IPL Season 12 is hitting its final, flood-lit crescendo as we write this. The fanfare, the cheers and heartbreaks, the breathless excitement, the sometimes seemingly impossible skills on display out on the striated green…all of it peaks in Sunday’s final. But this is not about that, not about those 22 yards, and who the last man standing will be. This is about another kind of pitch, millions of them in fact…they roll out in a virtual space, on your smartphone screen. It’s called Dream11: you would have seen the ads if you’ve been watching the IPL, they’re all over the prime slots. Dream11 comes with its own fanfare, its wins and crushing losses, its thrills—and, apparently, skills. But then, so does poker. It’s just that those ‘skills’ are akin to those involved in horse-racing—not those of the jockey on top of the marvellous animal streaking across the tracks, but the one chomping on the cigar nervously in the stands, making what he thinks is an informed guess, but often wiping his brow in frustration after betting on the wrong horse. For, the one essential ingredient that greases this parallel stockmarket of seemingly easy pickings is…you guessed it! It’s Luck, a lady with a more enigmatic smile than Mona Lisa’s. Even if you were a gambling man, you wouldn’t bet on what that smile means.

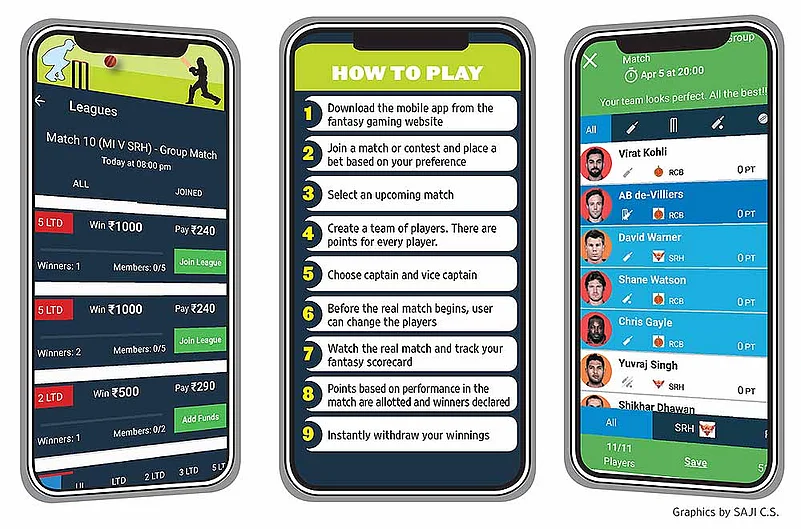

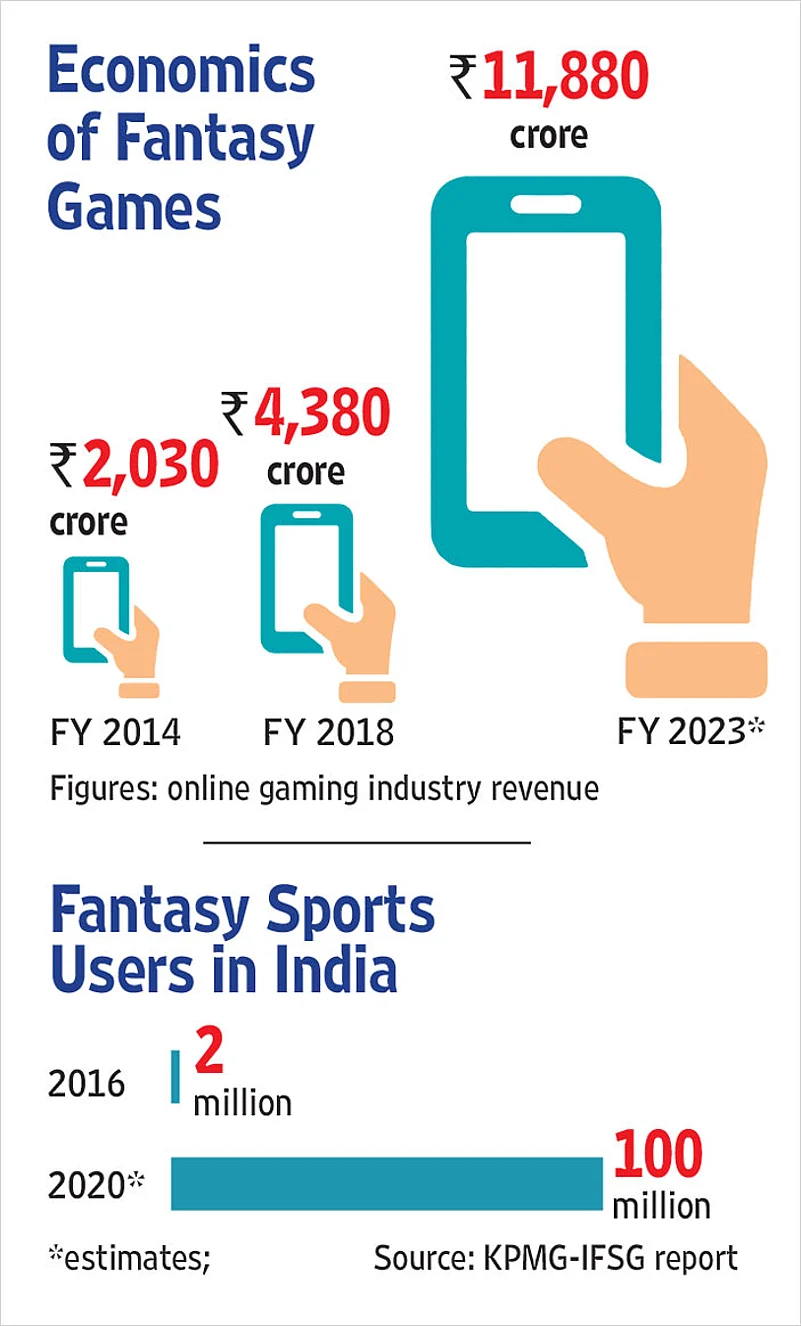

Before we come to the greys, first the black and white. We’re talking about fantasy cricket—part of what they call online fantasy sports gaming (OFSG). There’s no cricket, really. Sports fans simply pay to enter the game, and click buttons to select their own team, made up of real-life players, for upcoming matches . These virtual teams garner points based on the actual performance of players in the real-life match: winners (and losers) are determined thus. They win and lose cash. The industry calls it “skill-based” online sports gaming, and it’s widely played across cricket, football, kabaddi, basketball et al. In India, with mobile data going cheaper than sixes in a T20 match, fantasy sports is projected to go up from the 2 million users we had in 2016 to as many as 100 million in 2020—that’s almost the population of France and England put together. Dream11 is the biggest daddy in fantasy cricket in India. It’s actually an official partner of the BCCI for its hottest franchise, IPL 2019. Dream11 officials stand around in the after-match ceremonies. The ICC is on board too. M.S. Dhoni is a brand ambassador. There’s a large legitimising force here, a network of tie-ups.

Now, the shadows moving across the poker face. The fundamental question: is this a form of gambling that claims to be kosher, while bypassing the fact that gambling is cast in varying shades of illegality in India? (This can be asked, at the outset, without a value judgement on the question of whether gambling and betting should be legalised.)

Gitanjali Patil and family, fantasy cricket enthusiasts.

Look at the patterns: the games are available in both free and paid versions. But curiously, they can’t be downloaded from Google Play Store—you have to go through website links. When Outlook contacted Google, it sent a link that stated “gambling apps are permitted” only in the UK, Ireland and France currently. “For all other locations, we don’t allow content or services that facilitate online gambling, including, but not limited to, online casinos, sports betting and lotteries, and games of skill that offer prizes of cash or other value.” Google refused to comment on individual apps as per their policy. A senior Google official, on condition of anonymity, told Outlook, “In India, fantasy gaming is still a grey area with no legal standing or backing. As per worldwide debates and our understanding, anything that involves the risk of winning and losing money is a kind of gambling, so we are just adopting a defensive approach.”

Google is not alone in its attitude of avoidance. There are five states in India that are no-go areas for fantasy sports platforms: Odisha, Telangana, Assam, Nagaland and Sikkim. When you play fantasy games on your phone, you have to certify you’re not a resident of these states. In Assam, Odisha and Telangana, skill-based fantasy games can be played only on free subscription, not paid, while in Nagaland and Sikkim, a company needs to obtain a licence to host paid gaming. The terms of Sikkim’s licence specify that online games may only be offered within the physical premises of gaming parlours through intranet gaming terminals. Also, a company has to put up an online gaming levy of Rs 50 crore, or 10 per cent of the gross gaming yield, whichever is higher.

The defensive approach of Google and these five states is courtesy an Indian law that’s over a century and a half old: the Public Gambling Act, 1867, which prohibits the running of a public gambling house, and even visiting one. The subtle distinction it makes is between a “game of skill” and a “game of chance”. As Rajat Prakash, managing partner in law firm Athena Legal, puts it: “The test is to determine what dominates/preponderates, whether skill or chance?” This naturally creates room for interpretation—the Supreme Court has, for instance, come in on the question of whether rummy is pure chance (it said it was not). Gambling, at the same time, is a state subject and many state governments have adopted the model act with their own interpretations. All but a handful, like Goa, impose restrictions. However, new modes like fantasy gaming are stretching the interpretive limits of the old law, seeming to blithely bypass it without scrutiny, while new cyber laws skirt around the question of gambling too.

And so, an ancillary e-industry is booming along with the game it’s parasitic upon: it’s like an explosion of mini-IPLs unspooling in countless living rooms of India, in front of TV sets.

Gitanjali Patil, who got married last year, didn’t know what Dream11 was until her brother-in-law dropped her “a link on WhatsApp and told me how to play it”. Gitanjali, 30, vice president of a real estate firm in Mumbai, isn’t the only one in the Patil family who has taken a fancy for fantasy cricket. Her father-in-law (58, a former businessman), brother-in-law (works in a real estate firm) and some cousins overseas created a WhatsApp group in March to discuss all the fun and matches. All die-hard Dream11 fans, they start their conversation early in the day to decide the cricketers they want in their team. “Some 7-8 players are the same for us, we discuss and share, the rest we decide individually,” says Gitanjali. The Patils sit together around 7.30 pm—half-an-hour before the match—to log on to the game and make last-minute changes in their teams. “Dream11 has introduced this interesting, user-friendly concept where players can be changed at the last moment so that if they are dropped from the match, they can be dropped by users from their teams too and we don’t lose points or money,” says Gitanjali. (Earlier, one could do so only till one hour before the match.)

Fairly Legal?

While more and more users indulge themselves, it’s important for both the Centre and state governments to clear their stand on fantasy sports that involve money as the industry is growing bigger and bigger. According to an IFSG-KPMG report (IFSG being the industry body for online gaming), India’s e-gaming market has seen tremendous growth of late, driven in part by the surge in digital usage. Revenues have nearly doubled over a period of four years, reaching a whopping Rs 4,380 crore in FY2018. At the expected compound annual growth rate of 22.1 per cent, that would touch Rs 11,900 crore by 2023. That kind of money can also mean big revenue for governments—and that has always been an argument for legalising betting, which otherwise carries on unregulated in shady satta bazaars, with all the attendant social problems. But nothing this big should go without the clearest sanction in terms of the legal position. And how is this qualitatively different from gambling, if at all, in the first place? And what could be the pitfalls?

Well, as of now, the industry is riding high on a 2017 judgment. In the Varun Gumber vs Dream11 case (see profile), the Punjab and Haryana High Court went through the entire Dream11 format, and ruled that it does not constitute betting and gambling—rather, it said, it was a game of skill and a business, which is protected under the Constitution of India. The Supreme Court too dismissed the petition, agreeing with the high court’s view. Lawyer Prashant Reddy, however, says the SC has not really ruled on the issue: it was a summary dismissal. So it’s not clear if other high courts are going to consider themselves bound by the Punjab and Haryana HC’s decision. That may be why these companies are not yet moving into Assam, Telangana and Odisha.

Namita Viswanath, partner, IndusLaw, concedes “the Supreme Court has not passed a judgment and hence the legal position remains inconclusive”, but believes it’s “a step in a positive direction to treat fantasy games as games of skill rather than chance”. Success in these were deemed to “depend on a substantial degree of skill, superior knowledge, judgement and discretion of the person, as opposed to mere chance”, she says. However, she points to an interesting potential consequence: “The question that then arises is, if live sports betting, traditionally seen as gambling, can also be categorised as games of skill as they do not involve skills substantially different from those required for fantasy sports games.” Some clarity may come soon, she says, for the Law Commission has “recently proposed enacting a new central law to cover online gambling and betting”.

Athena Legal’s Rajat Prakash says the high court decision was significant as it set a precedent in the context of online games. “Previously, courts had taken a view that online games and video games could be manipulated from outside, hence the degree of chance would increase. Some courts had also taken a view that any game with stakes is gambling,” he says. But he has a caveat for developers and entrepreneurs: “Whether a specific game is a game of skill or chance depends in each case on the nature of that game and skills required for playing it. This makes the law uncertain, as the likelihood of any future online gaming venture being termed gambling or sports betting cannot be ruled out. The decision in the Dream11 case remains unique to the facts of Dream11 only. Each case will require its own factual analysis.”

Reddy points to the most crucial thing to be considered before adjudicating on anything that resembles betting or gambling. “The problem we should all be prepared for is the very real possibility of gambling addiction. Legislative clarity would be helpful for investors, but we also need to keep in mind the social cost of allowing such ventures,” he says.

The Players

Interestingly, the ones who agree with that last bit about addiction, through direct testimony or otherwise, are those who play themselves. Says Nitesh Yadav, who has won over Rs 10 lakh through fantasy sports: “I started it as fun to earn extra bucks in college. For a year, I’ve been playing it regularly as a secondary source of income. It’s becoming an addiction. People should be careful.” Luck does matter, adds Yadav (see profile).

Ask Gitanjali if she thinks it’s betting, and her answer is no. “It depends on how well you know the players, their performance and how they have been playing. I’m not only hooked on cricket, but also play fantasy kabaddi, which is amazing,” she adds. She has invested lakhs over a year and lost some too, though she thinks her profits outweigh her losses on Dream11. “My father in-law plays games of around Rs 1,000 using three mobiles, while I prefer small leagues with two or three people as winning amounts are high and chances of losing low. I prefer to play bets of around Rs 5,000. I’m confident of my skill and it’s so much fun.”

Miles away from Mumbai, in dusty Delhi-NCR, the same fervour plays out. A gang of four friends, after finishing their jobs in Gurgaon, gather at a cafe or home every day to enjoy their Dream11 matches along with IPL. Ankit, a retail manager, says: “I play it occasionally in small leagues with just 10 players or less. That’s more interesting and full of thrill. Grand leagues with the number of players in thousands, lakhs or crores, where people prefer to be conservative, are for beginners.” It’s “fanmania” out there, Ankit confirms. Several of his friends, both girls and boys, play with paid subscriptions.

Of course, you start losing, and it’s no longer such fun. Says Nikhil (name changed), who lost around Rs 1 lakh in the last three months, “It starts as fun and then you become more and more confident, placing bigger bets. And then you get a setback when you start losing. I required clinical help to get out of this habit after my family came to know.” He questions the business model—why is the government not regulating this form of “sophisticated gambling”, he wants to know.

We profiled the Mumbai-Dilli types. But trouble is, according to the IFSG-KPMG report, users from the top 7-8 Indian cities were found to be playing less frequently than those from the smaller cities. Nearly 85 per cent big city respondents played 1-3 times a week, and some 70 per cent respondents from smaller cities played over four times a week. These are players from Tier II, III and IV cities like Lucknow, Kanpur, Amritsar, Chandigarh, Jaipur, Kota, Rajkot, Tiruppur and Dehradun. According to industry lobby group IFSG (Indian Federation of Sports Gaming), their initial 10 million users were predominantly from Tier I cities, but now 50 per cent of their traffic comes from Tier II and III cities. Note the presence there of education hubs like Kota and Dehradun, implying the big numbers of students engaged in this, users who are anyway financially stressed, and you begin to understand the scale of the problem. And with star cricketers becoming brand ambassadors—Dhoni for Dream11, Suresh Raina for Fantain, Virat Kohli for Mobile Premier League—people often don’t understand that this is a legally sensitive area.

The Gamers

The gaming apps come in two segments—Freemium (free and paid) and only-paid models. These paid versions have entry fees ranging from as low as Rs 10 to as high as Rs 10,000 and more. Till 2018, there were around 70 fantasy sports operators in India, according to IFSG. Besides Dream11, these include Fantain, Dotball, Halaplay, MyTeam11, 11Wickets, Starpick, to name a few. Anand Ramachandran, co-founder and CEO of the BookMyShow-backed Fantain, says his is a ‘freemium’ model, where fans can play free fantasy cricket for any amount of time before converting to paid fantasy. Generally around 10 per cent of the fans who play free move on to paid: it’s like a threshold drug. While the paid form is the major source of revenue for Fantain, “we do not attempt to convert every fan to a paid fantasy gamer. Users play fantasy sports for various reasons and we want to serve all of them,” says Ramachandran. The platform has 6 lakh users and has seen an eight-fold increase in volumes between IPL 2018 and IPL 2019.

(clockwise from top left) M.S. Dhoni, Sunny Leone, Suresh Raina and Virat Kohli, in ads endorsing various fantasy sports platforms

Cricket is by far the most popular fantasy sport—with the World Cup imminent, expect no abatement—followed closely by kabaddi and football. Fantasy platforms say Dream11 laid the groundwork, which has made marketing efforts for startups and new platforms very easy. “We don’t have to take extra pains to create awareness,” says Hridhay Murlidharan, co-founder of fantasy cricket platform Dotball. A purely paid subscription model, Dotball has 2 lakh subscribers and distributed Rs 1.5 crore as winning amount in last eight months. Adds Murlidharan: “We categorise customers into three segments: students who play to earn pocket money, casual players who play occasionally, and hardcore fantasy users.”

The fans pay an entry fee to participate and the operators take a fee: the balance is given back as winnings. The rules by which winners are determined are clearly laid out and there for all to see. Even before joining any contest, fans can see the number of participants, the quantum of winnings, etc. Operators have gone to great lengths to ensure every fan has an equal opportunity to win, provided he/she understands the game well. They also provide a lot of real-time statistics to help fans select the right team.

The apps take great pains to understand fantasy fan behaviour. Says Ramachandran of Fantain, “A one-size-fits-all approach is unlikely to work in the long term and hence we invest heavily on fan analytics. Based on our analysis, we have launched multi-match fantasy to target the serious cricket fan, who may not find the single-match fantasy challenging enough.”

Sarkar, Board and GST!

The question whether fantasy sports are legal reached Parliament this year. In February 2019, MoS (Finance) Pon Radhakrishnan parried a series of questions from TRS MP A.P. Jithender Reddy, saying betting and gambling came under “Entry 34 of List II of the Seventh Schedule” and state governments were competent to enact laws. But the more immediate question relates to the BCCI and how it invested so deep in Dream11 when the legal position is still not clear. Vinod Rai, chairman of the BCCI’s Committee of Administrators (CoA), didn’t respond to calls, but his co-member Ravinder Thodge told Outlook that he was not involved in the Dream11 sponsorship as he joined the committee only recently. However, a senior BCCI functionary explained how IPL sponsorship works. “The BCCI’s IPL Operations team gives sponsorship suggestions to the CoA and the CEO [Rahul Johri]. But about 90 per cent of the work is done by the IPL Operations team. Obviously, the BCCI office-bearers are also involved in all this,” he told Outlook.

But Kishore Rungta, former BCCI treasurer (1998-2003), casts it in an interesting frame. “A lot has changed in the past few years. I.S. Bindra, former BCCI president, used to say the government should make betting legal, while Jagmohan Dalmiya, who became president a few years later, had the opposite view. All this we used to discuss privately, not at any BCCI forum,” says the 67-year-old Rungta.

Dream11 office, Mumbai

“But even if you make betting legal, it won’t have any impact today as 18 per cent GST will be applied, like in horse-racing!” Rungta adds. “My belief is that whoever gambles in horse-racing will not pay GST because the bhaav ranges from 60 paise to 80 paise. If you put in Rs 100 and you have to pay Rs 118 GST, no one can afford it. What will he save? Gambling would happen under the table. In places like London, taxes on horse-racing betting is much lesser.” Sure enough, in February, the Turf Authorities of India (TAI), the apex body of the six racing clubs in India, made a representation to Union minister Piyush Goyal with a request to reduce the heavy GST charged on bets by race clubs and bookmakers. This happened after the Mumbai police arrested racecourse bookmakers and lottery parlour owners for alleged GST evasion in December 2018.

Former BCCI Anti-Corruption Unit chief Neeraj Kumar, a former Delhi Police commissioner, has a related warning. “It’s so difficult to deal with even regular betting as a criminal offence,” he says. “The Gambling Act too is such a weak act…even if you book someone under it, the fine is just Rs 400 or Rs 500. What difference does that make to the offender? So we charge them under the IPC’s section 420, criminal misappropriation etc. Now, with fantasy sports platforms, it’s very difficult to say if the Gambling Act can be enforced here. But they must surely be raking in crores and crores with every game. So many people are paying money to play, and only a few are getting the prize…they must be gulping down the rest of the money. You don’t need to maintain an office or a huge infrastructure, yet you earn crores in one sweep.”

Kumar adds that no case has succeeded till date under the Gambling Act, “whether it was the Hansie Cronje scandal, or the Mohammed Azharuddin case, or even Sreesanth’s case, except for disciplinary action”. “The laws are so weak that, for example, terms like ‘fixing’ and ‘spot-fixing’ are not even there in the laws,” he says.

Dotball’s Murlidharan clarifies that single contest winnings above Rs 10,000 on any gaming platform are taxable and the companies have been filing their returns. Fantasy sports platforms charge a 31.2 per cent tax on earnings of players above Rs 10,000. There is no tax for lesser amounts, and the money left after the winning amount is disbursed is the company’s income. “The industry’s biggest concern is there’s no clarity on whether the 18 per cent GST is on service fee or entry fee. If it’s entry fee, gaming platforms will be left with zero margins. It’s the GST implication that would be the deciding factor for the fantasy gaming industry and not legality, since it's a game of skill,” he says. As things stand, though, that last bit sounds like an ambitious bet. Openness and regulation may be virtues on their own, but the law can never be prejudged.

By Jyotika Sood with Qaiser Mohammad Ali