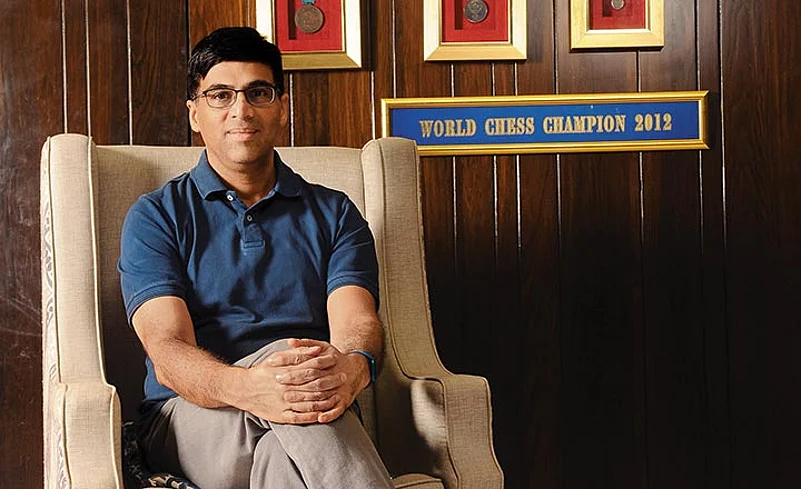

In individual sport, Viswanathan Anand is probably India’s greatest; the grandmaster has gone where no Indian has ever been before. In his book Mind Master: Winning Lessons from a Champion’s Life—part autobiography, part about the lessons he has learnt from chess—the five-time World Champion unveils his battles over 64 squares. In this interview to G.C. Shekhar he discusses the book, his game, being the nice guy and the future of Indian chess.

A memoir or autobiography usually happens when one hangs up the boots. You are still an active player, ranked in the top ten. Why did you write it at this stage in your career?

My 50th birthday (on December 11) provided a convenient timeline. The project has been around for some time. Since the book is about my life lessons it doesn’t matter if I choose to play a few years more.

Is it easier for a chess player to discuss tactics, preparations and post-match analysis and draw wisdom from them than, say, a tennis player? Many of your conclusions can actually be applied in company board rooms or in management courses or simply in real-life situations?

I have done a fair amount of public speaking; it flows from that also. Certainly, chess teaches you lessons that you relate to, especially in the context of learning and artificial intelligence.

Do chess players need to keep reinventing themselves since their last game is recorded, analysed and stored for future reference? Like when you surprised Kramnik with a Queen Pawn opening in Bonn?

Whether you take your existing repertoire and tweak it or you take a radically new area—both happen all the time. You cannot always have a new repertoire for every tournament and you try something new. So in chess you go back and forth.

Elizbar Ubilava (Anand’s trainer) urged that you have to go beyond being India’s and Asia’s first and pursue the World Championship. Any tennis player would want to win the Grand Slam. Your book says you did not have the thrust. Did you lack that fire early on?

No, but my way of thinking about it was innocent. I thought that the World Championship is the end of a long road and if you keep travelling by that road you will reach eventually. What my seconds tried to impress upon me was that you need to think about it more actively. I would have qualified through one of the cycles but my seconds told me the world title is a very hard, steep climb and you need to think in a different way.

You were denied concessions given to your opponents like Karpov and Kasparov by the establishment. Yet you chose not to whine and attribute this to your propensity to stay away from conflict. You even overheard Karpov saying that you will always be the nice guy of chess but did not have the character for a big win. Do you think you could have been a more assertive personality? Or is it your south Indian upbringing that came in the way?

Yes I tend to be a certain kind of person. I hesitated in demanding too much as I will be putting unnecessary pressure on myself. You make a lot of demands and if you play badly you end up with an egg on your face. In Prague, when they were trying to unify the two cycles, I did not have an obvious place in the last four or eight. I could have argued and placed my demands only to be ignored. Or you ignore them and see it as justice, since I had played badly for six months. If I play well there has to be a seat for me at the table. Accepting whatever happens is either mature or you are putting a lot of pain on yourself. Even if Karpov had no chance of winning a tournament he would still make demands, act like a prima donna. I envy that also, but I am comfortable in a certain way of dealing with things.

You say that computers and AI have reduced the geographical advantage that players from Soviet-Russia and Eastern Europe used to enjoy as anyone can access chess data. And they have dented the human ego in chess players. You also observe that in spite of the surfeit of data one often has to play by instinct and improvise. Will a day come when computers will determine how chess will evolve? Or are they doing that already?

They are doing that already. I don’t know anyone who is analysing on his own in a sustained way. Already all the new paths and analysis are driven by computers. But it still helps to have a chess community in your town and playing with human opponents.

You being crowned as India’s first GM inspired many youngsters to take up chess; today, we have 65 GMs. In an interview to Outlook in September 2018 you saw at least five prospective World Champions from India. But Praveen Thipsay recently said that after you no Indian GM has managed to breach the top 20 ranking. Who do you see as champion candidates from India?

If you take the current crop of young players they not only have time on their side but have finished their GM titles. It shows their promise. Young talents like Praggnaanandha, Nirav Sarin, Gukesh, Raunak Sadhwani have time. There are others but I rank them less not because of their strength but because they are in their 20s, which compresses their time frame. Then, Harikirshna was in the top 20 and is still playing a lot of top tournaments. Vidith (Santosh Gujarathi) and Adhipan are doing well. There is tremendous depth.

Even after becoming a GM and you used to be reticent in your media interactions. But Aruna’s arrival appeared to have changed you. You are more articulate, more readily humourous. She is now your manager who decides your scheduling, draws up your contracts and packs your bags. How much of a difference has Aruna made to your chess?

Obviously quite huge. I’ve become very efficient as I am able to do only the chess without being distracted by small things. During the crucial years she was an integral part of the team.

You end the book on a slight note of despondency on how you and Gelfand, both in their 50s now, find youngsters like Carlsen, Aronian and Nakamura too much to handle. Hereafter, is it only about the joy of playing than the pursuit of ranking that will keep you going till you retire officially? Or would you like to spend more time with your son Akhil, not wanting to miss out on his growing up years?

There is no despondency. I am simply talking about reality. I’ve had a full career. You constantly reassess your goals. And chess never comes in conflict with the time I spend with my family. On one hand I disappear for long stretches but when I am here I am fully here. I try to do both. Look, age is a factor and you cannot ignore it.