit is an endless one. Dhyan Chand had mesmerising stickwork—the one undisputed ‘wizard’ in hockey history, one whose feats in the 1936 Berlin Olympics (India beat Germany 8-1 in the final) deflated the Nazi theory of ‘Aryan superiority’ as much as did Jesse Owens’s dominance in athletics. Balbir, with miraculous, unequalled situational awareness on a hockey field, was a great centre forward (‘the greatest’, according to experts) and goal-scorer whose rapier passes wreaked havoc amongst opposition defences. Equally unparalleled was his marshalling of the team on the field.

The issue of the Bharat Ratna has justifiably caused heartburn in Dhyan Chand’s family. “You will not understand the pain it creates every time I am asked this. It seems I am complaining,” says the maestro’s son Ashok Kumar, who played in three World Cups and the Munich Olympics in 1972. To “dispose of a three-time Olympic champion like Balbir Singh with just a Padma Shri is gross injustice,” he says, “when sportspersons get major awards by winning an Asian-level medal or an Olympic bronze. The qualifying standards have gone down. Why deny Balbir Singh of at least a Padma Bhushan?”

Receiving the Dhyan Chand Lifetime Achievement Award in 2014

Dhyan Chand has the National Stadium in Delhi named after him. The national sports day is also dedicated to him, and a postage stamp was released in his honour. “From outside, it looks all very good, but do people know that Dhyan Chand was fighting a battle to keep his family alive? For 50 years, he was away from his family, following orders and playing hockey. But the returns were poor. He scolded us for playing hockey, saying the game will never give us a future,” says Ashok Kumar.

Saying his ‘upright’ father was the quintessential army man, Ashok Kumar said Dhyan Chand would never ‘beg’ for anything. In 1976-77, Ashok Kumar had drafted an application for a gas agency but Dhyan Chand refused to sign, saying, “I played whenever I was asked. Now it’s the turn of the government to give me shelter, food, water and electricity.” Dhyan Chand died in Jhansi in 1979.

To say that both Balbir and Dhyan Chand have felt ignored by the authorities is probably an understatement. Two former national captains, Gurbux Singh and Pargat Singh, feel that to single out one player as the ‘greatest’ is always a fraught exercise. Pargat says Dhyan Chand became famous and popular because he was the “talk of the system” and given the status of a celebrity, while Balbir was barely discussed. “To the hockey community, both Dhyan Chand and Balbir are equally important. You can’t compare them.”

Part of the 1964 gold-winning Tokyo Olympics team and captain of the 1968 Mexico squad, Gurbux Singh, now 84, agrees with Pargat. As one who played against both Dhyan Chand and Balbir, Gurbux says no player is complete without the support of his teammates. “For us, not just Balbir, but K.D. Singh Babu, Udham Singh, Keshav Datt and Leslie Claudius were heroes. To say someone is the greatest in a team sport is being foolish. Balbir was a great scorer for sure, but without Udham or Bhola or KD alongside him, he would be nothing,” he explains.

Men like Dhyan Chand and Balbir Singh Senior—proud men who served their country’s banner with excellence, heedless of material gain—will continue to leave sports fans in awe of their achievements. Discussing these two hockey legends in the light of the Bharat Ratna can only be part of a movement to restore Indian hockey to the apex of the nation’s sporting consciousness.