For banned Indian cricketers, the wheel of destiny has turned a full circle, which will enable them to join the mainstream sport. Since 2000, when the Hansie Cronje match-fixing scandal broke out and led to the BCCI banning four players following a CBI report, a total of 15 players have been banned for various periods for their alleged involvement in three different match or spot-fixing-related episodes. Out of these, ten have either completed punishment periods or their bans have been quashed by courts of law. Recently, the Kerala High Court quashed the life ban on former India fast bowler Sree Santh, who is now 34. He thus joined Mohammed Azharuddin (life ban), Ajay Sharma (life ban) and Ajay Jadeja (five-year ban), who have all won court battles against the BCCI after being banned in 2000.

Sree Santh claims he is “perhaps” fitter than ever, but wants to play first-class cricket for a couple of seasons for Kerala and maybe represent India again. “I just wanted to clear my name. My contention is that I was never involved; I was framed. I am still waiting for BCCI’s permission to start playing. The BCCI and CoA have not been acknowledging my emails; they haven’t even responded to the Kerala Cricket Association’s emails, which is really bad. But I’ve to be patient. If I could wait for four years, I could wait for maybe a couple of months more,” Sree Santh tells Outlook.

But Ravi Sawani, a former top cop and the only man common in all three Indian fixing scandals, feels the prosecution botched up the case and that the acquittal was shocking. “All these were procedural matters in which these players were acquitted. Who is to be blamed? You deduce it from the facts of the matter. Not one of these (court) cases has been decided on weighing the evidence. All have been decided on sheer technicalities. There are any number of Supreme Court judgements which say that a mere technicality should not overthrow the evidence,” Sawani, 66, tells Outlook. As CBI joint director, Sawani wrote the historic match-fixing report in 2000 and after retirement was appointed by the BCCI as a one-man commission to inquire into the 2012 and 2013 fixing events. Later, he was the director of the BCCI’s Anti-Corruption Unit. The BCCI will appeal against the verdict in the Sree Santh case.

Currently, only one player, 32-year-old Mumbai batsman Hiken Shah, who was banned for five years in the 2013 IPL spot-fixing scandal, is in the process of moving the Bombay High Court after his initial petition in 2015 was rejected by the same court. However, former Uttar Pradesh pacer Shalabh Srivastava, now 35, and banned for five years following an India TV sting in 2012, tried in vain to have his punishment rescinded by the Lucknow Bench of the Allahabad High Court.

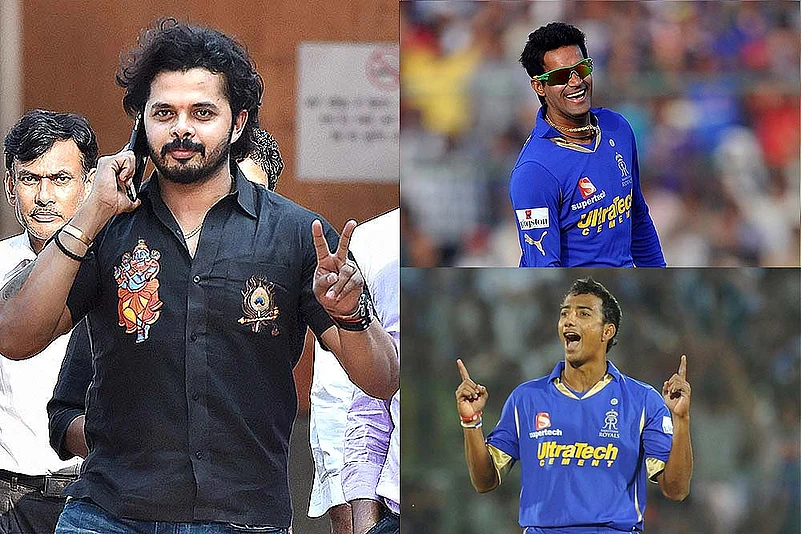

Now, the Sree Santh verdict may encourage other banned cricketers to knock at the door of a court in the hope of clearing their names. Players like T.P. Sudhindra, who was banned for life for allegedly “receiving a consideration to spot-fix in a domestic match” in 2012, and Ajit Chandila, who was banned for life and 33-year-old Amit Singh (banned for five years), both of whom were allegedly involved in the 2013 IPL scandal, may have renewed hope.

Ajay Jadeja, 46, was the first to get a favourable verdict from a court through a court-appointed arbitrator. Then, Azharuddin was reprieved by the Andhra Pardesh High Court and based on his verdict a local court in Delhi overturned the life ban on Ajay Sharma. Interestingly, all three cases, which emanated from the Cronje fixing scandal, were decided on technicalities. They successfully contended that the BCCI constitution did not have any provision to appoint an inquiry commission from outside the Board. Thus, the courts ruled that the appointment of former CBI Joint Director K. Madhavan was illegal, and so was his report, on the basis of which a BCCI disciplinary committee had banned them.

Ajay Jadeja, Azharuddin, Ajay Sharma and Manoj Prabhakar

India all-rounder Manoj Prabhakar, who was also banned for five years along with the then Indian team physiotherapist Ali Irani in 2000, chose not to appeal and returned to the official fold on completion of his term. But Sudhindra wants to appeal to the BCCI for a relook. “I want to write to the BCCI.... I don’t have the dream of playing top-class, my only desire is to play local and club cricket and share my experience with youngsters. It’s not a question of whether I want to clear my name or not. They should analyse my performance since this episode happened and judge me on that and also decide whether I deserve to be in the position I am at the moment,” says Sudhindra, a former Deccan Chargers player. Sree Santh, of course, has greater plans. “I can at the most play two seasons of first-class cricket and maybe help KCA win the Irani Trophy or the Ranji Trophy. On that performance, maybe I can play one or two series for the national team,” he says. In anticipation, he has put his film career on hold. “I’ve given dates to a couple of movies and I am keeping everything on hold, expecting them (BCCI) to call me....”

The Sree Santh verdict has rekindled hope in Chavan, a former Mumbai left-arm spinner. He has been keeping a low profile and didn’t react to media questions on Sree Santh’s reprieve. The 31-year-old spinner, however, spoke to Outlook: “I am waiting for an opportunity and I am quite hopeful of the BCCI reconsidering my situation and allowing me to play.” Chandila, now 33, is also keen to return to competitive cricket some day. The former Rajasthan Royals off-spinner is practising at his home ground, Nahar Singh Stadium in Faridabad, to remain in touch with the game, even though he is not part of his employer’s team, Air India. “I want to stage a comeback. Otherwise, why would I continue to practise?” he asks. Meanwhile, former Gujarat pacer Amit Singh, who was handed a five-year punishment in the IPL episode in 2013 (his ban ends this September), seems to have moved on. He now regularly appears on Gujarati TV channels as a cricket expert.

All those banned in the 2013 IPL scandal, quite predictably, say they were wrongly punished for a crime they weren’t part of and were not given a proper hearing by the inquiry commissioner as well as the BCCI disciplinary committee. One of the players also confessed that it is the worst life for a cricketer. “By offering a few rupees, they have spoiled the lives of several cricketers. Those who’ve not gone through the turbulent phase we are going through can’t imagine what impact it has had on us cricketers. I still can’t get proper sleep at night,” he says about the sting operation by a TV channel which purportedly showed them lured with offers of money for underperformance.

And Azhar and Ajay Sharma are trying to join the mainstream. The BCCI has been inviting Azhar to its various functions. Azhar recently wrote to the Supreme Court-appointed Committee of Administrators (CoA) as well as the BCCI office-bearers to seek his long-pending dues. “The CoA handed his letter over to the BCCI office-bearers to take a call on it. The legal opinion is that it is okay (to give his rightful dues); the BCCI lawyers had no problem with that,” says a source close to the CoA. The committee apparently has received several representations from banned players, including Ajay Sharma, who has applied for a coach’s post with the Delhi and District Cricket Association (DDCA). “The DDCA wants a clearance certificate from BCCI (to accept him back). The CoA will go by the legal view,” says an insider.

With opinion sharply divided on malpractices in cricket, the last word is yet to be said in this highly explosive, unsavoury aspect of the sport. But no can refute the historic fact that with the increase in money in cricket, particularly with the advent of the IPL in 2008, occurrences of players’ misconduct have increased manifold. And, surely, in the footsteps of Sree Santh, there would be several run-ups leading to the highest courts of the land.